Exploring the world of spiders can be a fascinating journey into one of nature’s most successful evolutionary stories. While many people harbor fears of these eight-legged creatures, the truth is that most spiders pose no threat to humans and are actually beneficial for our ecosystems. Non-venomous spiders, or those with venom too weak to affect humans, offer incredible opportunities for safe wildlife observation. Their diverse hunting strategies, intricate web designs, and fascinating behaviors make them perfect subjects for nature enthusiasts, photographers, and curious minds alike. This article explores some of the most interesting non-venomous spider species you can safely observe in their natural habitats, highlighting their unique characteristics and where you might find them.

Understanding Spider Safety

Before venturing out to observe spiders in the wild, it’s important to understand a few key facts about spider venom and safety. Technically speaking, almost all spiders possess venom, which they use to subdue their prey. However, the vast majority of spiders have venom that is either too weak to affect humans or fangs that are unable to penetrate human skin. The spiders featured in this article are considered “non-venomous” in the practical sense that they pose no significant risk to human observers. When observing any wildlife, including spiders, it’s best to maintain a respectful distance and avoid handling them, both for your safety and the spider’s wellbeing. Remember that these creatures play vital roles in their ecosystems, controlling insect populations and serving as food for other animals.

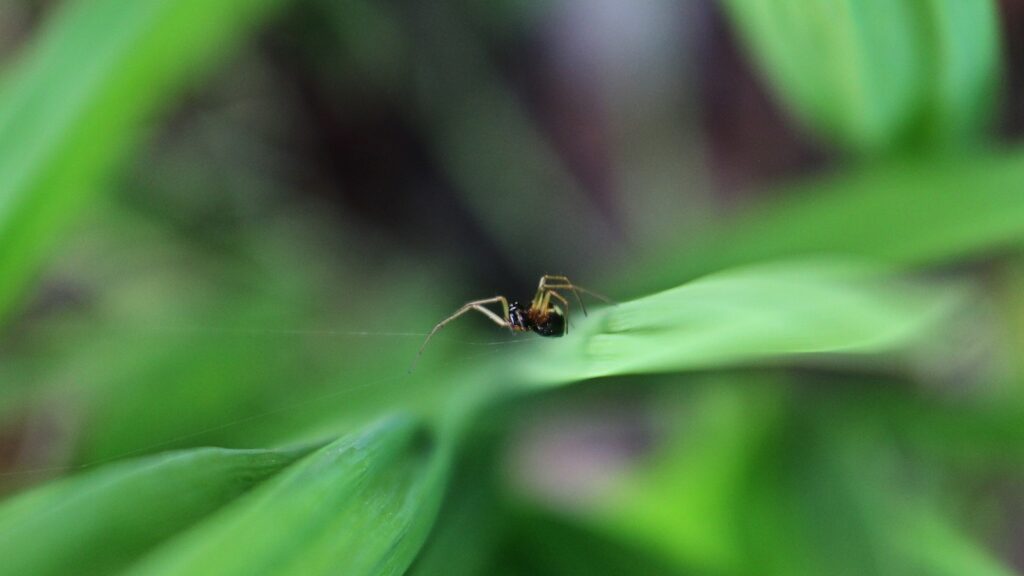

Jumping Spiders: Nature’s Curious Acrobats

Jumping spiders (family Salticidae) represent some of the most charismatic arachnids you can encounter in the wild. With their large forward-facing eyes, these small spiders possess remarkable vision that allows them to stalk and pounce on prey with incredible precision. Unlike many other spiders, jumpers don’t rely on webs for hunting; instead, they use silk safety lines as they leap distances up to 50 times their body length. Their inquisitive nature makes them particularly enjoyable to observe, as they often turn to look directly at human observers, tilting their heads and seeming to study you as much as you’re studying them. Found on every continent except Antarctica, jumping spiders display a diversity of colorations, from the metallic greens and blues of the peacock jumping spider to the fuzzy “panda face” patterns of the Phidippus species common in North America.

Orb Weavers: Masters of Geometric Architecture

Orb weavers (family Araneidae) create some of the most visually striking and recognizable spider webs in the world. Their classic wheel-shaped webs are engineering marvels, with precise spacing and structural integrity that humans have studied for biomimetic applications. Species like the golden silk orb-weaver (Nephila clavipes) and the black and yellow garden spider (Argiope aurantia) construct large webs that can span several feet across, making them easy to spot and observe in gardens, meadows, and forest edges. These spiders are typically colorful and relatively large, with distinctive markings that make identification accessible even to novice naturalists. Dawn and dusk are particularly good times to observe orb weavers, as they’re often busy repairing their webs or catching prey during these hours, though many species can be seen centered in their webs throughout the day.

Wolf Spiders: Ground-Dwelling Hunters

Wolf spiders (family Lycosidae) offer a completely different observation experience compared to web-building species. These robust hunters actively pursue their prey rather than waiting in webs, using speed and strength to capture insects and other small invertebrates. A nighttime observation with a flashlight reveals one of their most distinctive features—their eyes reflect light like tiny diamonds in the darkness, making them easy to spot. Female wolf spiders demonstrate remarkable maternal care, carrying their egg sacs attached to their spinnerets and, after hatching, carrying dozens of spiderlings on their backs for several days. Found in diverse habitats from deserts to woodlands, these spiders can often be observed in leaf litter, under logs, or simply running across open ground during warmer months. The larger species, like the Carolina wolf spider (Hogna carolinensis), can grow over an inch in body length, making them particularly impressive to observe in action.

Crab Spiders: Masters of Camouflage

Crab spiders (family Thomisidae) earn their name from their distinctive crab-like appearance and sideways walking style. These ambush predators demonstrate some of the most impressive camouflage abilities in the spider world, with many flower-dwelling species able to change color to match their surroundings over several days. The goldenrod crab spider (Misumena vatia), for example, can shift between white and yellow depending on the flower it inhabits. Unlike active hunters or web builders, crab spiders are “sit-and-wait” predators that remain motionless on flowers, often perfectly camouflaged, waiting for pollinators like bees and butterflies to come within striking distance. Their front two pairs of legs are noticeably longer and stronger than their back legs, allowing them to quickly grasp prey many times their size. Finding these spiders can be challenging due to their excellent camouflage, making the discovery all the more rewarding for patient observers.

Fishing Spiders: Aquatic Arachnid Specialists

Fishing spiders (genus Dolomedes) offer a fascinating glimpse into how spiders have adapted to exploit aquatic environments. These large spiders can walk on water using surface tension and specialized hairs on their legs that repel water. They hunt by detecting vibrations on the water’s surface from struggling insects or even small fish and tadpoles. When hunting, fishing spiders extend their front legs onto the water surface, essentially using it as an extended sensory organ to detect prey movements. Some species can even dive underwater for short periods to escape predators or capture prey, surrounding themselves with a thin layer of air trapped by their body hairs. Look for these impressive arachnids around the edges of ponds, streams, and lakes, particularly in the evening hours when they’re most active. The dark fishing spider (Dolomedes tenebrosus), one of North America’s largest spider species, can have a leg span of over three inches, making it an impressive sight.

Huntsman Spiders: Fast-Moving Forest Giants

Huntsman spiders (family Sparassidae) represent some of the most impressive non-web-building spiders in terms of sheer size. With leg spans that can exceed 12 inches in some species, these fast-moving hunters are often mistakenly feared due to their imposing appearance. Despite their intimidating size, huntsman spiders are shy, non-aggressive, and possess venom that isn’t dangerous to humans. Their flattened bodies allow them to squeeze into remarkably narrow crevices, which is why they’re sometimes called “wood spiders” or “flat spiders” in different regions. In warmer climates worldwide, huntsman spiders can be observed on tree trunks, under bark, or on rocky outcroppings where they hunt at night. The Heteropoda species found in Asia and Australia are particularly impressive specimens for wildlife observation, though in the United States, the pantropical huntsman (Heteropoda venatoria) can be found in Florida and Gulf Coast states.

Harvestmen: The Spider-Like Non-Spiders

While not true spiders, harvestmen (order Opiliones) – commonly called “daddy longlegs” – are arachnids often confused with spiders and make excellent subjects for wildlife observation. Unlike spiders, harvestmen have a single-segmented body, no silk glands, no venom, and typically eight extremely long legs. These gentle creatures are completely harmless to humans and feed primarily on decomposing plant and animal matter, though some species are predatory on small insects. Harvestmen can be found in moist environments like forests, where they hide under logs and rocks during the day and emerge at night to forage. Some species demonstrate fascinating defensive behaviors, including releasing repellent chemicals, playing dead, or even detaching a leg if grabbed by a predator – the detached leg continues to twitch, distracting the predator while the harvestman escapes. In some parts of the world, harvestmen gather in massive aggregations of hundreds or thousands of individuals, creating a spectacular natural display.

Tarantulas: Gentle Giants of the Spider World

Despite their fearsome reputation, most tarantulas (family Theraphosidae) are docile creatures that pose little threat to humans. While they do possess venom, their bites typically cause only mild discomfort similar to a bee sting, and many species are reluctant to bite, preferring to retreat or use defensive hair-flicking behavior when threatened. North American species like the desert blond tarantula (Aphonopelma chalcodes) can often be observed during their breeding seasons when males wander in search of females. These long-lived arachnids (females can live 20-30 years in the wild) move deliberately and are relatively easy to observe with patience. The best time to spot tarantulas in the wild is during warm evenings, particularly after rain, when they may emerge from their burrows to hunt. In the southwestern United States, dedicated “tarantula festivals” are even held during migration seasons when males are most visible, allowing nature enthusiasts to safely observe these impressive arachnids.

Funnel Weavers: Masters of the Silk Tunnel

Funnel weavers (family Agelenidae) construct distinctive sheet webs with a funnel-shaped retreat where the spider hides, waiting for prey to stumble onto its web. These spiders are often confused with the medically significant Sydney funnel-web spider, but the common grass spider (Agelenopsis species) and other true funnel weavers in North America and Europe are harmless to humans. Their webs are most visible in the early morning when covered with dew, stretching across lawns, fields, and woodland floors. Funnel weavers are incredibly fast, rushing out from their silken tunnels when they detect prey vibrations, then quickly retreating with their captured meal. These spiders can be safely observed throughout the warmer months in most temperate regions, with their numbers becoming particularly noticeable in late summer and fall. When observing funnel weaver webs, patient watchers may be rewarded with seeing the impressive speed of these spiders as they dart out to capture prey—they’re among the fastest spiders in North America.

Cellar Spiders: Delicate Web Architects

Cellar spiders (family Pholcidae), often called “daddy longlegs spiders” (not to be confused with harvestmen), are characterized by their extremely long, delicate legs and small bodies. These spiders construct loose, irregular webs in corners of caves, rock outcroppings, and human structures, where they hang upside down waiting for prey. One of their most fascinating defensive behaviors is their rapid vibration when disturbed—they can shake their web so vigorously that they become a blur, making it difficult for predators to target them. Despite urban myths, cellar spiders are completely harmless to humans, with venom designed to subdue small insects. They’re interesting to observe because of their unique hunting technique; when prey becomes entangled in their web, cellar spiders throw additional silk strands to further immobilize it before approaching. In natural settings, these spiders can be found in cave entrances, under rock ledges, and in other protected areas where their webs can be built undisturbed.

Garden Spiders: Backyard Wildlife Ambassadors

Garden spiders, particularly the striking black and yellow argiope (Argiope aurantia), serve as perfect “gateway” species for people beginning to appreciate arachnids. Their large size (females can reach over an inch in body length), distinctive yellow and black markings, and habit of building webs at eye level make them impossible to miss in gardens and meadows throughout North America. The distinctive zigzag pattern of silk (called a “stabilimentum”) that runs through the center of their webs is thought to either attract insects, prevent birds from flying through the web, or advertise the spider’s presence to larger animals. These beneficial predators consume large numbers of garden pests and are completely harmless to humans, making them valuable allies in natural pest control. Garden spiders tend to remain in one location if undisturbed, allowing for repeated observations of the same individual as it repairs its web, captures prey, and eventually produces its distinctive egg sac in late summer or fall.

Tips for Successful Spider Observation

Successful spider observation begins with knowing when and where to look. Many species are most active during dawn, dusk, or nighttime hours, though web-dwelling species can often be observed throughout the day. A good-quality flashlight is essential for nighttime observation, as the reflection from spiders’ eyes makes them much easier to spot. Moving slowly and deliberately prevents you from disturbing spiders or damaging their webs, while a magnifying glass can reveal incredible details that aren’t visible to the naked eye. Photography enthusiasts should consider a macro lens and perhaps a small, diffused flash to capture details without harsh shadows. Keeping a field journal of your observations adds another dimension to the experience, allowing you to track behaviors, locations, and seasonal patterns over time. Remember to respect these animals’ habitats; observe without disturbing, and never collect spiders from protected areas or introduce non-native species into new environments.

Educational Benefits of Spider Observation

Observing spiders in their natural environments provides remarkable educational opportunities for people of all ages. For children, spider watching can spark early interest in natural sciences, teaching patience, observation skills, and respect for even the smallest creatures. Students can practice scientific methods through observation, hypothesis formation, and data collection about spider behaviors or habitat preferences. For adult naturalists, spiders offer accessible subjects for nature photography, sketching, or simply mindful observation that can be done in virtually any habitat, from urban parks to remote wilderness. Perhaps most importantly, direct observation of these often-misunderstood creatures helps dispel fears and myths, replacing arachnophobia with appreciation for these ecological important predators. Organizations like local nature centers, universities, and naturalist groups often offer guided spider walks that can provide expert context and identification tips for beginning observers.

Spider observation represents one of the most accessible forms of wildlife watching, requiring minimal equipment and available virtually everywhere humans live. From the architect-like precision of orb weavers to the curious, almost mammal-like awareness of jumping spiders, these eight-legged marvels offer windows into evolutionary adaptations that have allowed them to thrive for hundreds of millions of years. By focusing on non-venomous species, observers can safely enjoy these fascinating creatures without concern, potentially transforming fear into fascination. As more people learn to appreciate rather than fear spiders, conservation efforts for these vital predators and their habitats may also benefit. Whether you’re an experienced naturalist or simply curious about the natural world, the spiders in this article provide perfect starting points for an enriching wildlife observation experience.