Beneath our feet and often beyond our notice, a remarkable cleanup operation has been underway for hundreds of millions of years. Insects, Earth’s most abundant and diverse group of animals, have been quietly serving as nature’s sanitation workers since long before humans appeared on the planet. From decomposing dead organisms to recycling waste and controlling populations of other species, these tiny creatures perform ecosystem services that keep our world balanced and habitable. Their collective impact is so profound that without their constant labor, we would be living on a very different—and likely uninhabitable—planet. This article explores the fascinating ways insects have been cleaning up Earth and maintaining ecological balance through the ages, highlighting their critical yet often underappreciated role in the planet’s health.

The Ancient Origins of Insect Cleanup Crews

Insects first appeared in the fossil record approximately 400 million years ago during the Devonian period, though scientists believe they may have evolved even earlier. By the Carboniferous period (359-299 million years ago), diverse insect communities were already performing vital ecological services. Early insects evolved alongside the first land plants, developing specialized mouthparts and digestive systems to break down plant material. Fossil evidence shows that these ancient cleanup crews were already processing dead organic matter, recycling nutrients, and aerating soils long before dinosaurs walked the Earth. This long evolutionary history has allowed insects to fine-tune their cleanup abilities, creating the remarkably efficient systems we observe today.

Nature’s Most Efficient Decomposers

Among the most important ecological roles insects play is that of decomposers, breaking down dead plants and animals and returning their nutrients to the soil. Beetles in the family Silphidae, commonly known as carrion beetles, specialize in locating and consuming dead animals, sometimes detecting a carcass from miles away within hours of death. Blow flies quickly lay eggs on fresh carrion, and their larvae (maggots) can consume up to 60% of a carcass in less than a week. This rapid decomposition prevents the buildup of dead matter, limits the spread of diseases, and accelerates nutrient cycling in ecosystems. Without these insect decomposers, dead organisms would accumulate on Earth’s surface, creating unsanitary conditions and locking away nutrients needed for new life.

Dung Beetles: Ancient Waste Management Experts

Dung beetles represent one of nature’s most remarkable waste management systems, having evolved alongside mammals to process their waste efficiently. These industrious insects can detect fresh dung from remarkable distances, then quickly roll it into balls, bury it, or shape it into brood chambers for their offspring. A single pair of African dung beetles can bury dung 250 times their own weight in one night, removing it from the surface where it would otherwise breed flies and parasites. Paleontological evidence suggests dung beetles have been performing this service since the Mesozoic Era, helping process dinosaur dung before transitioning to mammalian waste. Their activity aerates soil, cycles nutrients, disperses seeds found in mammal dung, and significantly reduces greenhouse gas emissions that would otherwise occur during natural dung decomposition.

Termites: Earth’s Original Recyclers

Termites represent one of the most effective cellulose recycling systems on the planet, breaking down dead wood and plant material that few other organisms can digest. These social insects have specialized gut microbes that produce enzymes capable of breaking down cellulose and lignin, the tough structural components of plant cell walls. Termite activity returns carbon locked in dead trees back to the soil, completing a crucial link in the carbon cycle. In tropical and subtropical ecosystems, termites process more dead wood than any other organism, with some estimates suggesting they recycle up to one-third of annual dead wood production in these regions. Their constant tunneling also aerates and mixes soil layers, improving soil structure and fertility much like earthworms do in temperate climates.

Aquatic Insects: Underwater Cleanup Specialists

Freshwater ecosystems benefit from their own insect cleanup crews that help maintain water quality and process organic matter. Caddisfly larvae, mayfly nymphs, and other aquatic insects feed on decaying leaves and other detritus that falls into streams and ponds, preventing the buildup of organic material that could deplete oxygen levels. Many filter-feeding aquatic insects strain tiny particles from the water, essentially serving as living water purifiers. Dragonfly and damselfly nymphs are voracious predators that help control populations of mosquito larvae and other potential pest species in aquatic habitats. These underwater cleanup specialists have been performing these ecological services for hundreds of millions of years, helping maintain the health of Earth’s freshwater systems long before humans began worrying about water quality.

Pollinator Cleanup: Beyond Honey Production

While we often think of pollinating insects primarily for their role in plant reproduction, this activity also represents a form of ecological cleaning. When bees, butterflies, and other pollinating insects visit flowers, they remove excess pollen that might otherwise accumulate and potentially foster fungal growth. Their constant grooming behaviors help reduce the spread of plant pathogens by removing spores along with pollen from their bodies. Fossil evidence indicates insects have been pollinating plants for at least 100 million years, co-evolving with flowering plants to create the diverse ecosystems we see today. This ancient partnership between insects and plants has helped maintain plant community health while simultaneously ensuring the insects’ own survival through access to nectar and pollen resources.

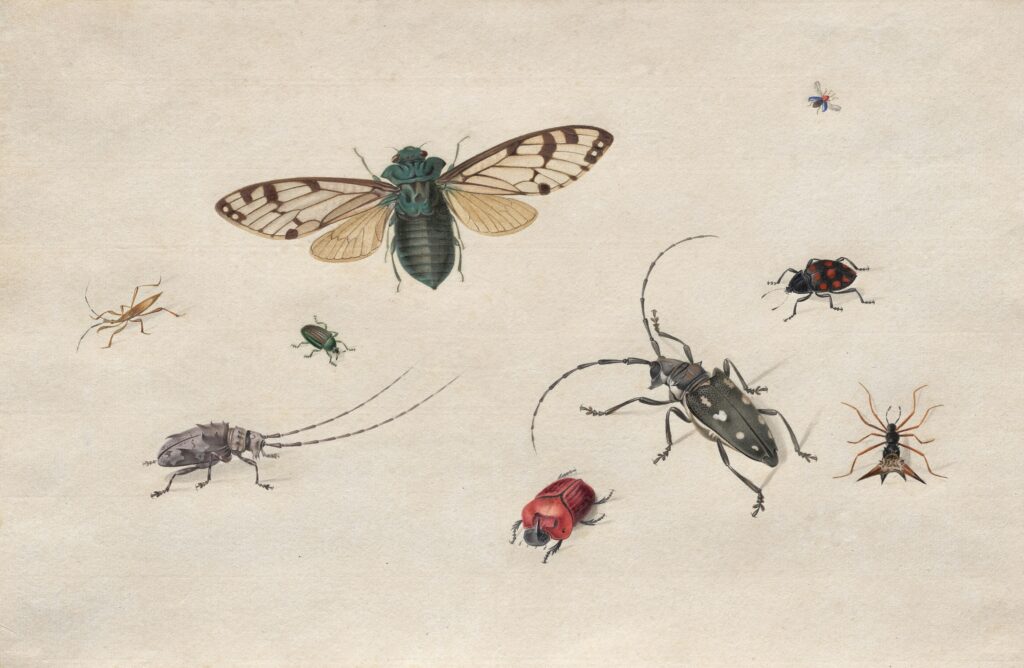

Predatory Insects: Nature’s Population Controllers

Predatory insects perform critical cleanup services by controlling populations of other arthropods, preventing potentially destructive outbreaks. Ladybugs (lady beetles) can consume up to 5,000 aphids in their lifetime, helping protect plants from these sap-sucking pests. Praying mantises are ambush predators that capture and consume a wide variety of insects, helping maintain balance in garden and field ecosystems. Predatory wasps not only hunt other insects but often parasitize them, laying eggs inside hosts whose bodies become food for developing wasp larvae. These predator-prey relationships have evolved over millions of years, creating natural checks and balances that prevent any single species from dominating an ecosystem and potentially causing damage through unchecked population growth.

Soil Engineers: Improving Earth’s Foundation

Countless insects spend part or all of their lives in soil, where they contribute significantly to soil health and formation. Ants move enormous amounts of soil during nest construction, bringing deeper minerals to the surface and creating channels that improve water infiltration and root growth. Cicada nymphs spend years underground, slowly processing organic matter and creating air spaces in the soil before emerging as adults. Beetle larvae of many species burrow through soil, breaking down organic particles and mixing soil layers in ways that improve fertility. Collectively, soil-dwelling insects process billions of tons of soil annually across the globe, helping create and maintain the fertile foundation that supports terrestrial life.

Insects as Nature’s Undertakers

Before modern funeral practices, insects served as nature’s undertakers, efficiently processing the remains of deceased organisms. Specialized necrophagous (corpse-eating) insects arrive at a dead body in predictable waves, a process forensic entomologists now use to determine time since death in criminal investigations. First come the blow flies and flesh flies, followed by beetles like hide beetles and clown beetles, with finally moth larvae and mites cleaning up the remaining dried tissues. This succession ensures complete decomposition and nutrient recycling, preventing the accumulation of corpses that could spread disease. Without these natural undertakers, ecosystems would quickly become overloaded with the remains of the billions of organisms that die naturally each year.

Desert and Harsh Environment Cleanup Crews

Even in Earth’s harshest environments, specialized insects persist as cleanup specialists, processing scarce organic resources with remarkable efficiency. Desert-dwelling darkling beetles collect moisture from fog while scavenging for dead plant and animal matter that would otherwise accumulate in these arid ecosystems. Tenebrionid beetles in the Namib Desert have evolved specialized water-collecting structures on their bodies, allowing them to survive while continuing to process organic detritus. In polar regions, springtails and mites break down the limited organic material, ensuring nutrient cycling despite the harsh conditions. These extremophile insects demonstrate the remarkable adaptability of the insect cleanup crews, which have evolved to maintain their ecological services even in the planet’s most challenging environments.

Human Exploitation of Insect Cleanup Services

Humans have increasingly recognized and harnessed the cleaning power of insects for our own purposes. Medical professionals use maggot therapy (applying sterilized fly larvae to wounds) to remove dead tissue and prevent infection in cases where traditional treatments fail. Forensic entomologists study insect succession on human remains to solve crimes by determining time and sometimes place of death. Black soldier fly larvae are being cultivated to process food waste and produce protein-rich feed for livestock, potentially revolutionizing waste management. Increasingly, environmental engineers are designing “insect bioreactors” that use beetles, flies, and other insects to process specific waste streams or pollutants, mimicking and accelerating the natural cleanup processes these organisms have performed for millions of years.

Threats to Earth’s Insect Cleaning Crews

Despite their crucial ecological roles, insect populations worldwide face unprecedented threats that could disrupt their ancient cleanup services. Widespread insecticide use, habitat destruction, light pollution, climate change, and invasive species have all contributed to what some scientists call the “insect apocalypse,” with studies showing alarming declines in insect abundance and diversity. The loss of pollinator species has received considerable attention, but equally concerning is the potential disruption to decomposition, waste processing, and other cleaning services that less charismatic insects provide. Ecosystem functionality depends on these insects continuing their work, yet many species are disappearing before scientists can even document their ecological roles. Protecting Earth’s insect cleaning crews requires addressing these threats through conservation efforts, reduced pesticide use, habitat preservation, and greater appreciation for these essential but often overlooked organisms.

Conclusion: Recognizing Nature’s Tiniest Janitors

For hundreds of millions of years, insects have been Earth’s most dedicated environmental stewards, recycling waste, processing dead materials, maintaining soil health, and preventing any single species from dominating ecosystems. Their cleaning services laid the groundwork for the development of complex ecosystems long before humans appeared, and they continue this vital work today largely unnoticed and unappreciated. As we face mounting environmental challenges, from waste management to carbon sequestration, we would do well to study and protect these tiny janitors that have been sustainably cleaning our planet since the Paleozoic Era. By recognizing the essential ecosystem services that insects provide, we gain not only a deeper appreciation for these fascinating creatures but also potential inspiration for solving our own environmental challenges through biomimicry and conservation of nature’s most successful cleanup specialists.