Spiders are among nature’s most successful predators, having evolved diverse hunting strategies over 380 million years. While venomous species often capture the spotlight, non-venomous spiders make up a significant portion of the 48,000+ spider species worldwide. These remarkable arachnids have developed fascinating alternative methods to capture prey without relying on venom. From engineering marvels of silk to ambush tactics that would impress military strategists, non-venomous spiders demonstrate nature’s incredible adaptability. This article explores the ingenious hunting techniques these eight-legged predators use to survive and thrive without the advantage of venom.

The Silent Engineers: Web-Building Fundamentals

Web-building represents perhaps the most recognizable spider hunting strategy, with non-venomous species perfecting this technique to remarkable degrees. These spiders produce specialized silk from their spinnerets—modified appendages containing numerous spigots connected to internal silk glands. The silk itself is a protein-based material that starts as liquid and solidifies upon contact with air, creating threads stronger than steel by weight. Non-venomous web-builders carefully design their snares to maximize efficiency, with some orb-weavers rebuilding intricate webs daily to ensure optimal prey-catching capabilities. The web serves not only as a physical trap but also as an extension of the spider’s sensory system, with vibrations traveling through the silk strands alerting the spider to the presence and location of potential meals.

Orb Weavers: Masters of Geometric Precision

Orb-weaving spiders, including many non-venomous species, create some of nature’s most visually striking hunting tools with their circular, wheel-shaped webs. These architectural marvels begin with a framework of non-sticky support strands radiating from a central hub, followed by a spiral of sticky capture silk. The sticky spiral contains glue droplets composed of complex glycoproteins that maintain their adhesive properties even in humid conditions, ensuring prey remains secured upon contact. Some orb weavers enhance their webs’ effectiveness by incorporating ultraviolet-reflective silk decorations called stabilimenta, which may attract insects or prevent birds from accidentally destroying the web. The spider typically waits at the hub or hides nearby, rushing out when vibrations indicate a trapped insect, then quickly wrapping the prey in silk before feeding.

Cobweb Spiders: The Chaotic Strategists

Unlike the orderly constructions of orb weavers, cobweb spiders (including many Theridiidae family members) create three-dimensional tangles of irregularly arranged threads that appear disorganized but are highly effective hunting tools. These webs feature strong supporting threads connected to surfaces and floors, with numerous sticky capture threads extending throughout the structure. A key innovation in many cobweb designs is the inclusion of vertical “trip lines” with glue droplets that collapse when disturbed, lifting struggling prey off surfaces and suspending them in midair. This strategy prevents insects from using ground leverage to escape and leaves them dangling helplessly until the spider arrives. Despite their chaotic appearance, these webs require less daily maintenance than orb webs while providing continuous prey-capturing capabilities in protected locations.

Sheet Web Weavers: The Ground Trappers

Sheet web weavers, including the Linyphiidae family, construct horizontal sheet-like webs that serve as platforms to intercept falling insects or those that bump into nearly invisible barrier threads stretched above. These barrier threads function as obstacles that cause flying insects to tumble onto the non-sticky sheet below, where they become temporarily disoriented. The spider, typically waiting upside-down beneath the sheet, detects the vibrations and quickly rushes to the upper surface to capture the confused prey. Many sheet web builders enhance their traps by incorporating dome-shaped structures or adding multiple layers that increase capture efficiency. These webs are particularly effective in grasslands and forest floors where they intercept insects dislodged from vegetation above.

Funnel Weavers: The Tunnel Ambushers

Funnel-weaving spiders, such as those in the Agelenidae family, construct sheet-like webs with a distinctive funnel-shaped retreat at one edge, creating a system that combines trap and shelter. The sheet portion is non-sticky but constructed with numerous fine threads that impede insect movement, causing them to stumble and struggle when crossing the surface. These vibrations alert the spider waiting in the funnel retreat, prompting it to rush out with remarkable speed to capture the prey before it can escape. The funnel design provides a quick escape route for the spider when threatened, allowing it to retreat deeper into the protected tunnel or exit through a rear entrance if necessary. Some funnel weavers enhance their webs’ effectiveness by building them in corners or against vegetation where insects naturally travel, increasing encounter rates.

Bolas Spiders: The Lasso Throwers

Among the most specialized non-venomous hunters are bolas spiders (Mastophora genus), which have abandoned traditional web-building in favor of a remarkable hunting technique using a specialized “bolas.” These clever arachnids create a single silk thread with a sticky globule at the end, which they swing at passing moths like a miniature lasso. Astonishingly, female bolas spiders can produce chemicals that mimic the sex pheromones of certain moth species, effectively luring male moths directly to them before capturing the attracted prey with their sticky weapon. The spider detects the approaching moth through air vibrations, times its swing perfectly, and reels in the captured prey after contact. This highly specialized technique allows these spiders to conserve energy and silk resources while targeting specific prey with remarkable precision.

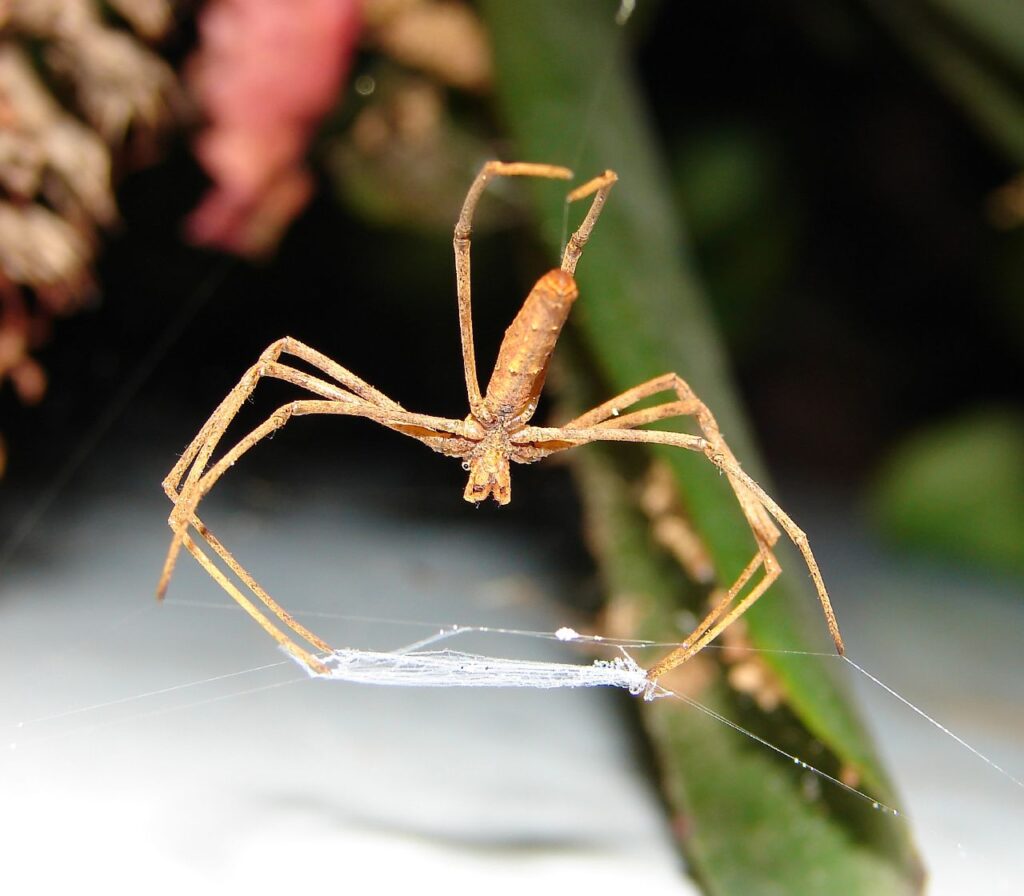

Net-Casting Spiders: The Aerial Trappers

Net-casting or ogre-faced spiders (Deinopidae family) demonstrate one of the most active hunting strategies among non-venomous spiders. These remarkable hunters construct small, rectangular “nets” of wooly, non-sticky silk held between their front legs while hanging upside-down from a silk line. With enormous eyes that gather light efficiently in darkness, the spider detects movement below, then rapidly stretches the net to several times its relaxed size and drops or lunges down to envelop the prey. The specialized capture silk is crinkly and covered with microscopic loops that entangle insect appendages without requiring adhesive properties. Some net-casters enhance their hunting by dangling directly above insect pathways or utilizing white patches of leaf debris below them that reflect moonlight and attract insects.

Jumping Spiders: The Calculating Predators

Jumping spiders (Salticidae family) represent the epitome of active hunting strategies among non-venomous spiders, relying on extraordinary vision, calculation, and athletic ability rather than webs. These charismatic hunters possess remarkably advanced eyes that provide both acute vision and depth perception, allowing them to locate prey from distances up to 20 cm away. After spotting potential prey, the jumping spider carefully stalks forward, anchoring a safety dragline silk thread as it moves, then calculates the precise distance and angle before leaping with remarkable accuracy. Their powerful legs can propel them up to 40 times their body length, landing directly on unsuspecting prey. Upon contact, jumping spiders quickly wrap their prey with silk before consuming it, demonstrating how effective hunting can be without venom or extensive web structures.

Crab Spiders: The Floral Ambushers

Crab spiders (Thomisidae family) employ perhaps the most patient hunting strategy among non-venomous spiders, relying on exceptional camouflage and ambush techniques. These sit-and-wait predators position themselves on flowers, often matching the flower’s color through physiological color changes that can range from white to yellow to pink depending on their surroundings. With their front legs extended crab-like to the sides, they remain motionless until pollinating insects land directly within reach. The spider then rapidly grabs the unsuspecting prey with powerful front legs equipped with microscopic structures that enhance gripping power. Some crab spider species can capture prey many times their size, including bees and butterflies, despite lacking venom to subdue their catch, demonstrating the effectiveness of precise ambush tactics and strong grasping appendages.

Silk Wrapping: The Universal Immobilization Technique

Regardless of their initial capture method, nearly all non-venomous spiders rely on silk wrapping as a critical technique for subduing and immobilizing prey without venom. Once prey is secured, the spider rapidly rotates it using its legs and pedipalps while simultaneously extruding silk from its spinnerets, creating a restrictive cocoon that prevents escape. This process typically begins with wide bands of silk to secure the larger body parts, followed by more precise wrapping of appendages and potential weapons like stingers or mandibles. Many species produce specialized wrapping silk that differs from web-building silk, being more efficient for quick immobilization rather than long-term structural integrity. The wrapped prey package not only prevents escape but also serves as a convenient food storage system that the spider can consume at leisure, sometimes after moving to a safer location.

Crushing Techniques: The Power of Chelicerae

When lacking venom to kill prey, many non-venomous spiders have developed particularly powerful chelicerae (jaws) and specialized feeding techniques to compensate. These spiders often possess stronger musculature in their chelicerae, allowing them to crush vital areas of their prey’s anatomy, particularly targeting the head or thorax regions where the central nervous system is located. The mechanical damage inflicted by repeated piercing and crushing actions effectively immobilizes prey even without chemical assistance. Some non-venomous species have evolved serrated edges on their chelicerae that enhance their ability to penetrate exoskeletons and tear tissue. Additionally, many species use their pedipalps (the leg-like appendages near the mouth) to manipulate prey precisely during the crushing process, ensuring efficient targeting of vulnerable areas.

Digestive Enzymes: External Digestion Without Venom

A fascinating aspect of all spider feeding, including non-venomous species, is their reliance on external digestion rather than traditional chewing. After securing prey through mechanical means, non-venomous spiders release digestive enzymes from their mouth onto the prey, effectively liquefying the internal tissues. This digestive fluid contains potent proteases, lipases, and other enzymes that break down proteins and tissues but differ from the neurotoxic components found in venoms. The spider then uses its powerful sucking stomach to draw in the liquefied nutrients, leaving behind an empty exoskeleton. This external digestion system allows even small spiders to consume prey larger than themselves by processing it in manageable portions. Some non-venomous species have evolved particularly potent digestive enzymes to compensate for their lack of venom, enabling faster immobilization and consumption of prey.

Evolutionary Advantages of Non-Venomous Hunting

While venom might seem like an obvious evolutionary advantage, non-venomous hunting strategies offer several benefits that have allowed these spiders to thrive alongside their venomous relatives. Non-venomous methods often require less metabolic energy than producing complex venom proteins, redirecting those resources toward producing more silk, developing specialized sensory systems, or increasing reproductive output. Many non-venomous species can exploit niches unavailable to venomous ambush hunters, such as aerial interception or specialized habitats where their particular capture methods excel. The diversity of non-venomous hunting techniques also promotes coexistence of multiple spider species in the same habitat by reducing direct competition, as different hunting strategies target different prey types or the same prey in different ways. Additionally, the absence of venom production may allow for faster development and maturation in some species, providing competitive advantages in rapidly changing environments or seasonal habitats.

Conclusion

The remarkable diversity of hunting strategies employed by non-venomous spiders showcases nature’s ingenuity in evolving solutions to the fundamental challenge of capturing prey. From the geometric precision of orb weavers to the calculated pounces of jumping spiders, these arachnids demonstrate that effective predation doesn’t necessarily require venom. Their success lies in specialization—developing extraordinary silk technologies, sensory capabilities, physical adaptations, and behavioral strategies that compensate for the lack of chemical weapons. As we continue to study these fascinating creatures, we discover not only the incredible diversity of their hunting methods but also valuable insights into biomaterials, sensory processing, and efficient design principles that may inspire human innovations. Non-venomous spiders remind us that in the evolutionary arms race, there are many paths to success beyond the most obvious solutions.