The emerald ash borer, a deceptively beautiful metallic green beetle no larger than a penny, has carved a path of unprecedented destruction across North America’s ash trees. First discovered in Michigan in 2002, this invasive insect has transformed from an unknown Asian species to one of the most devastating forest pests in U.S. history. Its journey spans continents and cultures, representing a cautionary tale about global trade, ecosystem vulnerability, and the unintended consequences of human activity. As this beetle continues its relentless spread from the Great Lakes to the Appalachian forests and beyond, it leaves scientists, conservationists, and communities scrambling to understand and address its impact on American landscapes and economies.

The Native Habitat and Biology of the Emerald Ash Borer

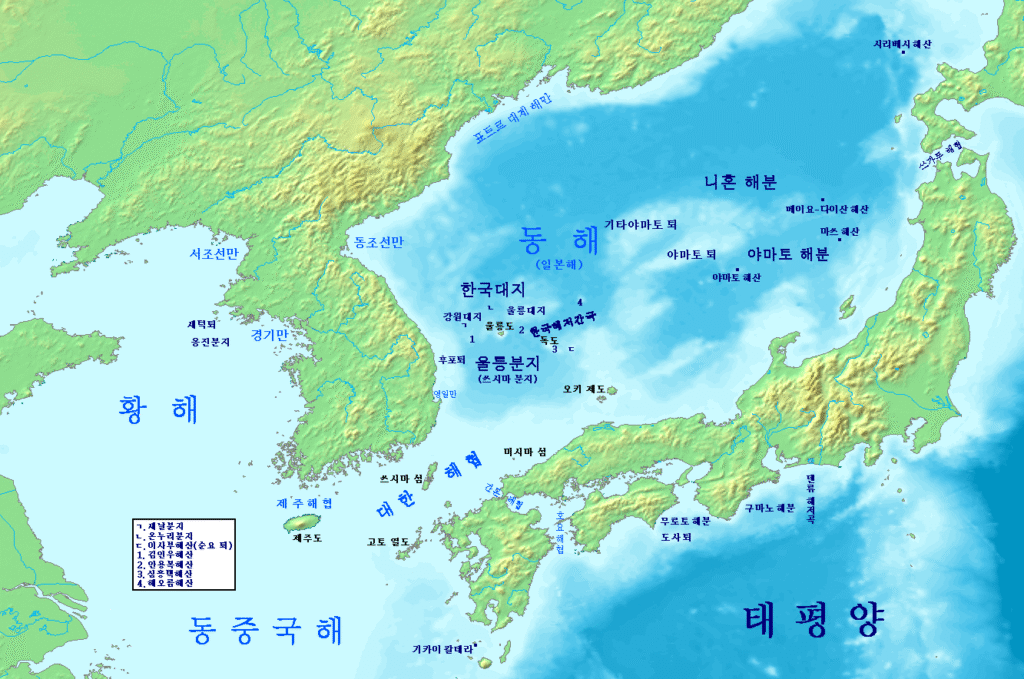

The emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis) evolved in the temperate forests of northeastern Asia, primarily across parts of China, Japan, Korea, and eastern Russia. In these native regions, the beetle exists in relative harmony with Asian ash species, which have co-evolved defensive mechanisms against the insect over thousands of years. Adult beetles measure about 8.5-14mm in length, displaying a distinctive metallic emerald green coloration that inspired their common name. Their life cycle spans one to two years depending on climate conditions, with adults emerging in spring to feed briefly on ash foliage before mating and laying eggs in bark crevices. The true damage occurs during the larval stage, when the developing insects create serpentine tunnels called galleries beneath the bark, effectively cutting off the tree’s nutrient and water transport systems.

The Accidental Introduction to North America

The emerald ash borer’s arrival in North America represents a classic case of unintended biological invasion through global commerce. Most experts believe the beetle arrived in solid wood packing materials—likely wooden crates or pallets—used to ship goods from Asia to the United States in the 1990s. The exact timing remains uncertain, but researchers estimate the beetle may have been present for 5-10 years before its official discovery in southeastern Michigan in June 2002. Initially, officials mistakenly believed the infestation was localized and potentially containable, not yet understanding the beetle had already established multiple breeding populations across Michigan and neighboring Ontario, Canada. This detection delay proved catastrophic, allowing the insect to gain a significant foothold before any control measures could be implemented.

Why North American Ash Trees Are Vulnerable

North American ash species have proven exceptionally vulnerable to emerald ash borer attack due to their evolutionary naïveté—they simply never developed the necessary defense mechanisms against this particular pest. Unlike their Asian counterparts, which co-evolved with the beetle and developed chemical and physical defenses, North American ash trees like white ash (Fraxinus americana), green ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica), and black ash (Fraxinus nigra) have minimal resistance. This vulnerability is compounded by the beetle’s behavior in North America, where it attacks trees of all sizes and health conditions, not just stressed or weakened specimens as it typically does in its native range. Mortality rates in infested areas regularly exceed 99%, with trees typically dying within 2-5 years of initial infestation. This unprecedented susceptibility has allowed the emerald ash borer to spread more rapidly and cause more extensive damage than initially predicted.

The Spread Across Eastern North America

Following its discovery in Michigan, the emerald ash borer began an inexorable expansion across eastern North America that continues today. The beetle can naturally spread about 1-2 miles annually through adult flight, but human-assisted movement—primarily through transported firewood, nursery stock, and timber products—has accelerated its range expansion by hundreds of miles in single jumps. By 2010, the beetle had been confirmed in 15 states and two Canadian provinces; today, it inhabits 36 states and five provinces, with the front of infestation having reached the Rocky Mountains to the west and deep into the southeastern United States. The progression into Appalachia began around 2007-2008, with confirmations in Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and eventually Virginia, Tennessee, Kentucky, and the Carolinas. This rapid spread occurred despite numerous quarantines and public awareness campaigns designed to limit human-assisted transport.

Ecological Impacts on Forest Ecosystems

The emerald ash borer’s impact extends far beyond the loss of individual trees, triggering cascading ecological effects throughout forest ecosystems. Ash trees serve as foundational species in many forest communities, particularly in riparian areas and wetlands where they help regulate water cycles, prevent erosion, and provide crucial habitat structure. Their sudden disappearance creates canopy gaps that alter light conditions, soil moisture, and temperature regimes, potentially facilitating the spread of invasive plant species that thrive in disturbed environments. Research has documented significant impacts on forest-dwelling wildlife, with over 280 arthropod species associated with ash trees facing potential population declines or local extinctions. Particularly vulnerable are specialized insects that feed exclusively on ash, as well as woodpeckers and other birds that nest in ash trees or feed on ash-dependent insects.

Cultural and Economic Significance in Appalachia

In Appalachia, ash trees hold both economic and cultural significance that magnifies the impact of emerald ash borer infestations. White ash has traditionally been prized for its strength and flexibility, making it the preferred wood for tool handles, baseball bats, furniture, flooring, and musical instruments throughout the region. The loss of ash presents an economic blow to the timber industry, with estimates suggesting emerald ash borer damage will cost communities $12.7 billion by 2020. Beyond commercial value, ash trees feature prominently in Appalachian folk traditions and craft heritage, particularly in Cherokee and other Native American basketry, where black ash has been an irreplaceable material for generations. Many mountain communities have witnessed the decline of trees that have stood for generations, altering familiar landscapes and severing living connections to cultural practices.

Scientific Detection and Monitoring Methods

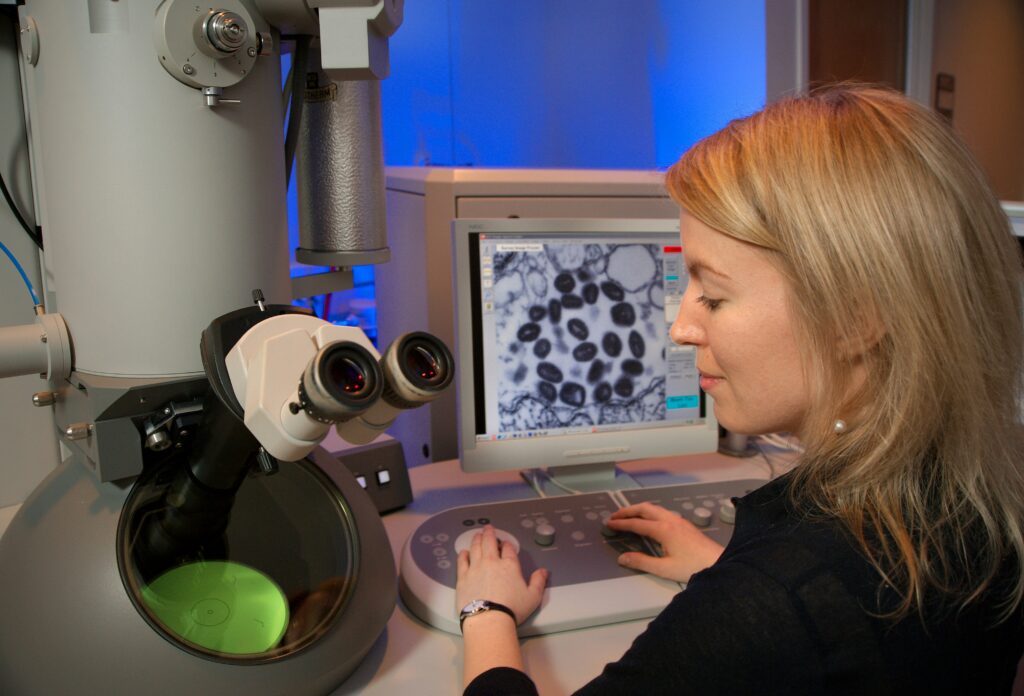

As the emerald ash borer continued its spread, scientists developed increasingly sophisticated methods to detect and monitor infestations. Early detection systems include visual surveys for adult beetles, larval galleries, and characteristic D-shaped exit holes left when adults emerge from trees. Purple prism traps—sticky triangular boxes baited with compounds that mimic stressed ash volatiles—have become ubiquitous in monitoring programs, though they’re most effective when beetle populations are already relatively high. More sensitive detection methods include branch sampling (removing and peeling bark from branches to check for larvae) and biosurveillance using native predator wasps that hunt the beetles. The most recent advances involve acoustic monitoring to detect larval feeding sounds inside trees and environmental DNA sampling to identify beetle presence from environmental samples.

Management Strategies and Control Efforts

Management approaches for emerald ash borer have evolved from early eradication attempts to more nuanced integrated pest management strategies. Chemical treatments using systemic insecticides can protect individual high-value trees in urban and landscape settings, though they require regular reapplication and are not economically feasible for forest-scale protection. Biological control shows promising results through the careful introduction of specialized parasitoid wasps from the beetle’s native range, which target and kill emerald ash borer eggs and larvae. These natural enemies, including Tetrastichus planipennisi, Oobius agrili, and Spathius galinae, have established successfully in many release areas and reduced beetle populations locally, though they cannot eliminate the pest entirely. Researchers are also investigating genetic approaches, including breeding resistant ash varieties and potentially using gene editing technologies to enhance native ash resistance.

Adaptation and Resistance in Ash Populations

Despite the overwhelming mortality rates, small numbers of ash trees have survived even in heavily infested areas, offering a glimmer of hope for the genus’s future. Researchers are studying these “lingering ash” survivors to identify potential genetic traits conferring natural resistance. Some trees appear to mount stronger defensive responses to attack, producing compounds that deter beetle feeding or impede larval development. Ongoing work at the USDA Forest Service and several universities focuses on breeding these resistant individuals and developing propagation methods to restore ash to affected landscapes. Early research suggests resistance may involve multiple genetic factors and complex interactions with environmental conditions. Though promising, experts caution that developing and deploying resistant ash populations will take decades, and complete restoration to pre-infestation levels is unlikely within our lifetimes.

The Role of Community Response in Appalachia

Across Appalachia, communities have mounted creative responses to the emerald ash borer crisis that balance scientific intervention with local needs and values. Urban forestry programs in cities like Knoxville, Tennessee and Asheville, North Carolina have implemented strategic management plans that prioritize treatment of high-value trees while planning for structured removal and replacement of others. Many mountain communities have established wood utilization programs that salvage ash trees before or shortly after death, converting potential waste into valuable lumber, art, or energy products. Educational initiatives through cooperative extension services, master naturalist programs, and forest health workshops have empowered landowners with knowledge to identify and respond to infestations on their properties. Perhaps most poignantly, cultural preservation efforts have emerged to document traditional ash-based crafts and identify alternative materials that might sustain these practices into the future.

Lessons for Invasive Species Management

The emerald ash borer invasion offers crucial lessons for preventing and managing future biological invasions. The case highlights the critical importance of early detection and rapid response systems that can identify new invasive species before they become established. Regulatory agencies have strengthened inspection protocols for imported wood products and packing materials, though gaps in the system remain. The experience has demonstrated the value of international cooperation in invasive species management, as scientists from the United States and the beetle’s native range collaborated to understand its biology and identify natural enemies. Perhaps most significantly, the emerald ash borer has raised public awareness about the risks of moving firewood and other untreated wood products, with “Don’t Move Firewood” becoming one of the most successful invasive species messaging campaigns in North American history.

Future Trajectories and Research Frontiers

As the emerald ash borer continues its expansion, researchers are exploring numerous frontiers to mitigate its impacts and prevent similar invasions. Cutting-edge genetic technologies, including CRISPR gene editing, offer potential pathways to enhance ash resistance, though significant ecological and ethical questions surround such approaches. Scientists are investigating how climate change might influence beetle population dynamics and spread patterns, with some models suggesting warming temperatures could accelerate life cycles and invasion rates in previously marginal habitats. Ecological research focuses on understanding forest succession patterns after ash loss, with particular attention to whether native or invasive species will fill canopy gaps. There’s also growing interest in the evolutionary dynamics of the invasion, as both the beetle and surviving ash trees potentially adapt to their new relationship, potentially reaching a less destructive equilibrium over evolutionary time.

The Emerald Ash Borer in Global Context

While North America grapples with the emerald ash borer, the beetle has also been discovered in European Russia (2003), Ukraine (2019), and continues to spread westward toward central Europe. This transcontinental expansion places the emerald ash borer among the most significant forest pests globally, joining other notorious invasives like the Asian longhorned beetle, sudden oak death pathogen, and hemlock woolly adelgid. Together, these invasions reflect the increasing ecological homogenization driven by global trade and human movement. Each year, scientists identify approximately 2,500 non-native insect species in international cargo, highlighting the ongoing risk of new invasions. The emerald ash borer story reminds us that in our interconnected world, ecological threats no longer remain contained within their native ranges, and effective biosecurity requires international cooperation, vigilance, and sustained investment in prevention and early detection systems.

Conclusion

The emerald ash borer’s journey from Asia to Appalachia represents one of the most consequential biological invasions in recent history. As this metallic green beetle continues reshaping North American forests, it leaves behind valuable if painful lessons about global trade, ecosystem vulnerability, and human responsibility. While the loss of ash trees has been devastating, the response has demonstrated remarkable scientific ingenuity and community resilience. From sophisticated biological control programs to grassroots wood utilization initiatives, humans are adapting to this new ecological reality. The full story of the emerald ash borer is still unfolding, with both concerning expansions and promising breakthroughs continuing to emerge. What remains certain is that this tiny beetle has permanently altered our forests and our relationship with them, serving as a powerful reminder that in our globalized world, ecological stewardship must extend beyond political boundaries to embrace the interconnected nature of our planet’s living systems.