Our beloved pets bring joy, companionship, and unconditional love to our lives. Whether you have a cuddly cat, playful dog, colorful fish, or scaly reptile, creating a clean and healthy environment for them is paramount to their wellbeing. However, lurking in the corners of pet bedding, food bowls, and aquariums are microscopic invaders that often go unnoticed until they cause problems. These hidden bugs—bacteria, fungi, parasites, and other microorganisms—can impact both pet and human health in surprising ways. In this comprehensive article, we’ll explore these invisible inhabitants of our pets’ environments, how they affect our animal companions, and what we can do to keep these spaces cleaner and safer.

The Microscopic World in Pet Environments

Pet environments teem with microbial life invisible to the naked eye. A single square inch of pet bedding can harbor millions of microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, mites, and other microscopic creatures. These microbes aren’t necessarily all harmful—many form part of the natural microbiome that exists in all environments. However, when certain pathogenic species multiply unchecked, they can lead to health issues for both pets and their human families. Research has shown that pets’ living spaces often contain higher concentrations of certain bacteria than other household areas, creating microenvironments with unique ecological characteristics. Understanding this hidden ecosystem is the first step in managing it effectively and ensuring our pets live in spaces that support rather than compromise their health.

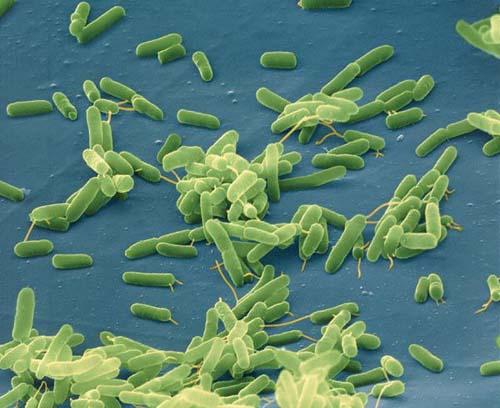

Bacterial Biofilms: The Invisible Fortress

One of the most persistent forms of bacterial contamination in pet environments is the biofilm—a complex community of microorganisms that adhere to surfaces and secrete a protective matrix. In pet food and water bowls, these biofilms can form within 24-48 hours, creating a slimy layer that protects bacteria from cleaning agents and allows them to proliferate. Studies have found that pet bowls often harbor concerning bacteria including E. coli, Salmonella, and Staphylococcus, with plastic bowls typically accumulating more bacteria than stainless steel or ceramic alternatives. What makes biofilms particularly problematic is their resistance to casual cleaning—simply rinsing a bowl with water does little to disrupt these established bacterial communities. Even more concerning, bacteria within biofilms can exchange genetic material, potentially sharing antibiotic resistance genes and becoming increasingly difficult to eliminate.

Bedding Bugs: What’s Living in Your Pet’s Sleeping Area

Pet bedding creates an ideal environment for microbial growth due to the combination of warmth, moisture, skin cells, and hair that accumulate there. Dogs and cats shed approximately 1-2 billion skin cells daily, providing ample food for dust mites and bacteria. These microscopic arachnids feed on the dead skin cells and can trigger allergic reactions in both pets and humans. Beyond dust mites, pet beds frequently harbor fungi like Malassezia, which can cause skin infections, and bacteria that contribute to odors and potential health issues. Even clean-looking bedding can contain significant microbial populations, as a study from North Carolina State University discovered that newly washed dog beds reaccumulated bacteria to pre-washing levels within just four days. This rapid colonization demonstrates why regular, thorough cleaning of pet bedding is essential rather than optional.

Aquarium Ecosystems: Balance and Disruption

Aquariums represent complex microbiological ecosystems where balance is crucial for fish health. The nitrogen cycle in aquariums depends on beneficial bacteria that convert toxic ammonia from fish waste into less harmful nitrates. However, this delicate system can be disrupted by harmful bacteria and parasites that thrive in poorly maintained tanks. Common problems include Ichthyophthirius multifiliis (white spot disease), which appears as white cysts on fish, and various fungi that manifest as cotton-like growths on fish or tank surfaces. Bacterial infections can spread rapidly in enclosed aquatic environments, with organisms like Aeromonas and Pseudomonas causing fin rot and other serious conditions in fish. Research has shown that maintaining appropriate water parameters and cleaning practices doesn’t eliminate microorganisms but rather fosters beneficial populations while limiting pathogenic ones—highlighting the importance of management rather than sterilization in aquatic environments.

Cross-Contamination: From Pet Areas to Human Spaces

The microorganisms in pet environments don’t always stay confined to those spaces, creating potential vectors for cross-contamination throughout the home. Studies have detected pet-associated bacteria on kitchen counters, bathroom surfaces, and even toothbrushes in homes with pets, demonstrating how easily these microbes can travel. Zoonotic pathogens—those capable of jumping from animals to humans—present particular concern, with organisms like Campylobacter, Salmonella, and certain parasites potentially causing illness in humans after contact with contaminated pet areas. Research from the CDC indicates that approximately 6 out of 10 infectious diseases in humans can be spread from animals, highlighting the importance of hygiene at the human-animal interface. This transmission doesn’t require direct contact with visibly soiled areas—even microscopic particles transferred by touch or airborne spread can carry potentially harmful microorganisms.

The Danger of Antimicrobial Resistance Development

One concerning aspect of microbial populations in pet environments is their potential role in developing antimicrobial resistance (AMR). When bacteria are repeatedly exposed to cleaning products containing antimicrobial agents at sub-lethal concentrations, they can develop resistance mechanisms that make them harder to eliminate. Studies have identified multiple drug-resistant bacteria in pet food bowls, particularly those cleaned inconsistently or with inappropriate products. This resistance doesn’t just affect the pet environment—these bacteria can potentially transfer resistance genes to other microorganisms, contributing to the broader public health concern of antibiotic resistance. Research published in the Journal of Small Animal Practice found that pets can serve as reservoirs for resistant bacteria and may contribute to the spread of these organisms between animals and humans. This finding emphasizes the importance of effective cleaning practices that eliminate rather than merely suppress bacterial populations.

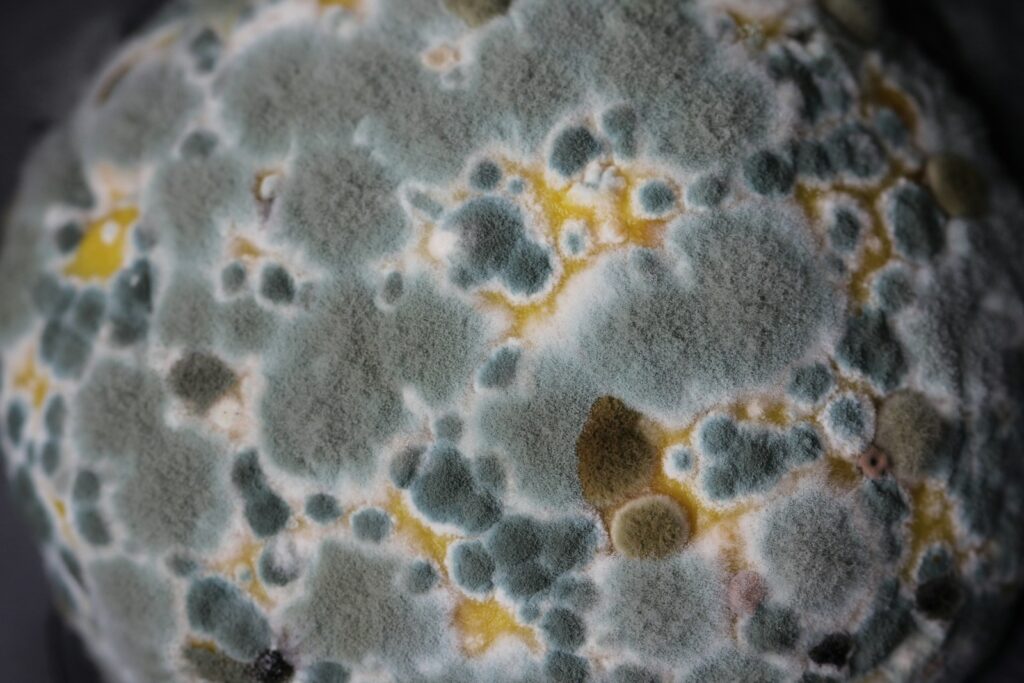

Fungi and Mold: Hidden Allergens in Pet Spaces

Fungal organisms represent another category of hidden bugs that flourish in pet environments, particularly in areas with moisture or limited air circulation. Pet bedding, especially when damp, provides an ideal growth medium for various mold species that produce airborne spores capable of triggering respiratory issues in both pets and humans. Certain fungi like Aspergillus can cause aspergillosis, a serious respiratory infection, while others produce mycotoxins that may have long-term health impacts when exposure is chronic. Dogs and cats with compromised immune systems are particularly vulnerable to fungal infections originating from contaminated bedding or feeding areas. Environmental sampling studies have found that pet areas often contain elevated levels of specific fungi compared to other household locations, with species diversity often reflecting the outdoor environments where pets spend time—demonstrating how pets can introduce outdoor fungi into the home environment.

Parasites: The Hitchhikers in Pet Environments

Beyond bacteria and fungi, various parasites may inhabit pet environments, often introduced through contact with infected animals or contaminated soil. Flea eggs and larvae can thrive in pet bedding, completing their life cycle and leading to reinfestation even after treating the pet directly. Similarly, intestinal parasite eggs from worms like roundworms and hookworms can survive in the environment for months, potentially causing reinfection or zoonotic transmission to humans. More concerning are parasites like Toxoplasma gondii, which can be found in cat environments and poses risks to pregnant women and immunocompromised individuals. Research from the Cornell Feline Health Center indicates that environmental control is as important as direct pet treatment in breaking parasite life cycles, highlighting the importance of thorough cleaning of pet spaces. Regular environmental treatment, combined with veterinary-directed parasite prevention programs, offers the most comprehensive approach to managing these persistent hitchhikers.

Effective Cleaning Strategies for Pet Bedding

Maintaining clean pet bedding requires more than occasional washing—it demands a strategic approach that addresses the invisible microbial populations residing there. For machine-washable beds, veterinary parasitologists recommend washing at temperatures of at least 140°F (60°C) to effectively kill dust mites, bacteria, and many parasite eggs. Adding one cup of white vinegar to the wash cycle can help neutralize odors and has mild antimicrobial properties. For beds that cannot be machine washed, regular vacuuming with a HEPA-filter vacuum removes a significant portion of allergens and parasites, while periodic steam cleaning provides deeper sanitization without harsh chemicals. Beyond cleaning, prevention strategies include using washable covers that can be changed more frequently than the entire bed, selecting beds with antimicrobial fabrics, and placing beds in well-ventilated areas to discourage moisture accumulation. For pets with known skin conditions or allergies, more frequent cleaning cycles and specialized antimicrobial treatments may be recommended by veterinarians.

Best Practices for Food and Water Bowls

Food and water bowls represent primary points of microbial accumulation in pet environments due to their constant exposure to food particles, saliva, and environmental contaminants. Veterinary nutritionists recommend daily washing of food bowls and refreshing water bowls at minimum once daily, with thorough cleaning at least every other day. The most effective cleaning involves scrubbing with hot, soapy water to disrupt biofilms, followed by thorough rinsing and regular disinfection with pet-safe disinfectants or by running dishwasher-safe bowls through a hot cycle. Material selection significantly impacts bacterial accumulation, with stainless steel and ceramic generally harboring fewer bacteria than plastic, which can develop micro-scratches that shelter bacteria from cleaning. Elevated feeding stations may reduce environmental contamination by limiting splashing and containing spills, while automatic water fountains with built-in filtration systems can help maintain cleaner water. For multi-pet households, providing separate feeding stations helps prevent cross-contamination between animals and reduces competition that might lead to rushed eating and increased mess.

Maintaining Healthy Aquarium Microbiology

Aquarium maintenance requires a nuanced approach that preserves beneficial bacterial colonies while preventing overgrowth of pathogenic organisms. Regular partial water changes of 10-25% weekly remove accumulated nitrates and other waste products without disrupting the biological filtration system. Gravel vacuuming during water changes removes organic debris that would otherwise decompose and contribute to poor water quality. Testing water parameters regularly—including ammonia, nitrite, nitrate, and pH levels—provides early warning of biological imbalances before they manifest as visible problems. Avoiding overcrowding and overfeeding represents one of the most effective preventive measures, as excess fish waste and uneaten food quickly degrade water quality and promote harmful bacterial growth. Quarantining new fish before adding them to established tanks prevents introduction of pathogens, while maintaining appropriate temperature and filtration supports the immune function of aquatic pets. Research from aquatic veterinarians indicates that stable, mature aquariums with established beneficial bacterial populations provide the best defense against disease outbreaks.

Natural and Chemical Cleaning Solutions: Finding Balance

When addressing microbial populations in pet environments, pet owners face choices between natural cleaning methods and commercial antimicrobial products. Natural options like vinegar (5% acetic acid), hydrogen peroxide (3% solution), and enzymatic cleaners offer varying degrees of effectiveness against different microorganisms without introducing potentially harmful chemical residues. Studies show that white vinegar can reduce bacterial populations by approximately 90% when used at full strength, though it’s less effective against certain fungi and parasites. Commercial pet-safe disinfectants typically offer broader antimicrobial action but require careful attention to contact times—many products need to remain wet on surfaces for 5-10 minutes to achieve stated efficacy. Environmental toxicologists caution against using products containing phenols, ammonia, or chlorine bleach around pets, particularly cats, who may be sensitive to these chemicals or ingest residues during grooming. Finding balance often means using gentler daily cleaning methods supplemented by periodic deeper disinfection, with product selection guided by the specific health concerns and sensitivities of individual pets.

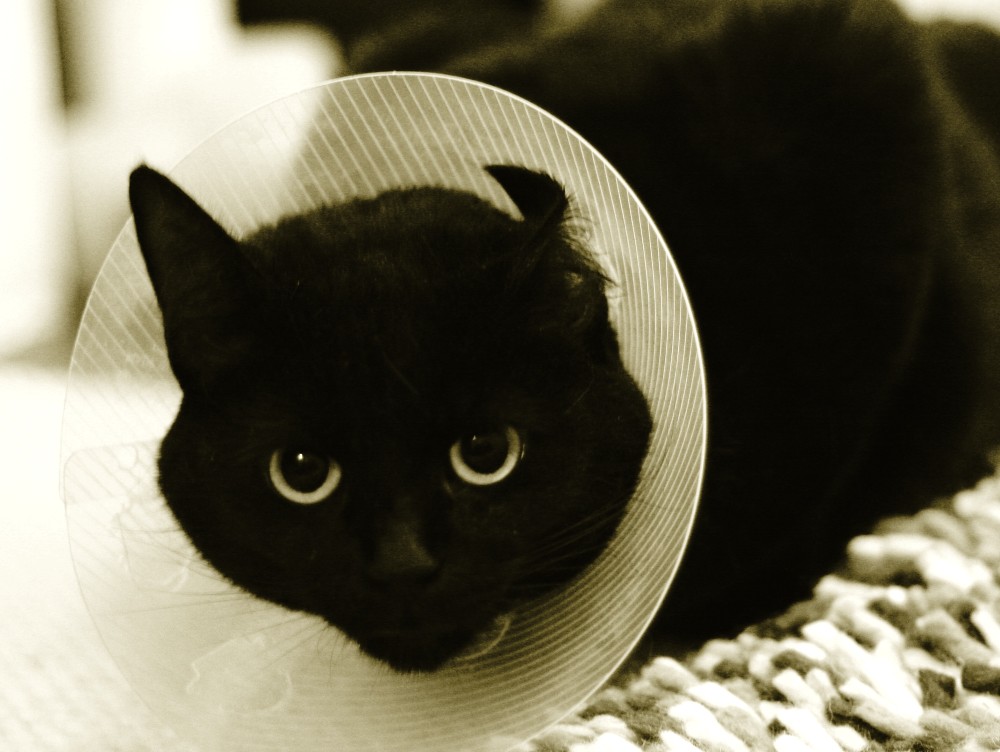

Special Considerations for Pets with Health Conditions

Pets with compromised immune systems, skin conditions, or respiratory issues require enhanced vigilance regarding environmental microorganisms. For immunocompromised pets, veterinary dermatologists recommend more frequent bedding changes, potentially daily for animals undergoing chemotherapy or with severe immune disorders. Pets with allergic skin disease benefit from hypoallergenic bedding materials washed in fragrance-free detergents, while those with respiratory conditions need bedding kept scrupulously free of dust and mold spores. Animals recovering from surgical procedures require particularly clean environments to prevent wound infections, potentially necessitating dedicated bedding that can be easily sanitized. For pets with gastrointestinal parasites, environmental decontamination becomes crucial to prevent reinfection, with specialized cleaning products designed to destroy resistant parasite eggs. Working closely with veterinarians to develop customized cleaning protocols for medically vulnerable pets ensures that environmental management supports rather than hinders treatment efforts, with approaches tailored to specific conditions and sensitivities.

The Future of Pet Environment Management

Emerging technologies and research are changing our understanding of microorganisms in pet environments and offering new solutions for their management. Probiotic cleaners represent one innovative approach, introducing beneficial bacteria that compete with pathogenic species for resources rather than attempting to eliminate all microorganisms. Advanced materials incorporating antimicrobial properties, such as silver-infused fabrics for pet bedding or copper-alloy feeding bowls, provide passive ongoing protection against bacterial accumulation. Environmental monitoring technologies, including consumer-accessible ATP testing systems that detect biological residues, allow pet owners to objectively assess cleaning effectiveness rather than relying on visual inspection alone. Research into the pet microbiome is revealing complex relationships between environmental microorganisms and pet health, suggesting that complete sterilization may be less desirable than fostering diverse, balanced microbial communities. As our understanding evolves, the future likely holds more sophisticated, ecological approaches to managing the hidden bugs in pet environments, focusing on microbial balance rather than elimination.

Conclusion

Creating healthier environments for our pets requires understanding and addressing the invisible microbial world that exists alongside them. From the biofilms in water bowls to the mites in bedding and the delicate bacterial balance in aquariums, these hidden bugs influence pet health in profound ways. By implementing thoughtful cleaning practices, choosing appropriate materials, and understanding the specific needs of different pets and environments, we can better protect both our animal companions and ourselves from potential pathogens while supporting beneficial microbial communities. The goal isn’t a sterile environment but rather a balanced one where harmful organisms are kept in check and beneficial ones can thrive—much like the natural environments our pets’ wild ancestors inhabited. With growing scientific understanding and evolving management approaches, we can create living spaces that support the health and wellbeing of all members of our households, both human and animal.