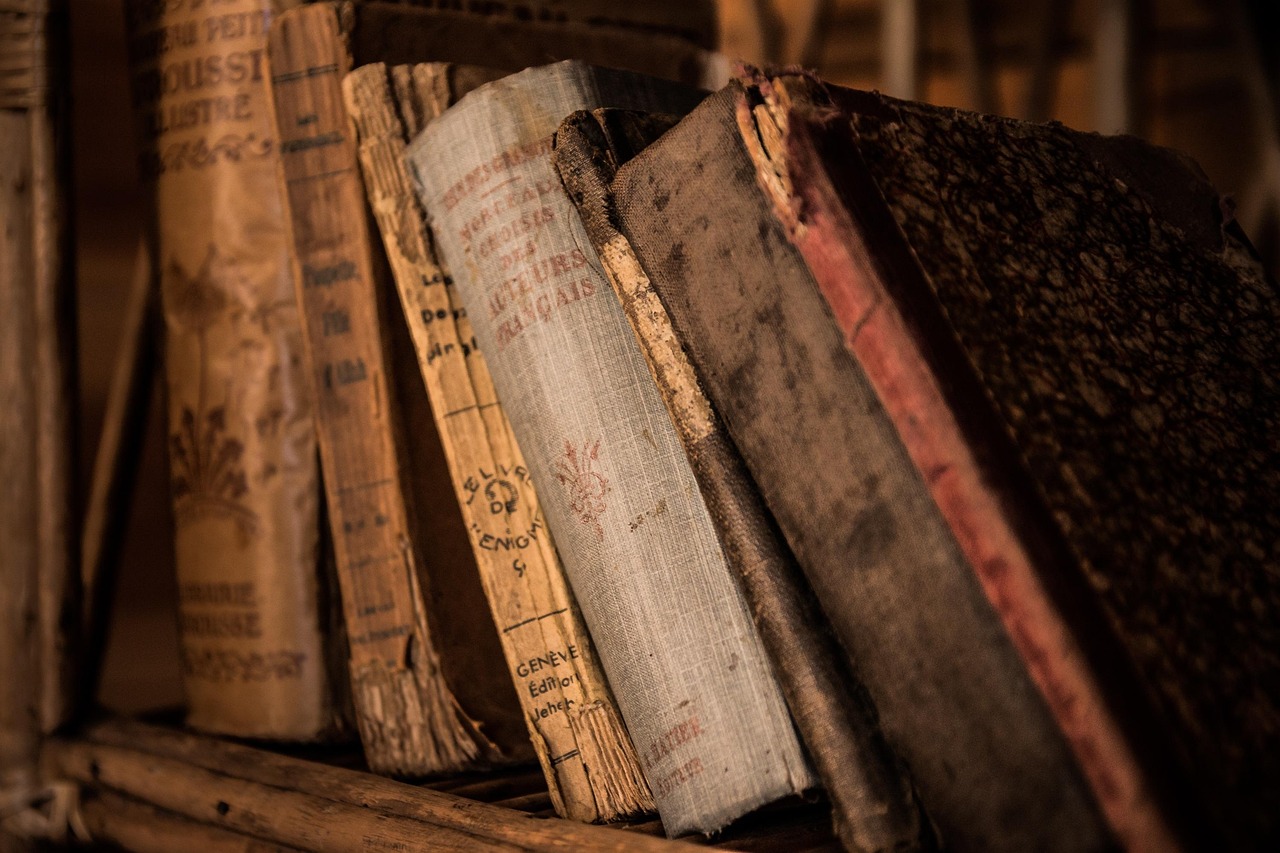

Picture this: you’re browsing through your grandmother’s dusty library, pulling out a beloved childhood book, only to find tiny holes scattered across the pages like confetti. What you’re witnessing isn’t just age-related decay—it’s the handiwork of one of nature’s most persistent literary critics. These microscopic vandals have been quietly devouring human knowledge for centuries, turning precious manuscripts into Swiss cheese and leaving librarians worldwide in a state of perpetual panic.

The culprits behind this bibliographic destruction are far more fascinating than you might imagine. These aren’t your typical garden-variety insects; they’re specialized creatures that have evolved to feast on the very foundation of human civilization. From ancient scrolls in Egyptian tombs to modern paperbacks in your local bookstore, these tiny terrors have been dining on literature longer than most species have existed.

Meet the Silverfish: The Original Book Destroyer

Silverfish are the undisputed champions of literary destruction, earning their fearsome reputation through millennia of page-munching prowess. These primitive insects, scientifically known as Lepisma saccharina, have remained virtually unchanged for over 400 million years, making them living fossils with an insatiable appetite for cellulose. Their sleek, metallic appearance and fish-like movements give them an almost otherworldly quality as they dart across book spines in the dead of night.

What makes silverfish particularly notorious is their ability to digest cellulose, the primary component of paper, thanks to special enzymes in their gut. They don’t just nibble randomly—they’re strategic feeders who target the protein-rich glues and starches used in book binding. This calculated approach means they can systematically dismantle entire volumes, starting from the binding and working their way through the pages with surgical precision.

The Booklouse: Small but Mighty Paper Predator

Don’t let their diminutive size fool you—booklice pack a devastating punch when it comes to manuscript mayhem. These tiny insects, measuring less than 2 millimeters in length, belong to the order Psocoptera and are often mistaken for dust particles until they start moving. Their preference for humid environments makes them particularly troublesome in libraries, archives, and poorly ventilated storage areas where books are kept.

Booklice feed on the mold and fungus that grows on paper in damp conditions, but they’re not above chomping directly on the paper itself when other food sources are scarce. Their feeding habits create a domino effect—as they consume the surface materials, they weaken the paper’s structural integrity, making it more susceptible to further damage. What’s particularly insidious is their ability to reproduce rapidly in optimal conditions, with a single female capable of laying up to 200 eggs in her lifetime.

Termites: The Underground Library Raiders

While most people associate termites with wooden structures, these relentless insects have a lesser-known passion for paper products that rivals their appetite for timber. Subterranean termites, in particular, view books as an all-you-can-eat buffet, especially when libraries are built with wooden foundations or shelving systems that provide easy access routes. Their highly organized social structure means that once they discover a book collection, they can mobilize entire colonies to systematically harvest the cellulose-rich pages.

The damage termites inflict on books is often more severe than other paper-eating insects because they work in coordinated groups. Unlike the solitary silverfish, termites operate like a well-oiled machine, with worker termites carving intricate tunnels through book spines while others transport the digested material back to the colony. This collaborative approach can reduce centuries-old manuscripts to hollow shells in a matter of weeks, making termites perhaps the most feared enemy of archivists and librarians worldwide.

The Science Behind Paper Consumption

Understanding how insects can actually digest paper requires diving into the fascinating world of enzymatic breakdown and microbial partnerships. Most paper-eating insects possess specialized gut bacteria that produce cellulase enzymes, which break down the complex cellulose molecules into simple sugars that can be absorbed and metabolized. This symbiotic relationship between insects and bacteria is so effective that it rivals the digestive capabilities of large herbivorous mammals.

The process begins when insects physically break down paper fibers through chewing, creating smaller particles that can be more easily processed by their digestive systems. The cellulose then encounters the bacterial enzymes in the insect’s gut, where it undergoes hydrolysis—a chemical reaction that splits the molecular bonds holding the cellulose together. This remarkable biological process allows creatures weighing mere grams to consume materials that would be completely indigestible to humans and most other animals.

Historical Devastation: Famous Cases of Book-Eating Disasters

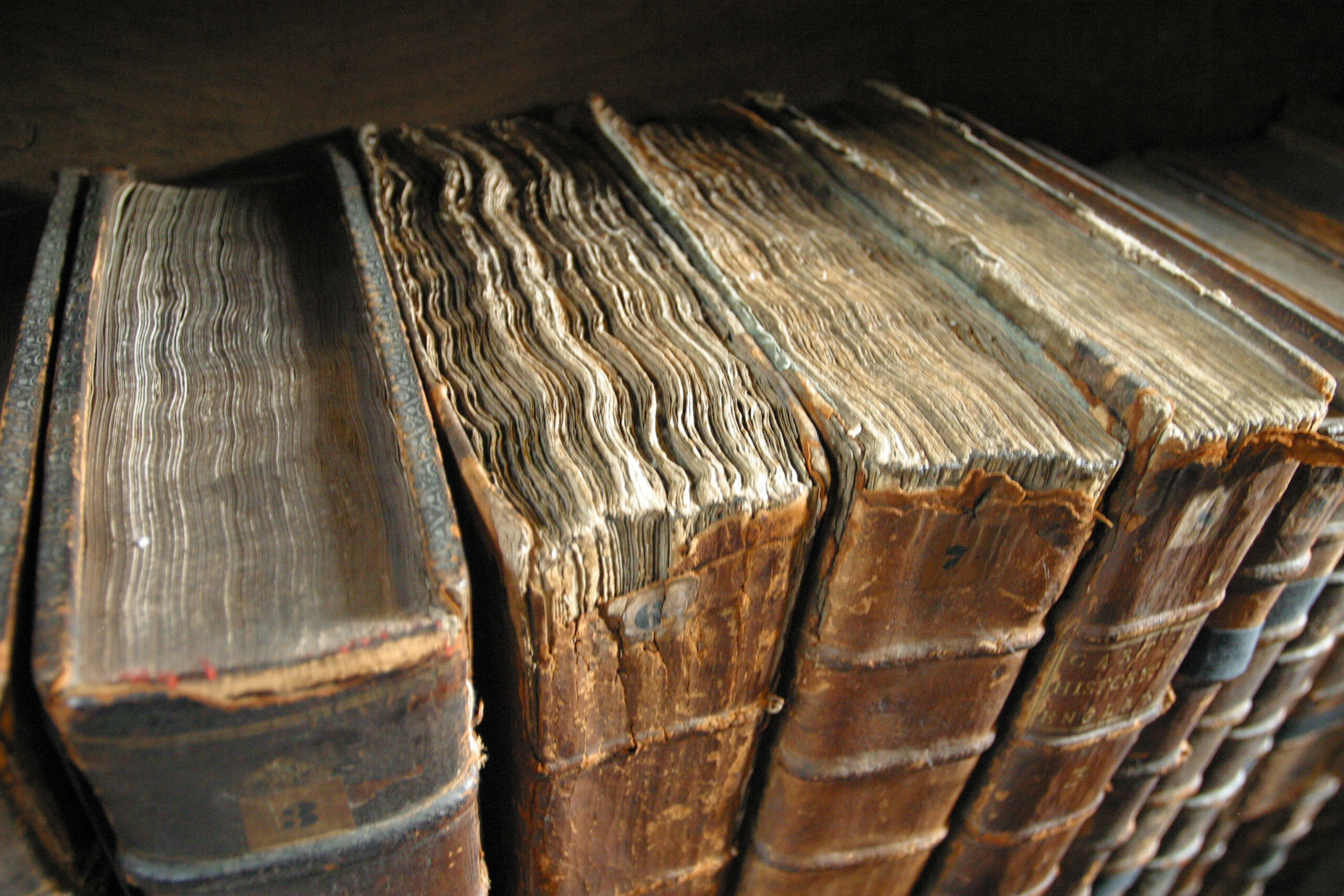

Throughout history, book-eating insects have left their mark on some of humanity’s most precious literary treasures, creating losses that can never be fully recovered. The Library of Alexandria, while primarily destroyed by fire and human conflict, also suffered ongoing damage from various paper-eating insects that thrived in the Mediterranean climate. Medieval monasteries reported constant battles with “book worms,” a catch-all term for various larvae and insects that would tunnel through parchment manuscripts, sometimes destroying years of painstaking work overnight.

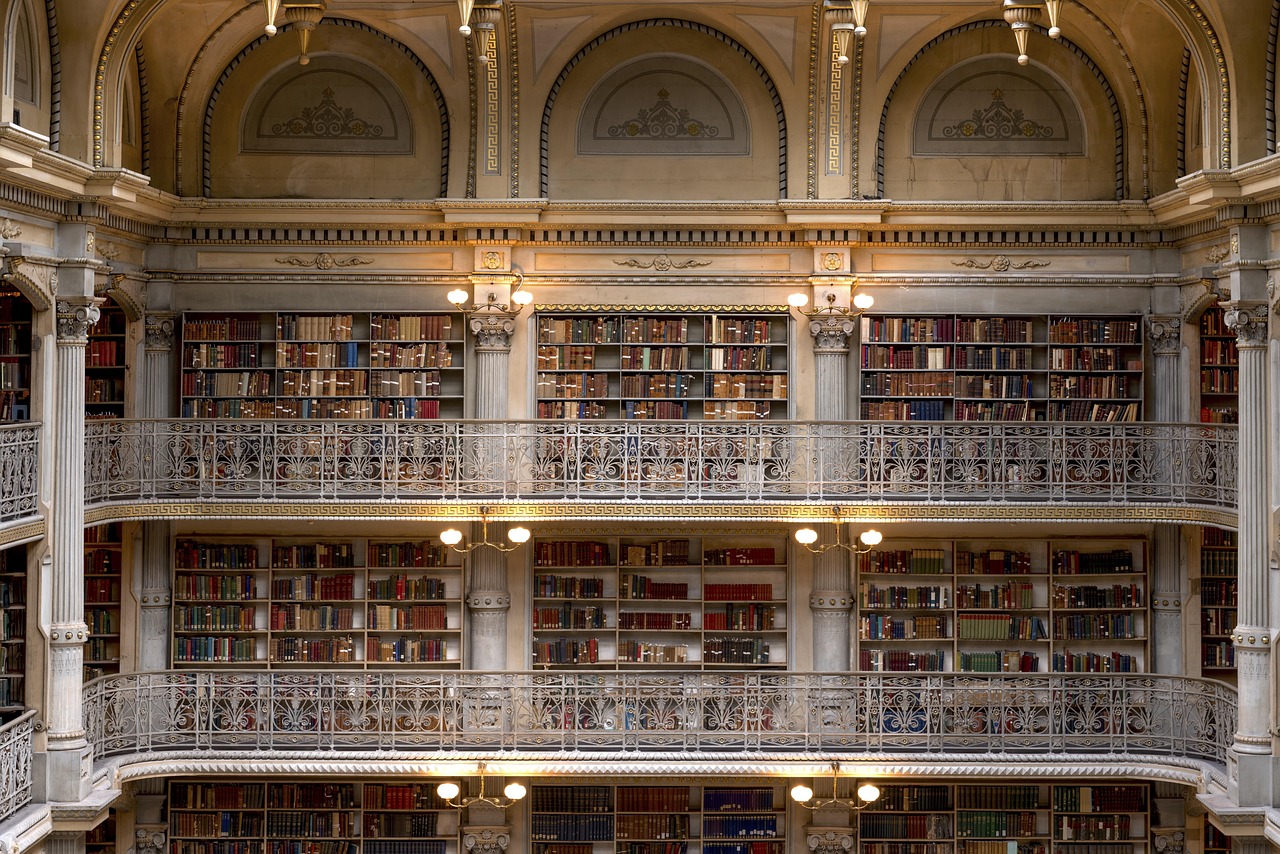

One of the most documented cases occurred in the 19th century at the British Museum, where a severe infestation of booklice and silverfish caused irreparable damage to thousands of rare manuscripts and books. The incident led to the development of some of the first systematic pest control methods specifically designed for libraries and archives. Even today, major institutions like the Vatican Library and the Smithsonian continue to wage ongoing wars against these microscopic marauders, employing everything from climate control to specialized fumigation techniques.

Modern Library Defense Systems

Today’s libraries and archives have transformed into high-tech fortresses designed to keep book-eating insects at bay through sophisticated environmental controls and monitoring systems. Climate control has become the first line of defense, with humidity levels maintained between 45-55% to prevent the damp conditions that attract booklice and encourage mold growth. Temperature regulation keeps storage areas cool enough to slow insect reproduction cycles while remaining warm enough to prevent condensation that could damage books.

Integrated pest management systems now employ everything from pheromone traps to detect early infestations to specialized air filtration systems that remove insect eggs and larvae from the environment. Many institutions use frozen quarantine protocols for new acquisitions, exposing potentially infested materials to sub-zero temperatures that kill insects in all life stages. Some cutting-edge facilities even employ beneficial insects like predatory mites that hunt down and eliminate book-eating pests without causing damage to the collections themselves.

The Economics of Book Bug Damage

The financial impact of book-eating insects extends far beyond simple replacement costs, creating ripple effects throughout the cultural and academic sectors that are difficult to quantify. Insurance companies estimate that insect damage to books, documents, and archives costs institutions worldwide hundreds of millions of dollars annually in direct losses, not including the incalculable value of irreplaceable historical materials. University libraries alone spend millions each year on preventive pest control measures and climate control systems designed to protect their collections.

The hidden costs include staff time spent on monitoring and treatment, specialized storage equipment, and the ongoing expenses of maintaining optimal environmental conditions. When rare books or manuscripts are damaged, the loss often extends beyond monetary value to include cultural heritage that simply cannot be replaced. Some institutions have found that the cost of prevention is actually lower than the potential losses from a single major infestation, making investment in bug-proofing measures a sound financial decision.

Home Library Protection: Keeping Your Books Safe

Protecting your personal book collection from these literary predators doesn’t require a museum-level budget, but it does demand attention to detail and consistent maintenance practices. The most effective home defense strategy starts with controlling humidity levels using dehumidifiers or air conditioning, especially in basements, attics, and other areas where moisture tends to accumulate. Regular vacuuming around bookshelves removes insect eggs and larvae before they can establish themselves, while proper ventilation prevents the stagnant air conditions that many book-eating insects prefer.

Storage techniques play a crucial role in home library protection, with books ideally kept at least six inches away from walls and floors where insects commonly travel. Cedar blocks or lavender sachets placed strategically around bookshelves can act as natural deterrents, though their effectiveness varies depending on the specific insect species involved. Regular inspection of books, particularly older volumes with organic bindings, allows for early detection of infestations before they can spread throughout an entire collection.

The Digital Age: Are E-Books Really Bug-Proof?

While electronic books might seem like the perfect solution to insect-related literary destruction, the reality is more complex than simply switching from paper to pixels. E-readers and tablets themselves are immune to book-eating insects, but the infrastructure supporting digital libraries faces its own unique vulnerabilities. Server farms and data centers, which house millions of digital books, require constant climate control and pest management to protect the hardware from insects that can cause electrical shorts and equipment failures.

The transition to digital formats has certainly reduced the overall vulnerability of human knowledge to insect damage, but it hasn’t eliminated the threat entirely. Physical books continue to hold cultural and practical value that digital versions can’t fully replace, meaning that protecting traditional libraries and archives remains as important as ever. Additionally, the environmental footprint of maintaining digital collections through energy-intensive data centers raises questions about whether the cure might be worse than the disease in some cases.

Beneficial Aspects: When Book Bugs Actually Help

Surprisingly, not all interactions between insects and books are destructive—some actually contribute to the preservation and understanding of literary works in unexpected ways. Forensic entomologists have used insect damage patterns to date manuscripts and determine their geographic origins, with different species leaving characteristic signatures that can provide valuable historical information. The presence of certain insects in old books can even indicate the authenticity of a work, as forgers rarely go to the trouble of introducing period-appropriate insect damage.

In ecological terms, book-eating insects play important roles in breaking down organic matter and recycling nutrients back into natural systems. Their ability to digest cellulose makes them valuable decomposers in forest ecosystems, where they help process fallen leaves and dead plant material. Some researchers have even explored using the cellulase enzymes produced by these insects for industrial applications, including biofuel production and sustainable paper manufacturing processes.

Future Innovations in Book Protection

The battle against book-eating insects continues to evolve with advances in technology and our understanding of insect behavior, leading to innovative solutions that would have seemed like science fiction just decades ago. Researchers are developing smart materials that can detect insect presence through chemical sensors embedded in book bindings, providing early warning systems that alert librarians to potential infestations before visible damage occurs. Nanotechnology applications include microscopic coatings that make paper surfaces hostile to insects while remaining invisible and harmless to human readers.

Genetic research into insect pheromones has led to highly targeted lure systems that can eliminate specific species without affecting beneficial insects or the broader ecosystem. Some institutions are experimenting with controlled atmosphere storage, using modified air compositions that are lethal to insects but safe for books and humans. The future may even see the development of genetically modified beneficial insects specifically designed to hunt down and eliminate paper-eating pests in library environments.

Global Perspectives: Different Bugs, Different Continents

The specific insects that threaten books vary dramatically across different geographic regions, creating unique challenges for libraries and archives around the world. Tropical climates foster different species than temperate zones, with some insects like the varied carpet beetle being particularly problematic in North American libraries, while Mediterranean regions deal more frequently with specific types of booklice and silverfish. Asian libraries often contend with rice weevils and other grain-eating insects that have adapted to paper consumption, while Australian institutions face unique challenges from native insect species that don’t exist elsewhere.

These regional differences have led to the development of specialized pest management strategies tailored to local conditions and indigenous insect populations. International cooperation between libraries and archives has become increasingly important, with institutions sharing information about effective treatments and prevention methods. Climate change is also altering traditional insect distribution patterns, forcing libraries to adapt their protection strategies as new species expand their ranges into previously safe territories.

The Psychology of Book Destruction

For many people, the idea of insects eating books triggers a visceral emotional response that goes beyond simple concern for property damage. Books represent knowledge, culture, and personal memories, making their destruction feel like an attack on human civilization itself. This psychological dimension helps explain why librarians and book lovers often describe insect infestations in almost military terms, using language typically reserved for discussing invasions or battles.

The fear of book-eating insects taps into deeper anxieties about the fragility of human knowledge and the constant threat of losing our cultural heritage to forces beyond our control. Many collectors report feeling genuinely distressed when they discover insect damage in their personal libraries, describing it as a violation of sacred space. This emotional component drives much of the innovation in book protection, as people are willing to invest significant resources in protecting what they perceive as irreplaceable treasures.

These tiny creatures have been reshaping human knowledge for millennia, forcing us to constantly adapt our methods of preserving and protecting the written word. While modern technology has given us powerful tools to combat these literary predators, the battle is far from over. The next time you notice a small hole in an old book, remember that you’re witnessing the aftermath of an ancient war between humans and insects—a conflict that has shaped the very survival of human knowledge. What will you do to protect your own piece of literary history?