From the earliest days of cinema, filmmakers have tapped into humanity’s primal fears and fascinations to create memorable monsters. Among these creatures, insect-inspired horrors hold a special place in our collective nightmares. These bug monsters have undergone a remarkable transformation over the decades, evolving from the rubber-suited behemoths of the 1950s to the photorealistic nightmares of modern cinema. This evolution reflects not only advances in filmmaking technology but also shifting cultural anxieties and our complex relationship with the insect world. As we explore this fascinating cinematic journey, we’ll witness how these chitinous creatures have crawled from campy beginnings to become some of the most terrifying monsters to grace our screens.

The Dawn of Bug Cinema: Early Insect Fears

The earliest bug monsters emerged during the silent film era, with movies like “The Centipede” (1920) introducing audiences to oversized arthropods. These primitive effects, often using stop-motion animation and practical models, laid the groundwork for the insect invasion to come. Films of this era reflected the mystery surrounding insects and arachnids, beings that seemed alien despite sharing our world. The 1920s and 1930s saw films like “The Spider” (1931) tapping into arachnophobia, using simple but effective techniques to magnify the inherent creepiness of eight-legged creatures. These early ventures into entomological horror were constrained by technical limitations but compensated with atmospheric lighting and suggestive storytelling that allowed viewers’ imaginations to fill in the terrifying details.

The Atomic Age: Radiation and Giant Bugs

The 1950s ushered in the golden age of giant bug movies, directly reflecting Cold War anxieties and nuclear fears. “Them!” (1954), featuring giant irradiated ants in the New Mexico desert, became the template for dozens of similar films. The premise was simple yet effective: atomic testing had created monstrous versions of already-feared creatures. “Tarantula” (1955), “The Deadly Mantis” (1957), and “The Black Scorpion” (1957) followed this winning formula, presenting enlarged versions of familiar insects wreaking havoc on unsuspecting communities. These films combined genuine scientific information about insects with exaggerated threats, creating a subgenre that balanced educational content with pure entertainment. Despite their sometimes laughable effects by today’s standards, these atomic age bug films tapped into legitimate fears about mankind’s technological overreach and environmental tampering.

Crawling Into the Mainstream: Bugs as Metaphor

By the 1960s and 1970s, bug monsters began to represent more complex societal issues beyond simple atomic fears. Films like “Phase IV” (1974) depicted hyper-intelligent ants engaging in psychological warfare against humans, suggesting themes of collective consciousness and hive minds that challenged human individualism. The British film “The Deadly Bees” (1966) used its insect antagonists as vehicles for exploring themes of isolation and paranoia. During this period, filmmakers began to recognize the narrative potential of insects as metaphors for various social anxieties. Their alien appearance, collective behaviors, and sometimes parasitic relationships with other species made them perfect symbolic vessels for exploring humanity’s place in the natural world. These films marked a transition from pure monster movies to more thoughtful, if still exploitation-heavy, examinations of human-nature relationships.

The Body Horror Revolution: Cronenberg’s Contribution

David Cronenberg’s “The Fly” (1986) represented a watershed moment in bug monster cinema, elevating the genre to new heights of psychological and body horror. This remake of the 1958 film transformed the concept from a simple head-swap story into a devastating examination of physical deterioration and loss of humanity. Jeff Goldblum’s portrayal of Seth Brundle, slowly metamorphosing into a human-fly hybrid, brought unprecedented emotional depth to insect horror. The film’s groundbreaking special effects showed in graphic detail how a human body might transform into something insectoid, creating some of cinema’s most disturbing and memorable imagery. “The Fly” demonstrated that bug monster movies could transcend their B-movie origins to become legitimate vehicles for exploring profound questions about identity, disease, and the fragility of human existence. Cronenberg’s influence would be felt in virtually all serious bug monster films that followed.

Alien Insects: The Extraterrestrial Connection

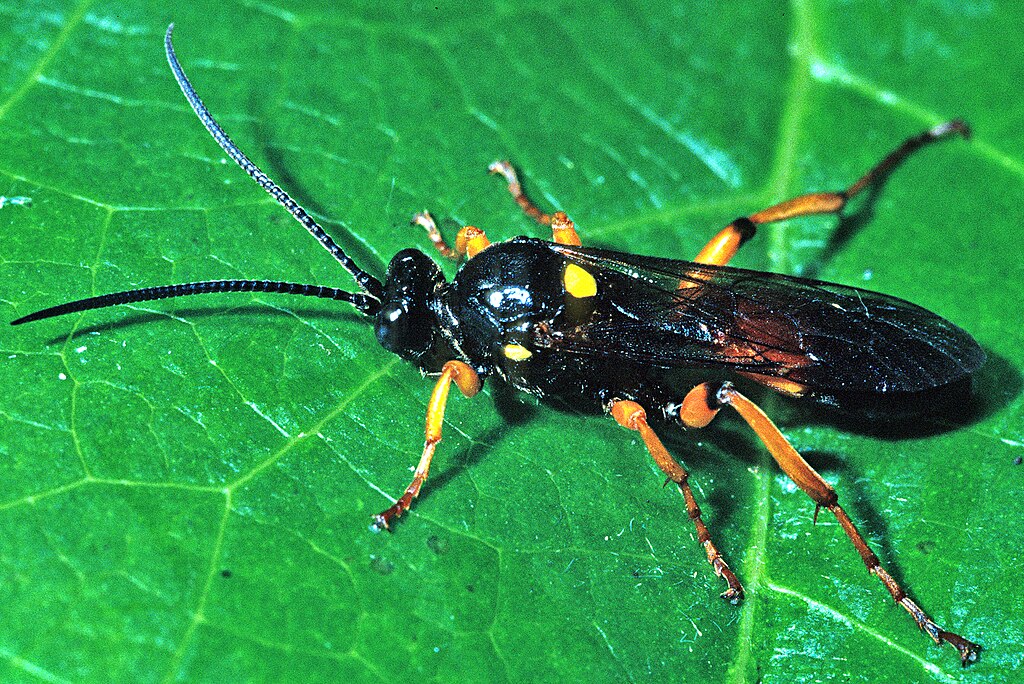

The late 1970s through the 1990s saw the emergence of insect-inspired aliens that combined our earthly bug fears with cosmic terror. Ridley Scott’s “Alien” (1979) featured a xenomorph with an exoskeleton, acid blood, and parasitic reproductive cycle that clearly drew inspiration from Earth’s insects, particularly parasitoid wasps. Paul Verhoeven’s “Starship Troopers” (1997) presented an entire civilization of “Bugs” as humanity’s existential enemy, using the insect-like Arachnids as vehicles for social satire and commentary on militarism. These films tapped into the notion that if alien life exists, it might resemble insects more than mammals, given the evolutionary success of arthropods on Earth. The merging of insect characteristics with alien beings created a new kind of monster that felt both familiar and utterly foreign. This synthesis of the terrestrial and extraterrestrial proved particularly effective at generating both visceral disgust and intellectual terror.

Digital Insects: CGI Revolutionizes Bug Horror

The advent of sophisticated computer-generated imagery in the 1990s transformed how bug monsters could be portrayed on screen. Films like “Mimic” (1997), directed by Guillermo del Toro, featured genetically engineered cockroaches that could mimic human form, rendered with unprecedented realism. “Starship Troopers” showcased swarms of alien insects that would have been impossible to create with practical effects alone. The digital revolution allowed filmmakers to depict insects at any scale and in any number, creating truly overwhelming scenarios of infestation. CGI enabled the creation of hybrid creatures with anatomically precise insect features combined with other animal or human characteristics. This technological advancement coincided with growing scientific understanding of insect biology, resulting in more plausible and therefore more disturbing monster designs that reflected actual insect anatomy and behaviors.

The Ecological Dimension: Environmental Themes in Bug Cinema

As environmental awareness grew from the 1990s onward, bug monster movies increasingly incorporated ecological themes and warnings. Films like “The Nest” (1988) and “Ticks” (1993) featured insects mutated by pollution or chemicals, while M. Night Shyamalan’s “The Happening” (2008) suggested that plants could trigger insect behavior changes as defense against human environmental destruction. These narratives reflected growing concerns about how human activities might disrupt natural systems in unpredictable ways. Bug monsters became perfect vehicles for exploring humanity’s fraught relationship with nature and the potential consequences of environmental tampering. The inherent “otherness” of insects made them ideal antagonists in stories about nature’s revenge against humanity. This ecological dimension added new layers of relevance to the bug monster subgenre, connecting ancient fears of insects to contemporary anxieties about climate change and biodiversity loss.

Psychological Infestation: Bugs and Mental Health

Some of the most disturbing bug monster films have explored the intersection of insect infestation and psychological breakdown. William Friedkin’s “Bug” (2006) brilliantly blurred the line between actual infestation and paranoid delusion, while “Slither” (2006) featured mind-controlling parasites that raised questions about identity and autonomy. These films tap into the particularly disturbing concept of insects invading not just our environments but our minds and bodies. The crawling sensation of insects on skin (formication) is a common symptom in certain psychological conditions and drug withdrawals, creating a potent connection between insect imagery and mental distress. Films exploring this territory often leave viewers questioning the reliability of what they’re seeing, mirroring the confusion of characters who cannot trust their own perceptions. This psychological dimension represents one of the most sophisticated evolutions of bug monster cinema, moving from external threats to internal horrors.

Insect Apocalypse: Swarms as Existential Threat

The concept of insect swarms overwhelming humanity has become increasingly prevalent in modern bug monster films. Movies like “The Mist” (2007) and “Black Swarm” (2007) depict scenarios where massive numbers of insects or insect-like creatures threaten human extinction. These narratives draw power from real-world concerns about potential ecological collapse and insect population dynamics. The visual impact of countless insects moving as a unified force creates a particularly effective cinematic horror, suggesting that individual human action becomes meaningless against such overwhelming numbers. These films often feature scenes of insects breaching supposedly secure human environments, undermining our sense of separation from the natural world. The swarm narrative reflects anxieties about overpopulation, resource competition, and humanity’s potentially precarious position in the global ecosystem despite our technological advantages.

Sympathetic Monsters: Humanizing the Insect

Not all insect-based cinema has focused on horror—some films have attempted to humanize or create sympathy for bug characters. “Joe’s Apartment” (1996) featured talking cockroaches as comedic sidekicks, while Pixar’s “A Bug’s Life” (1998) created an entire society of relatable insect characters. Even some horror-adjacent films like “District 9” (2009), with its insect-like aliens called “prawns,” generated sympathy for creatures that physically resembled arthropods. These humanizing approaches reflect growing scientific appreciation for the ecological importance and complex behaviors of insects. By giving insects voices, personalities, and emotional lives, these films challenge the reflexive disgust many humans feel toward arthropods. This trend represents an interesting counterpoint to the horror tradition, suggesting that our relationship with insects might be more complex than simple fear and revulsion.

Hybrid Horrors: Combining Human and Insect

Some of the most disturbing modern bug monsters are hybrids that combine human and insect characteristics in unsettling ways. Films like “The Human Centipede” series (2009-2015) take inspiration from insect body plans to create human monstrosities, while “Splice” (2009) features a genetically engineered creature with both mammalian and insect traits. The Japanese film “Tetsuo: The Iron Man” (1989) presented a man transforming into a mechanical being with distinctly insect-like qualities. These hybrid creations speak to anxieties about biotechnology, genetic engineering, and the blurring boundaries between species. By merging human and insect characteristics, these films create particularly uncanny monsters that violate our sense of natural categories. The psychological impact of these hybrids stems from their location in an uncomfortable middle ground—neither fully human nor fully insect, they exist in a disturbing liminal space that challenges our understanding of what constitutes humanity.

The Future of Bug Cinema: New Technologies and Persistent Fears

As we look to the future of bug monster movies, several trends are emerging that suggest the continued evolution of this resilient subgenre. Virtual reality and immersive technologies promise to create even more visceral experiences of insect invasion, potentially allowing viewers to feel surrounded by virtual bugs. Scientific advances in entomology continue to reveal strange and wonderful insect behaviors that could inspire new cinematic monsters based on real biological principles rather than mere speculation. Climate change and habitat destruction are already altering insect populations worldwide, creating real-world scenarios that could inspire new ecological horror narratives. Meanwhile, developments in robotics and drone technology draw inspiration from insect morphology and swarm behavior, creating new anxieties about technology that could manifest in future bug-inspired sci-fi horror. Whatever form they take, bug monsters seem certain to maintain their hold on our collective imagination, continuing to evolve alongside our technologies and anxieties.

Conclusion

From the rubber-suited giants of the atomic age to the photorealistic horrors of today, bug monsters have undergone a remarkable cinematic evolution. This transformation reflects not just advances in special effects technology but deeper shifts in our cultural relationship with insects and the natural world. As we’ve seen, these chitinous creatures have served as vehicles for exploring everything from nuclear anxiety to environmental collapse, from body horror to psychological disintegration. Their enduring presence on our screens speaks to something fundamental in human psychology—perhaps an evolutionary memory of our ancient competition with insects, or a recognition of their alien yet successful design. Whatever the source of their power to disturb us, bug monsters have proven themselves to be among cinema’s most adaptable and persistent creatures, continuing to evolve new forms to frighten new generations of moviegoers. As long as insects continue to crawl, slither, and fly through our world, they will undoubtedly continue to inspire some of our most memorable cinematic nightmares.