Right now, as you read this, millions of tiny stowaways are crossing international borders without passports. They’re traveling in Christmas trees, camping gear, and even your favorite houseplant. These microscopic migrants aren’t tourists—they’re biological invaders reshaping ecosystems one branch at a time.

The global trade of wood products, live plants, and everyday packaging materials has created an invisible superhighway for insects. Every shipment carries potential ecological chaos wrapped in innocent-looking bark, leaves, and cardboard. What seems like harmless commerce is actually facilitating one of the most devastating environmental disasters of our time.

The Wooden Trojan Horse: Firewood as an Insect Highway

Firewood might look like simple fuel for your campfire, but it’s actually one of nature’s most effective insect transportation systems. Dead wood provides the perfect hiding spots for beetle larvae, moth pupae, and countless other species that can remain dormant for months.

When you transport firewood from one location to another, you’re essentially running a free shuttle service for invasive insects. A single log can harbor dozens of different species, from tiny bark beetles to large wood-boring moths. The emerald ash borer, responsible for killing millions of ash trees across North America, spread primarily through contaminated firewood moved by unsuspecting campers.

Many insects in their larval stage are nearly impossible to detect with the naked eye. They burrow deep into the wood grain, creating tunnels that won’t be visible until they emerge as adults. By then, it’s often too late—they’ve already established themselves in their new environment.

Plant Nurseries: The Unintended Insect Breeding Grounds

Commercial plant nurseries inadvertently serve as insect airports, with potted plants acting as first-class tickets to new territories. The warm, humid conditions in greenhouses create perfect breeding environments for many pest species.

Aphids, scale insects, and whiteflies are particularly adept at hitchhiking on ornamental plants. These tiny creatures can reproduce rapidly once they reach their destination, often going unnoticed until they’ve established massive colonies. A single infected plant can introduce thousands of insects to a new ecosystem within weeks.

The global houseplant boom has accelerated this problem significantly. Social media’s plant influencer culture has created unprecedented demand for exotic species, leading to increased imports from countries with different pest populations. That trendy monstera or rare orchid might be carrying microscopic passengers that could devastate local agriculture.

Packaging Materials: The Invisible Vectors

Cardboard boxes, wooden crates, and plastic containers might seem sterile, but they’re surprisingly effective at harboring insect life. Many species lay eggs in the tiny crevices and folds of packaging materials, where they can survive long international journeys.

The brown marmorated stink bug has become infamous for its ability to hide in shipping containers. These insects can survive for months without food, emerging in spring to wreak havoc on crops and gardens. They’ve spread from Asia to every continent except Antarctica, largely through contaminated packaging.

Even seemingly clean packaging materials can harbor insects. Fruit flies can lay eggs in microscopic food residues, while carpet beetles thrive in the organic materials used in some packaging. The sheer volume of global trade means that even a tiny contamination rate can result in millions of invasive insects being transported daily.

The Speed of Modern Invasion

Modern transportation has compressed what used to be evolutionary timescales into mere decades. Insects that would have taken centuries to spread naturally can now colonize new continents in a matter of days.

Air cargo is particularly problematic because it maintains relatively stable temperatures and humidity levels that many insects find comfortable. A flight from Southeast Asia to North America takes less than 24 hours—not enough time for most insects to die from environmental stress, but plenty of time to cross natural barriers like oceans and mountain ranges.

The frequency of modern shipping has also increased the likelihood of successful invasions. Multiple introductions of the same species from different source populations increase genetic diversity and the chances of establishing viable breeding populations.

Climate Change: The Perfect Storm

Rising global temperatures are making previously inhospitable regions suitable for invasive insects. Species that were once limited by cold winters can now survive in areas that were previously too harsh for them.

The mountain pine beetle, native to western North America, has expanded its range northward as winter temperatures have moderated. Millions of acres of forest have been destroyed as these beetles encounter naive tree populations with no natural defenses.

Climate change also affects the timing of insect life cycles, potentially disrupting the synchronization between insects and their natural predators or parasites. This can give invasive species a competitive advantage in their new environments.

Agricultural Apocalypse: When Bugs Meet Crops

The agricultural impact of insect invasions is staggering, with billions of dollars in crop damage occurring annually. Many of our most important food crops evolved in isolation from the insects that now threaten them.

The Asian citrus psyllid, which spreads a devastating bacterial disease called huanglongbing, has decimated citrus industries worldwide. Florida’s orange production has dropped by over 70% since the insect’s arrival, and entire groves have been abandoned.

Some invasive insects don’t just eat crops—they fundamentally alter agricultural ecosystems. The varroa mite, which parasitizes honeybees, has contributed to colony collapse disorder and threatens global food security through pollination disruption.

Forest Ecosystems Under Siege

Forests represent some of the most complex and vulnerable ecosystems on Earth, making them particularly susceptible to invasive insect damage. Many tree species have evolved specific defenses against local insect populations but are helpless against foreign invaders.

The emerald ash borer has eliminated ash trees from vast swaths of North American forests, fundamentally altering forest composition and wildlife habitat. The speed of this destruction—entire forest stands can be killed within a few years—gives ecosystems no time to adapt.

Invasive insects can also disrupt forest food webs in unexpected ways. When they eliminate key tree species, they affect everything from soil chemistry to bird populations, creating cascading effects throughout the entire ecosystem.

Urban Jungles: Cities as Invasion Launching Pads

Cities serve as both entry points and launching pads for invasive insects. Urban environments often lack the natural predators and parasites that might control invasive species, allowing them to build up large populations before spreading to surrounding areas.

The heat island effect in cities can create microclimates that favor certain invasive insects, particularly those from tropical regions. Urban areas also provide diverse food sources and shelter opportunities that can support insects that might struggle in natural environments.

Many invasive insects actually prefer urban environments to their native habitats. The abundance of ornamental plants, reduced pesticide use in residential areas, and lack of natural enemies can make cities more hospitable than their original homes.

The Hidden Costs of Biological Invasion

The economic impact of invasive insects extends far beyond direct agricultural damage. Treatment costs, quarantine measures, and lost ecosystem services add up to hundreds of billions of dollars annually worldwide.

Property values can plummet when invasive insects attack urban forests. The loss of mature trees not only affects aesthetics but also reduces energy efficiency, air quality, and overall livability of neighborhoods.

The psychological impact on communities should not be underestimated. Watching familiar landscapes transformed by invasive insects can create feelings of helplessness and environmental grief that affect mental health and community cohesion.

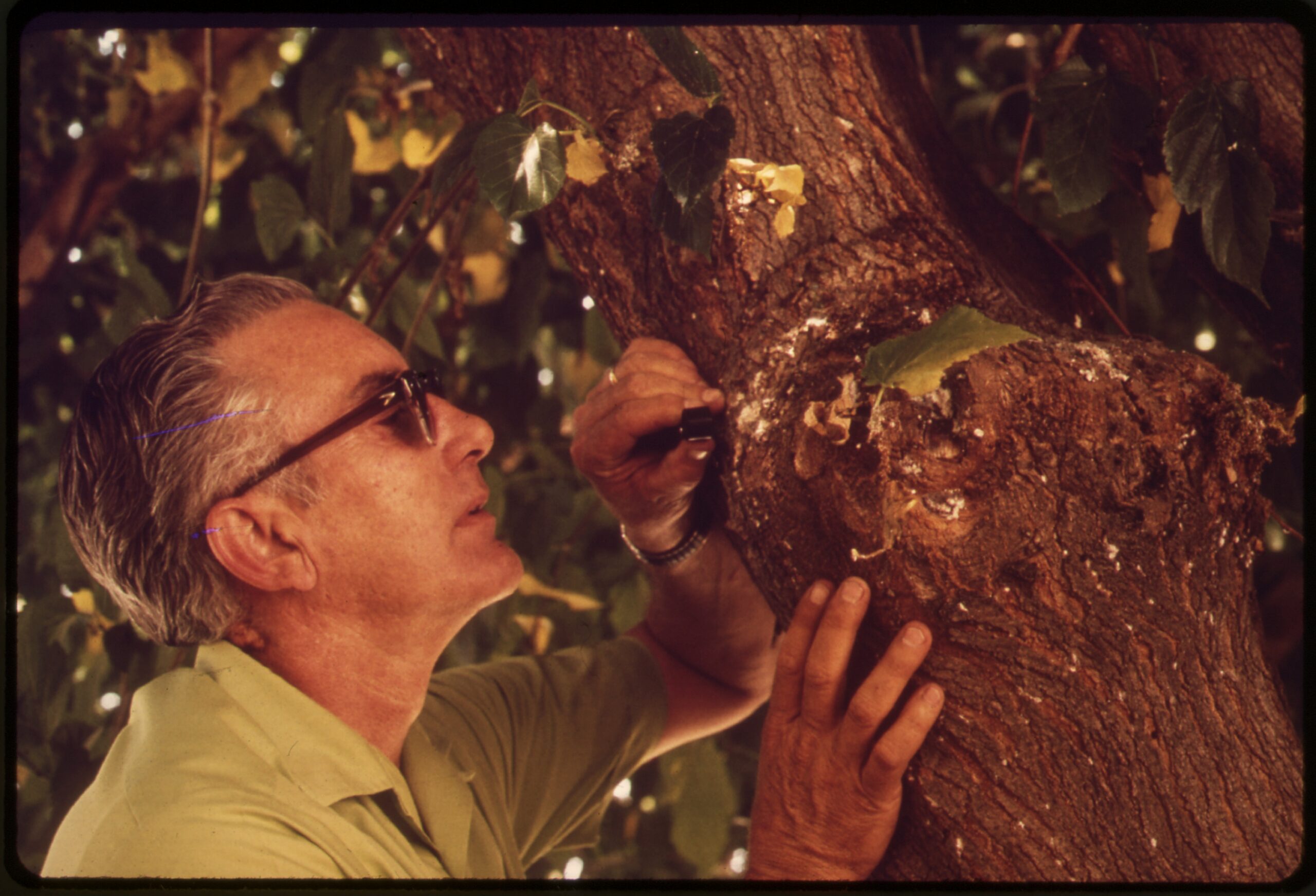

Detection Challenges: Finding Needles in Haystacks

Early detection of invasive insects is crucial for successful control, but it’s extraordinarily difficult. Many species are small, cryptic, or active only at certain times of day or year, making them easy to overlook until populations explode.

Traditional monitoring methods rely on traps baited with pheromones or visual surveys, but these approaches often miss new species or detect them too late for effective intervention. New technologies like environmental DNA sampling and automated insect identification systems show promise but are still in development.

The sheer volume of global trade makes comprehensive inspection impossible. Even if inspectors could examine every shipment, many invasive insects are too small or well-hidden to detect with current methods.

Natural Enemies: The Biological Arms Race

In their native habitats, most insects are kept in check by natural enemies—predators, parasites, and diseases that have evolved alongside them. When insects invade new territories, they often leave these natural controls behind, giving them a massive advantage.

Classical biological control involves importing natural enemies from an insect’s native range, but this approach is risky and slow. Extensive testing is required to ensure that the control agents won’t become invasive themselves or harm non-target species.

Some invasive insects have proven remarkably adaptable, quickly evolving resistance to control measures or finding new ecological niches. This evolutionary flexibility makes them particularly dangerous invaders.

Technology’s Double-Edged Sword

Modern technology has both accelerated insect invasions and provided tools to combat them. GPS tracking can help identify invasion pathways, while genetic analysis can determine the source populations of invasive species.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning are being used to predict which species are most likely to become invasive and where they’re likely to establish. These tools could help authorities focus limited resources on the highest-risk scenarios.

However, technology also facilitates invasions through increased trade volume, faster transportation, and new pathways like online plant sales. The challenge is harnessing technology’s benefits while minimizing its contribution to the problem.

Prevention: The Only Sustainable Solution

Preventing invasions is far more cost-effective than attempting to control established invasive species. Once an invasive insect becomes established, complete eradication is often impossible, and management becomes a permanent, expensive commitment.

International cooperation is essential for effective prevention. Invasive species don’t respect political boundaries, and successful control requires coordinated efforts across countries and continents.

Education and awareness programs can help reduce accidental introductions. When people understand how their actions contribute to invasive species spread, they’re more likely to take preventive measures like buying local firewood or inspecting plants before transport.

The Future of Biological Invasion

Climate change, increasing global trade, and urbanization are likely to accelerate the pace of biological invasions in the coming decades. We’re entering an era where the question isn’t whether new invasive species will arrive, but how quickly we can detect and respond to them.

Genetic technologies like CRISPR might eventually allow us to engineer resistance into vulnerable species or create more effective biological control agents. However, these approaches raise ethical and ecological questions that society is only beginning to address.

The next generation of invasive species may be even more challenging to control. As we develop new control methods, insects continue to evolve, potentially developing resistance to our best management tools.

Those innocent-looking logs in your backyard or the exotic plant on your windowsill might be harboring the next ecological disaster. Every time we move organic materials without proper precautions, we’re playing Russian roulette with entire ecosystems. The question isn’t whether the next major invasion will happen, but where it will strike first and how much damage it will cause before we notice. What seemingly harmless item in your home might be preparing to change the world?