The world of insects is vast and fascinating, with over a million described species and potentially millions more awaiting discovery. These tiny creatures, despite their size, play crucial roles in our ecosystems as pollinators, decomposers, pest controllers, and food sources for other animals. Behind the scientific understanding of these remarkable invertebrates are entomologists – dedicated scientists who devote their careers to studying insects in all their six-legged glory. Becoming an entomologist is not merely a career choice but a journey of passion, curiosity, and scientific rigor. This article explores what it takes to enter this specialized field, from educational requirements to personal qualities, and the diverse career paths available to those fascinated by the world’s most abundant animal group.

The Foundation: Developing Early Curiosity

Many entomologists trace their professional journeys back to childhood fascinations with the natural world. This early connection often begins with simple observations – watching ants build colonies, collecting colorful butterflies, or examining the intricate patterns of a spider’s web. Parents and educators who encourage this curiosity rather than dismissing it as a passing phase play crucial roles in nurturing future scientists. Unlike many scientific disciplines that seem remote from daily life, entomology offers accessible entry points through backyard exploration and citizen science projects. The habit of observation, questioning, and seeking answers about the insect world forms the foundation upon which later specialized knowledge can be built. These early experiences often create the emotional connection that sustains entomologists through the challenges of education and research.

Educational Pathways to Entomology

Formal education in entomology typically begins with a bachelor’s degree in biology, zoology, ecology, or agricultural science, with specialized courses in entomology. Many universities offer specific entomology programs at the undergraduate level, though these are less common than broader biology programs with entomological components. Core coursework includes general biology, chemistry, genetics, ecology, and statistics, alongside specialized classes in insect taxonomy, physiology, behavior, and economic entomology. Laboratory and field components are essential aspects of this education, providing hands-on experience with collection techniques, specimen preparation, and experimental design. Advanced positions in research, academia, and specialized industry roles typically require master’s or doctoral degrees focusing specifically on entomological research. Throughout this educational journey, mentorship from established entomologists becomes invaluable for navigating both academic requirements and professional opportunities.

Technical Skills: The Entomologist’s Toolkit

Successful entomologists develop a diverse set of technical skills that extend beyond pure biological knowledge. Fieldwork requires proficiency in collection methods ranging from sweep nets and light traps to more sophisticated environmental DNA sampling techniques. Laboratory analysis demands skills in microscopy, dissection, and taxonomic identification using dichotomous keys and comparative morphology. Modern entomologists increasingly need computational abilities for statistical analysis, ecological modeling, and genetic sequence interpretation. Photography has become an essential skill for documenting specimens and behaviors, while technical writing enables the communication of findings through journal publications and reports. These skills aren’t typically mastered during formal education alone – they develop through practical experience, workshops, field courses, and continuous learning throughout one’s career. The most versatile entomologists maintain a growth mindset, regularly updating their toolkit as methodologies evolve.

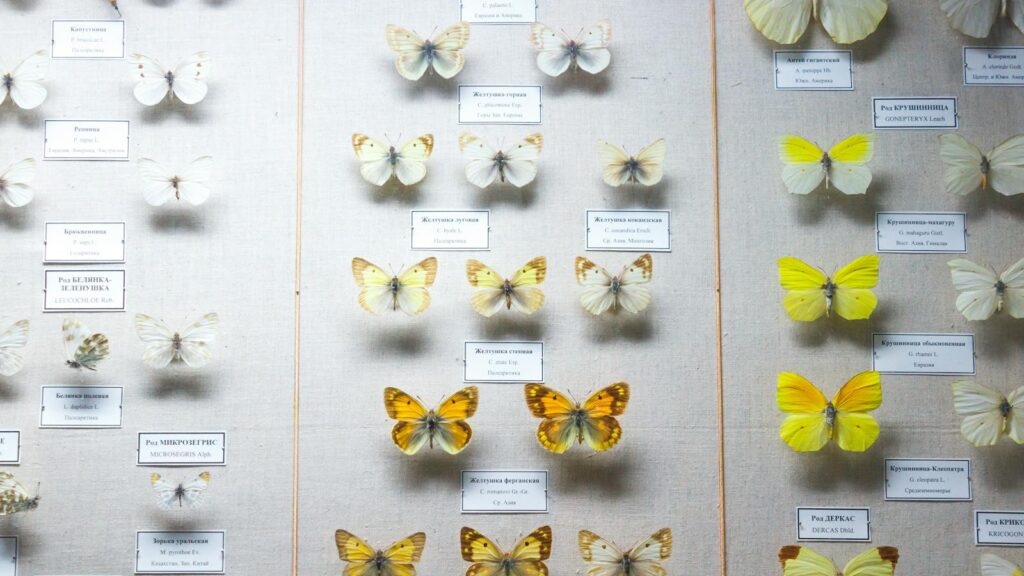

Developing Taxonomic Expertise

Taxonomy – the science of describing, naming, and classifying organisms – remains a cornerstone of entomological practice despite technological advances. Developing taxonomic expertise requires exceptional attention to detail, patience, and a methodical approach to identifying subtle morphological differences between species. This expertise typically focuses on specific insect orders or families, as mastering identification across all insects would be virtually impossible given their diversity. Learning taxonomy involves extensive time with reference collections, dichotomous keys, and increasingly, DNA-based identification methods. Many entomologists apprentice with established taxonomists to learn the nuances of their specialty group’s identification. While modern methods like DNA barcoding supplement traditional approaches, the ability to visually identify insects in the field remains invaluable, especially in regions where technological resources are limited. Taxonomic expertise also contributes to the description of new species – an ongoing process with thousands of insects awaiting formal scientific description.

Field Experience: Beyond the Laboratory

Entomological fieldwork presents unique challenges and rewards that shape a scientist’s perspective and capabilities. This aspect of the profession requires physical stamina for long hours in challenging environments, from tropical rainforests to agricultural fields and urban settings. Field entomologists develop specialized skills in habitat assessment, sampling design, data collection under variable conditions, and adaptability when faced with unexpected circumstances. The ability to think creatively when equipment fails or conditions change unexpectedly distinguishes successful field researchers. Beyond technical aspects, fieldwork builds cultural competence when working in international settings, where collaboration with local experts and communities becomes essential for research success. These experiences often yield the most significant insights into insect behavior and ecology, revealing patterns that laboratory studies alone might miss. For many entomologists, these field experiences – despite discomforts like insect bites, extreme weather, and primitive accommodations – provide the most memorable and meaningful aspects of their professional lives.

Personal Qualities of Successful Entomologists

Beyond academic knowledge and technical skills, certain personal qualities distinguish successful entomologists. Exceptional patience serves researchers well, whether waiting hours to observe a rare behavior or sorting through thousands of trap specimens to find species of interest. Attention to detail allows entomologists to notice subtle morphological differences or behavioral patterns that might otherwise go unrecorded. Resilience helps overcome research setbacks, failed experiments, and the challenges of securing funding in a competitive scientific landscape. Perhaps most importantly, successful entomologists maintain a genuine passion for insects that sustains their motivation through difficult aspects of the profession. This authentic curiosity leads to asking the most innovative questions and pursuing answers with persistence despite obstacles. Additionally, comfort with the occasional social stigma associated with studying “creepy crawlies” helps entomologists become effective ambassadors for their research subjects, turning public fear or disgust into interest and appreciation.

Specializations Within Entomology

Entomology encompasses numerous specialized fields, each offering distinct career trajectories and research opportunities. Agricultural entomologists focus on pest management, pollination, and crop protection, working closely with farmers and the agricultural industry to develop sustainable practices. Medical entomologists study insects that transmit diseases like malaria, dengue fever, and Lyme disease, contributing to public health interventions worldwide. Forensic entomologists apply their knowledge of insect succession on decomposing remains to assist criminal investigations and determine time since death. Conservation entomologists work to protect endangered insect species and their habitats, recognizing their ecological importance beyond human utility. Other specializations include urban entomology (dealing with structural pests), veterinary entomology (focusing on livestock pests), and ecological entomology (studying insects’ roles in ecosystems). These specializations often develop during graduate studies or early career positions when entomologists discover which aspects of the field most align with their interests and strengths.

Career Paths and Employment Opportunities

Entomologists find employment across diverse sectors, with opportunities extending far beyond academia. Universities offer positions in teaching and research, combining the rewards of mentoring students with pursuing original research questions. Government agencies employ entomologists in agricultural departments, public health services, forest services, and regulatory bodies concerned with invasive species. The private sector provides opportunities with pest control companies, agricultural biotechnology firms, pharmaceutical companies researching insect-derived compounds, and environmental consulting firms. Museums and botanical gardens hire entomologists as curators and public educators, helping bridge the gap between scientific research and public understanding. Non-governmental organizations focused on conservation, sustainable agriculture, or international development also value entomological expertise for their programs. The field’s versatility allows practitioners to shift between sectors throughout their careers, following personal interests or responding to emerging opportunities. Entrepreneurial entomologists sometimes establish their own consulting businesses or educational ventures, creating unique career paths that combine scientific expertise with business acumen.

The Importance of Scientific Communication

Effective communication stands as a crucial skill for entomologists seeking to make their research impactful. Scientific writing for peer-reviewed journals requires precision, clarity, and adherence to disciplinary conventions – skills developed through practice and mentorship. Equally important is the ability to translate complex findings for non-specialist audiences, from farmers implementing integrated pest management to policymakers making decisions about vector control programs. Public communication through outreach events, social media, and popular science writing helps combat widespread entomophobia (fear of insects) and builds appreciation for these often-misunderstood animals. Visual communication through photography, illustration, and data visualization enhances both scientific publications and public engagement. Entomologists who excel at communication often find their research has greater reach and practical impact, while also enjoying broader career opportunities in education, science writing, and advisory roles. The field increasingly recognizes that scientific discovery alone is insufficient without effective dissemination to relevant audiences.

Networking and Professional Development

Building professional connections forms an essential aspect of an entomological career that extends beyond formal education. Professional societies like the Entomological Society of America, the Royal Entomological Society, and numerous regional or specialized organizations provide platforms for networking through conferences, publications, and committee work. These connections facilitate collaborations, job opportunities, and mentoring relationships that shape career trajectories. Attending conferences, though sometimes financially challenging for early-career entomologists, offers irreplaceable opportunities to present research, receive feedback, and forge connections with potential employers or collaborators. Online communities have expanded networking possibilities, with platforms like Twitter, ResearchGate, and specialized forums enabling global connections around specific research interests. Professional development continues throughout an entomologist’s career through workshops, certifications, and continuing education opportunities that introduce new methodologies and research areas. The most successful practitioners actively contribute to these professional communities rather than merely benefiting from them, strengthening the discipline through mentorship, peer review, and organizational service.

Challenges in the Field

Aspiring entomologists should understand the challenges that accompany this rewarding profession. Funding constraints present ongoing obstacles, particularly for basic research without immediate economic applications, requiring persistence in grant writing and creative approaches to resource acquisition. Field conditions can be physically demanding, with exposure to disease vectors, extreme climates, and remote locations without modern amenities. The specialized nature of entomological knowledge sometimes leads to professional isolation, especially for those working as the sole insect specialist within broader teams or institutions. Career advancement may progress more slowly than in higher-profile scientific fields, with fewer positions available at senior levels. The emotional challenge of witnessing insect population declines and habitat destruction affects many conservation-minded entomologists, creating a sense of urgency in their work. Despite these challenges, most practitioners report high job satisfaction stemming from the intellectual stimulation, practical impact, and connection to nature their profession provides. Understanding these realities helps prospective entomologists develop realistic expectations while preparing strategies to navigate the field’s difficulties.

The Global Dimension: International Opportunities

Entomology offers exceptional opportunities for international work and collaboration due to insects’ global distribution and their involvement in worldwide challenges from food security to disease transmission. Field research frequently takes entomologists to biodiversity hotspots in tropical regions, where insect diversity reaches its peak but scientific capacity may be limited. International development organizations employ entomologists for agricultural improvement and public health programs in developing nations, combining scientific expertise with cross-cultural competence. Collaborative research increasingly spans borders, with specialists in taxonomy, genetics, behavior, and applied entomology forming international teams to address complex questions. The importation of invasive pest species has created demand for regulatory entomologists working at borders and in international trade oversight. These global dimensions require adaptability, cultural sensitivity, and often language skills beyond scientific knowledge. For many entomologists, these international connections become defining aspects of their careers, providing perspective on both the universality of ecological principles and the diversity of approaches to entomological challenges across cultures.

The Future of Entomology

The field of entomology continues to evolve, with emerging technologies and changing global conditions creating new research frontiers and career opportunities. Genomic approaches are revolutionizing understanding of insect evolution, adaptation, and potential for genetic modifications addressing agricultural and public health challenges. Climate change research increasingly incorporates entomological perspectives, as insects serve as sensitive indicators of environmental shifts and play crucial roles in ecosystem responses. The alarming decline in insect biomass worldwide has created urgency around conservation entomology, with opportunities for those developing monitoring methods and protection strategies. Technological innovations like remote sensing, automated monitoring systems, and artificial intelligence for species identification are creating new specializations at the intersection of entomology and data science. Urban entomology grows increasingly important as human populations concentrate in cities, bringing challenges in pest management and opportunities for designed urban ecosystems supporting beneficial insects. These emerging directions suggest that tomorrow’s entomologists will require interdisciplinary skills combining traditional knowledge with technological fluency and systems thinking, adapting a centuries-old discipline to address contemporary challenges.