When we think about our bodies, we often picture ourselves as singular entities. But the truth is far more complex and fascinating: the human body is actually a thriving ecosystem hosting trillions of microorganisms. Among these tiny inhabitants are specialized creatures that consume what we might consider waste products—dead skin cells, excess oils, sweat, and even hair. While the idea of bugs feeding on our bodies might initially sound repulsive, these microscopic companions play crucial roles in maintaining our health. They form an intricate part of our microbiome, the collection of bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms that live on and within us. This hidden world of beneficial bugs deserves our attention and appreciation, as they work tirelessly to keep our bodies in balance while consuming what we naturally shed.

The Human Microbiome: Your Personal Ecosystem

The human body hosts approximately 100 trillion microorganisms, collectively weighing about 2-5 pounds—roughly the same weight as your brain. This vast community of microbes, known as the microbiome, includes bacteria, fungi, viruses, and microscopic arthropods that have evolved alongside humans for millennia. Far from being passive hitchhikers, these organisms actively participate in maintaining our health through complex biochemical interactions. They help digest our food, produce essential vitamins, train our immune systems, and protect us from harmful pathogens by occupying ecological niches that might otherwise be filled by disease-causing organisms. Each person’s microbiome is unique, influenced by factors including genetics, diet, environment, and lifestyle, making it as individual as a fingerprint.

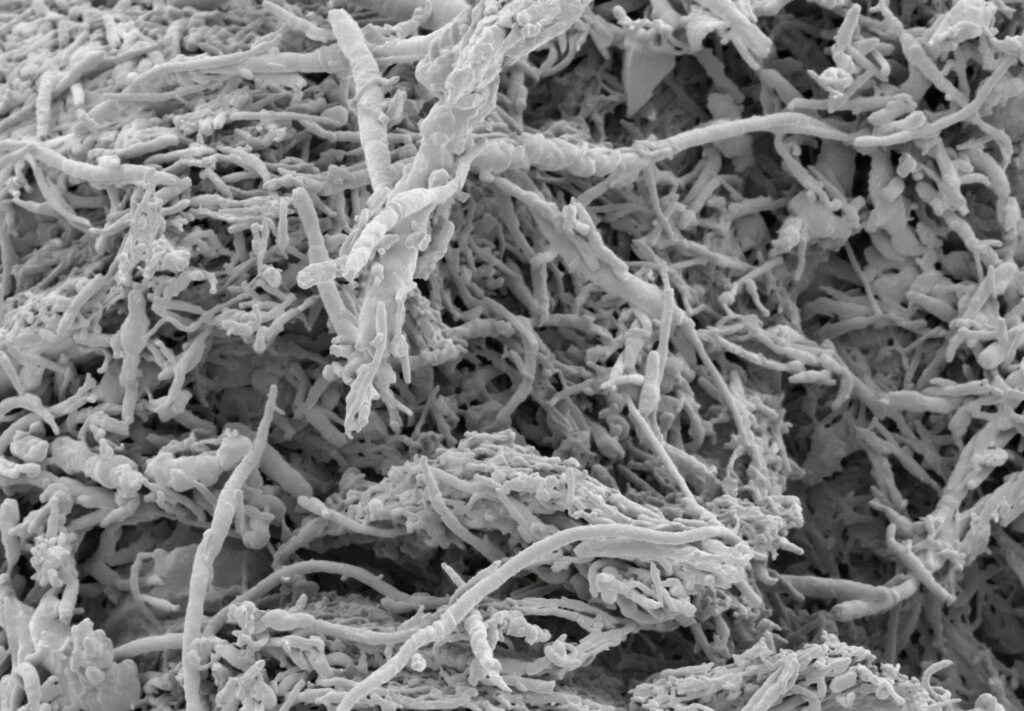

Demodex Mites: The Facial Dwellers

Among the most fascinating inhabitants of our skin are Demodex mites—microscopic eight-legged arthropods that primarily live in hair follicles and sebaceous glands on our faces. These tiny creatures, measuring less than half a millimeter in length, are particularly fond of our eyelashes, eyebrows, and the oily areas around our nose and cheeks. An estimated 90% of humans host these mites, with populations increasing as we age, yet most people remain completely unaware of their presence. Demodex mites feed primarily on sebum, the oily substance produced by our skin glands, and dead skin cells, essentially providing a cleaning service by consuming excess oils that might otherwise lead to clogged pores. They typically emerge at night to mate and move between follicles, returning to their protective hideaways before dawn.

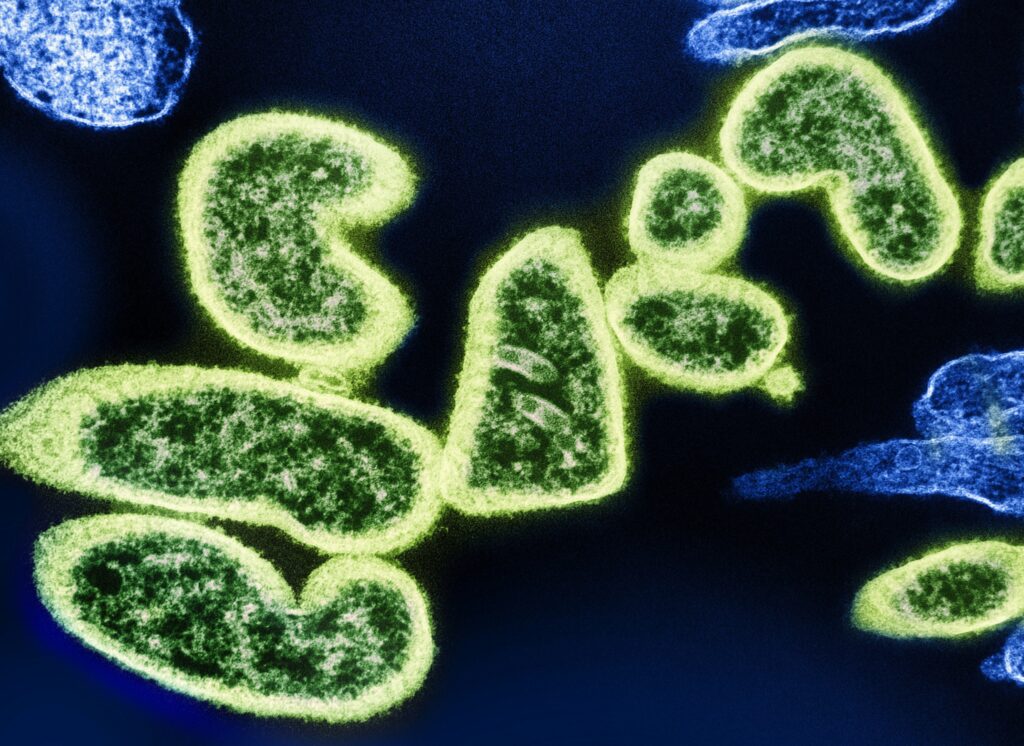

Malassezia: The Fungi That Manage Your Scalp

Malassezia is a genus of fungi that naturally inhabits the skin of many mammals, including humans, with particular concentration on oil-rich areas like the scalp, face, and upper torso. These lipophilic (oil-loving) yeasts feed on the lipids in sebum, breaking down oils that would otherwise accumulate excessively on our skin and scalp. In balanced quantities, Malassezia plays an important role in maintaining scalp health by regulating oil production and protecting against pathogenic microorganisms. However, an overgrowth of these fungi can contribute to conditions like dandruff, seborrheic dermatitis, and folliculitis, highlighting the delicate balance that must be maintained within our microbiome. Interestingly, the relationship between humans and Malassezia is so ancient that our immune systems have evolved to tolerate their presence, typically mounting minimal defensive responses against these fungi.

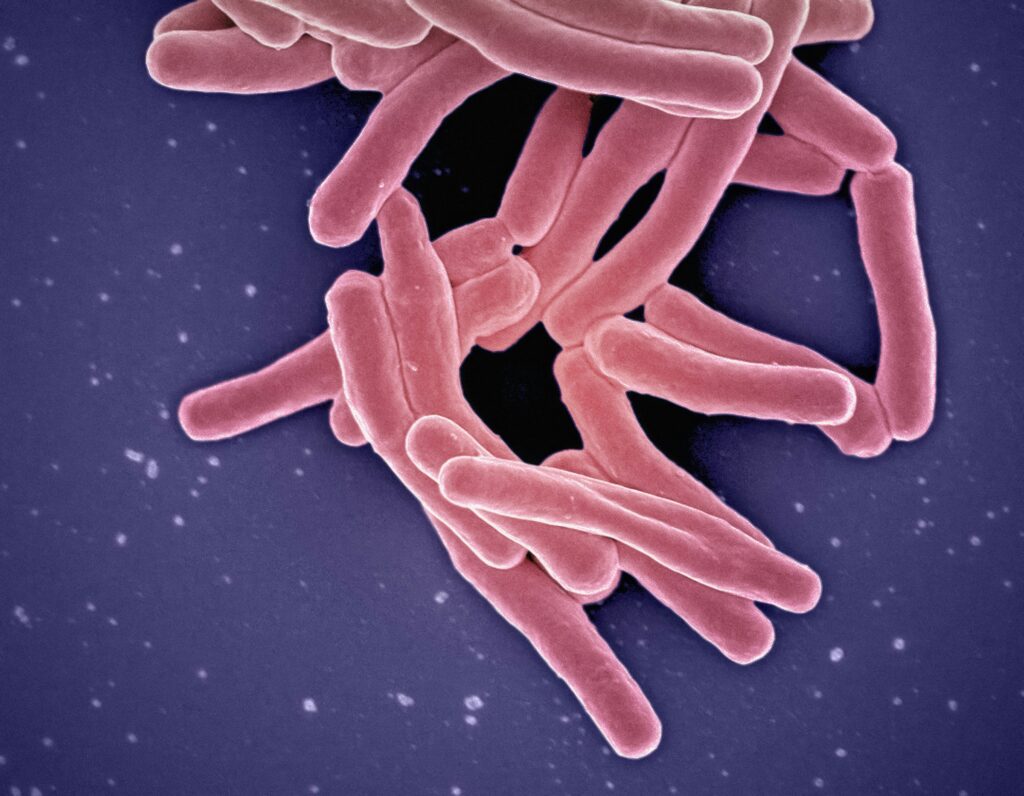

Staphylococcus Epidermidis: The Sweat Processor

Staphylococcus epidermidis is one of the most abundant bacterial species found on human skin, where it forms a significant part of our natural skin flora. This common bacterium feeds primarily on the components of sweat and sebum, helping to break down these substances on our skin surface. As it metabolizes sweat, S. epidermidis produces antimicrobial peptides that can inhibit the growth of more harmful bacteria, effectively serving as a first line of defense against potential pathogens. Research has shown that this bacterium also communicates with our immune system, helping to regulate inflammatory responses and maintain skin barrier function. The beneficial relationship between humans and S. epidermidis illustrates the concept of commensalism, where one organism benefits while the other is neither harmed nor significantly helped.

Corynebacterium: The Armpit Specialists

Corynebacterium species have adapted specifically to thrive in the unique microenvironment of human armpits and other moist, warm body areas with apocrine sweat glands. These rod-shaped bacteria metabolize the proteins and lipids found in apocrine sweat, which is odorless when first secreted but develops the characteristic “body odor” smell when processed by these microorganisms. While we might consider body odor unpleasant, the process serves important biological functions, including potential roles in immune defense and even unconscious social communication through pheromones. Different Corynebacterium species produce different odor profiles, which explains why body odor can vary significantly between individuals. Interestingly, these bacteria actually help prevent more offensive odors by outcompeting other microbes that might produce more pungent or unpleasant smells if allowed to dominate the armpit ecosystem.

Propionibacterium Acnes: Oil Managers With a Bad Reputation

Recently renamed Cutibacterium acnes, this bacterium is often unfairly vilified due to its association with acne, but it actually plays several beneficial roles on healthy skin. P. acnes primarily inhabits sebaceous follicles, where it consumes sebum produced by the sebaceous glands, helping to regulate oil levels on the skin. Through its metabolic processes, this bacterium produces propionic acid, which maintains the skin’s acidic pH and inhibits the growth of many pathogenic microorganisms. Research has revealed that P. acnes also produces bacteriocins, which are natural antibiotics that target potentially harmful bacteria. The relationship with P. acnes becomes problematic only when factors like hormonal changes, excessive sebum production, or altered skin cell turnover create conditions that allow these normally beneficial bacteria to proliferate beyond healthy levels.

Mites in Your Mattress: The Dust Dwellers

House dust mites (Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus and Dermatophagoides farinae) aren’t directly living on our bodies, but they’ve evolved to thrive in our immediate environment, particularly our bedding, where they feed primarily on the dead skin cells we shed. The average person sheds about 1.5 grams of skin daily—enough to feed millions of these microscopic arachnids that measure just 0.3 millimeters in length. A typical mattress can harbor anywhere from 100,000 to 10 million dust mites, creating a veritable ecosystem in the place where we spend approximately one-third of our lives. While dust mites don’t bite or transmit diseases, their waste products and body fragments contain proteins that can trigger allergic reactions in sensitive individuals, leading to symptoms ranging from sneezing and itchy eyes to more severe asthmatic responses.

The Gut Microbiome: Internal Waste Processors

Moving inside the body, our gastrointestinal tract hosts the largest and most diverse population of microorganisms in our personal ecosystem, with bacteria comprising the majority of these residents. These gut bacteria perform crucial digestive functions by breaking down food components that human enzymes cannot process, particularly complex carbohydrates like dietary fiber. Through fermentation, gut bacteria transform these indigestible materials into short-chain fatty acids that nourish colon cells and regulate immune function. Beyond digestion, the gut microbiome synthesizes essential vitamins including K2, B12, thiamine, and riboflavin, which the body cannot produce independently. Research increasingly links the composition of the gut microbiome to numerous aspects of health, including immune function, mental health, metabolism, and even longevity, highlighting the profound importance of these internal “waste processors.”

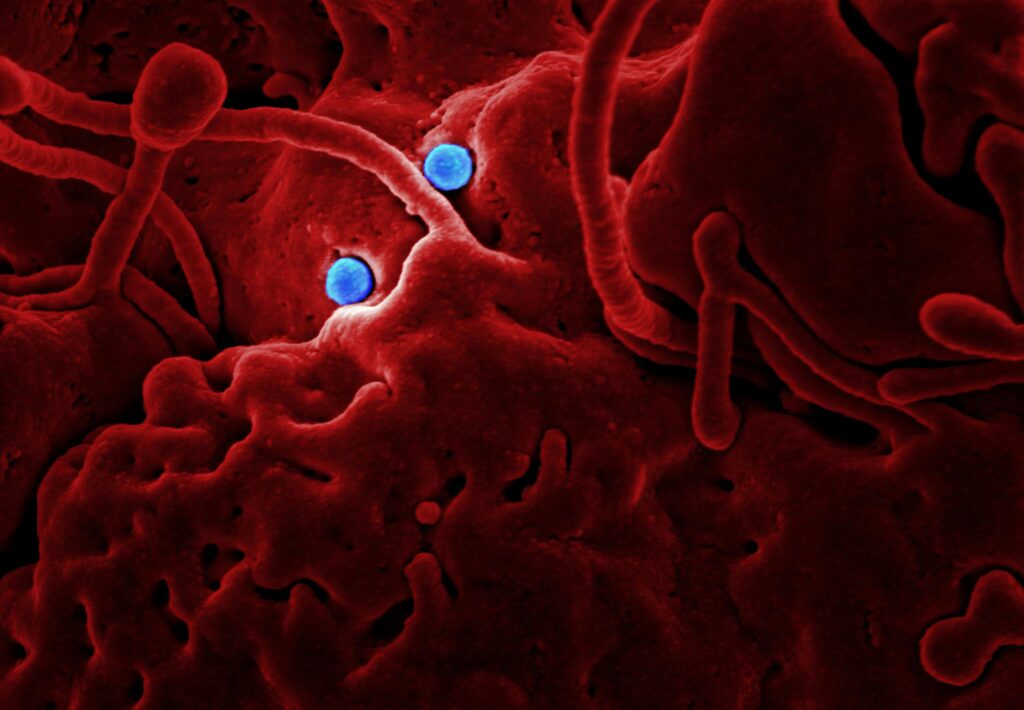

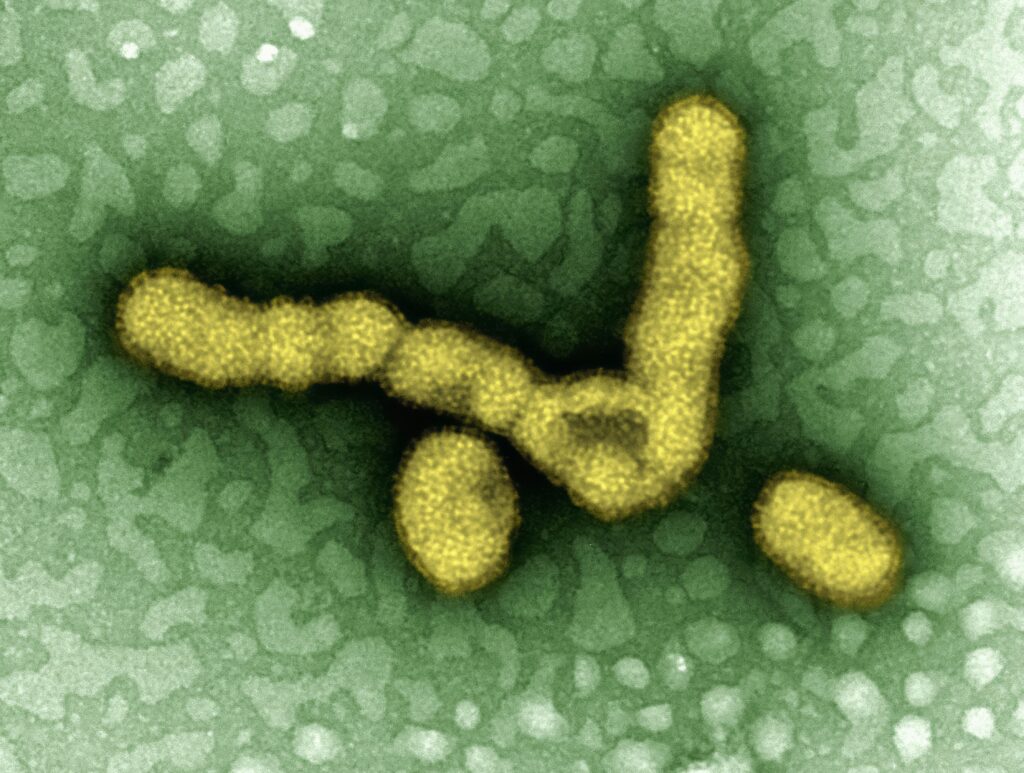

Bacteriophages: The Bacteria Eaters

Bacteriophages, or phages for short, are viruses that specifically infect and replicate within bacteria, effectively serving as “bacteria eaters” that help regulate bacterial populations throughout the human microbiome. These nanoscopic entities are astoundingly abundant on and within our bodies, with estimates suggesting there are 10 phages for every bacterial cell in the human microbiome. While not technically consuming our bodily waste, phages perform the vital function of controlling bacterial populations, including those that process our dead skin, sweat, and oils. Researchers are increasingly recognizing the crucial role of the “phageome” in maintaining microbiome health and preventing dysbiosis—imbalances in bacterial communities that can lead to disease. The highly specific nature of phages, with most targeting only particular bacterial species or strains, allows for exquisite fine-tuning of bacterial populations across different body sites.

The Oral Microbiome: Saliva and Food Residue Specialists

The human mouth hosts over 700 species of bacteria that form a complex ecosystem adapted to the unique environment of our oral cavity. Many of these microorganisms feed on food particles left between teeth and along the gumline, as well as components in saliva and shed oral epithelial cells. Streptococcus salivarius, one of the first bacterial species to colonize the mouth in infants, helps prevent colonization by pathogenic bacteria through competitive exclusion and by producing antimicrobial compounds. Other beneficial oral bacteria break down food residues that might otherwise feed harmful species associated with tooth decay and gum disease. Some oral bacteria even help neutralize acidic compounds that could damage tooth enamel, demonstrating how these microorganisms contribute to maintaining oral health when properly balanced.

Disrupted Microbiomes: When The Balance Tips

Despite their crucial roles in maintaining our health, the delicate balance of our microbial communities can be disrupted by modern lifestyle factors, often with negative consequences. Overuse of antibiotics, while sometimes necessary to treat bacterial infections, can indiscriminately eliminate beneficial microorganisms alongside pathogens, potentially leading to conditions ranging from antibiotic-associated diarrhea to increased vulnerability to pathogen colonization. Excessive hygiene practices, including frequent use of antimicrobial soaps and sanitizers, can similarly disrupt skin microbiomes, potentially contributing to increased incidence of allergic and inflammatory skin conditions. Highly processed diets low in fiber deprive gut bacteria of their preferred food sources, potentially leading to decreased microbial diversity and associated health problems. Chronic stress, environmental pollutants, and certain medications can further disrupt these microbial communities, highlighting the importance of supporting rather than fighting our microbial partners.

Nurturing Your Microscopic Partners

Understanding the beneficial roles of our microbial inhabitants suggests approaches to personal hygiene and health that support rather than suppress these important relationships. For skin microbiome health, dermatologists increasingly recommend gentle cleansing with non-antibacterial soaps, limiting hot water exposure that can strip natural oils, and using moisturizers that support the skin’s natural barrier function. Dietary approaches to support gut microbiome health include consuming diverse plant foods rich in prebiotic fibers, incorporating fermented foods containing live cultures, and limiting artificial sweeteners and emulsifiers that may disrupt microbial communities. Probiotic supplements may benefit some individuals, though effects are highly strain-specific and individual responses vary considerably. For oral microbiome health, regular but not excessive cleaning, limiting sugary foods and drinks, and staying hydrated to maintain saliva flow all contribute to a balanced oral ecosystem.

The Future of Microbiome Science

The science of the human microbiome remains in its relative infancy, with exciting developments emerging rapidly as research techniques advance. Next-generation sequencing technologies now allow scientists to identify and study microorganisms that cannot be cultured in laboratories, revealing previously unknown species and their functions. Emerging research areas include the development of precision probiotics designed to address specific health conditions, phage therapy as an alternative to antibiotics, and the potential for microbiome transplantation beyond the currently established fecal microbiota transplants used to treat recurrent Clostridium difficile infections. Scientists are also exploring the complex interactions between the microbiome and human genetics, seeking to understand how these factors combine to influence health and disease susceptibility. As our understanding deepens, we may eventually be able to precisely manipulate our microbiomes to treat or prevent a wide range of health conditions.

The microscopic creatures that consume our hair, skin, sweat, and other bodily products represent a fascinating frontier in our understanding of human health. Far from being disgusting parasites, these tiny organisms form an integral part of our biology, performing essential functions that our bodies cannot accomplish alone. The evolving science of the microbiome challenges us to reconsider our relationship with the microbial world—not as something to be universally feared and eliminated, but as a complex ecological partnership developed over millions of years of co-evolution. By better understanding and nurturing these relationships, we can potentially improve numerous aspects of our health while gaining a deeper appreciation for the remarkable complexity of our own bodies. Perhaps most profoundly, the science of the microbiome reminds us that we are never truly alone—we are walking ecosystems, home to trillions of microscopic companions that help keep us healthy, one dead skin cell at a time.