The human body is never truly alone. Beyond the cells that make up our tissues and organs, we host an astonishing ecosystem of microscopic organisms that call our skin, hair, and bodily surfaces home. While the thought of tiny bugs living on us might initially trigger discomfort, this microcosm tells a fascinating story about evolution, symbiosis, and the intricate balance of nature. From the demodex mites nestled in our follicles to the bacteria forming protective colonies across our skin, these minute passengers influence our health in ways scientists are only beginning to understand. This article explores the surprisingly complex world of our body’s smallest inhabitants, revealing how these creatures shape our wellness, immunity, and even our understanding of what it means to be human in a microbial world.

The Skin Microbiome: A Bustling Ecosystem

Your skin, the body’s largest organ, hosts approximately 1.5 trillion bacteria spanning more than 1,000 different species. This diverse community forms what scientists call the skin microbiome—a protective layer that functions as your body’s first line of defense against harmful invaders. These microorganisms aren’t merely passive passengers; they actively produce antimicrobial substances that inhibit the growth of dangerous pathogens. The composition of your microbiome is unique as a fingerprint, influenced by factors including genetics, diet, environment, and even the skincare products you use. Recent research suggests this bacterial ecosystem plays crucial roles not only in skin health but also in immune function, inflammation regulation, and potentially even mood and behavior through the skin-brain axis.

Demodex Mites: The Facial Follicle Dwellers

Virtually every adult human hosts demodex mites—microscopic eight-legged arachnids that particularly favor hair follicles and sebaceous glands around the nose, eyebrows, and eyelashes. Two species primarily colonize humans: Demodex folliculorum, which lives in hair follicles, and Demodex brevis, which prefers sebaceous glands. These transparent creatures, measuring between 0.1 and 0.4 millimeters, spend their entire lifecycle on human hosts, emerging mainly at night to mate and move across the skin’s surface. Contrary to common misconceptions, the presence of these mites is entirely normal and typically harmless, with the average person hosting thousands without any negative effects. However, abnormally large populations can sometimes contribute to skin conditions like rosacea or blepharitis, particularly in people with compromised immune systems.

Head Lice: Persistent Parasites with Historical Significance

Head lice (Pediculus humanus capitis) have been unwelcome companions to humans throughout recorded history, with evidence of their presence dating back to ancient Egyptian mummies. These wingless insects measure 2-3 millimeters long and feed exclusively on human blood, attaching their eggs (nits) firmly to hair shafts near the scalp. Unlike some other body hitchhikers, lice require direct head-to-head contact to spread, making them particularly common among school-aged children. Despite popular belief, lice infestations have nothing to do with personal hygiene—they thrive equally well on clean or unwashed hair. Evolutionary research suggests humans and lice have co-evolved for millions of years, with genetic studies of lice populations providing insights into human migration patterns and even confirming when humans began wearing clothes.

Dust Mites: The Bedtime Companions

Dust mites aren’t technically on your body, but they share your most intimate spaces—your bed, pillows, and furniture—feeding primarily on the dead skin cells you shed. The average person sheds up to 1.5 grams of skin daily, providing an abundant food source for these microscopic arachnids that measure just 0.25-0.3 millimeters. A typical mattress can harbor between 100,000 to 10 million dust mites, invisible to the naked eye yet significant in their impact on human health. For many people, dust mite allergies rank among the most common triggers of year-round allergies and asthma, with symptoms caused not by the mites themselves but by their waste products and decomposing bodies. Climate change researchers have noted concerning trends showing extended breeding seasons for dust mites in many regions, potentially worsening their health impacts in coming decades.

Beneficial Bacteria: Your Skin’s Protective Shield

Not all microorganisms on your body deserve vilification—many bacterial species play vital protective roles that benefit human health. Staphylococcus epidermidis, one of the most abundant bacteria on human skin, helps prevent colonization by more dangerous pathogens like Staphylococcus aureus by competing for resources and producing antimicrobial peptides. Propionibacterium acnes, despite its association with acne when imbalanced, normally helps maintain skin pH and produces fatty acids that inhibit other harmful microbes. Corynebacterium species contribute to body odor but also help maintain the acidic environment that discourages pathogen growth. Research into these beneficial relationships has inspired new approaches to skincare and treatment of skin conditions, with “bacterial transplants” and probiotic treatments emerging as alternatives to traditional antibiotics that can disrupt these delicate microbial balances.

Malassezia: The Fungi Among Us

Beyond bacteria and arthropods, your skin hosts various fungal species, with Malassezia being particularly prominent. These yeasts thrive in oil-rich areas like the scalp, face, and upper body, feeding on the sebum produced by sebaceous glands. While present on virtually everyone’s skin, Malassezia exists in a delicate balance that, when disrupted, can contribute to conditions like dandruff, seborrheic dermatitis, and certain forms of folliculitis. The relationship between humans and Malassezia illustrates the concept of commensalism—these fungi benefit from living on our skin without typically causing harm under normal circumstances. Interestingly, Malassezia species vary globally, with different strains predominating in different geographical regions, suggesting environmental adaptation throughout human history.

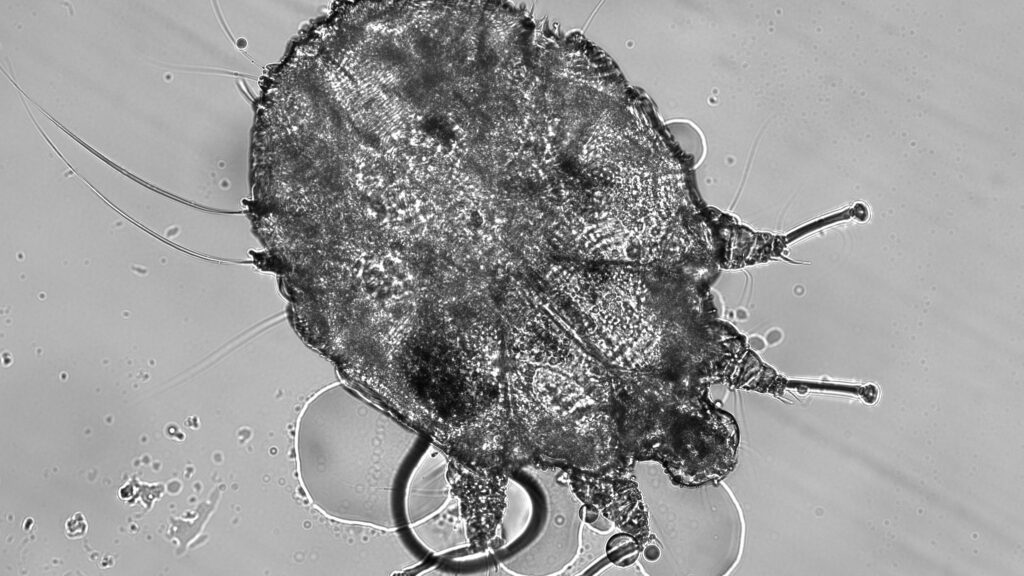

Scabies Mites: The Burrowing Invaders

Unlike demodex mites, which are normal residents of human skin, scabies mites (Sarcoptes scabiei var. hominis) are always considered parasites causing a condition requiring treatment. These microscopic arachnids burrow into the outer layer of skin, creating tunnels where females lay eggs and trigger intense itching, particularly at night. Scabies infestations often concentrate in skin folds like between fingers, around wrists, in armpits, or along the belt line, creating characteristic serpentine burrows visible under magnification. Historically, scabies has affected humans for thousands of years, with descriptions dating back to Aristotle’s time and documented treatments throughout medieval medical texts. While primarily transmitted through prolonged skin-to-skin contact, scabies can sometimes spread through shared bedding or clothing, making it particularly problematic in institutional settings like nursing homes, prisons, and overcrowded refugee camps.

Pubic Lice: Evolutionary Specialists

Pubic lice (Pthirus pubis), colloquially known as “crabs” due to their crab-like appearance, represent a fascinating case of co-evolution and adaptation. These specialized parasites have evolved physical characteristics specifically suited to grip the coarser, more widely-spaced hairs of the pubic region, with powerful claws that distinguish them from head lice. Evolutionary biologists have used genetic studies of these lice to trace human evolutionary history, with evidence suggesting humans acquired pubic lice from gorilla ancestors approximately 3-4 million years ago. Unlike head lice, pubic lice move very slowly, traveling only about 10 cm per day, which influences their primary transmission method through intimate physical contact. Interestingly, some dermatologists have noted declining incidence rates of pubic lice in regions where pubic hair removal has become a common practice, demonstrating how cultural practices can influence parasite populations.

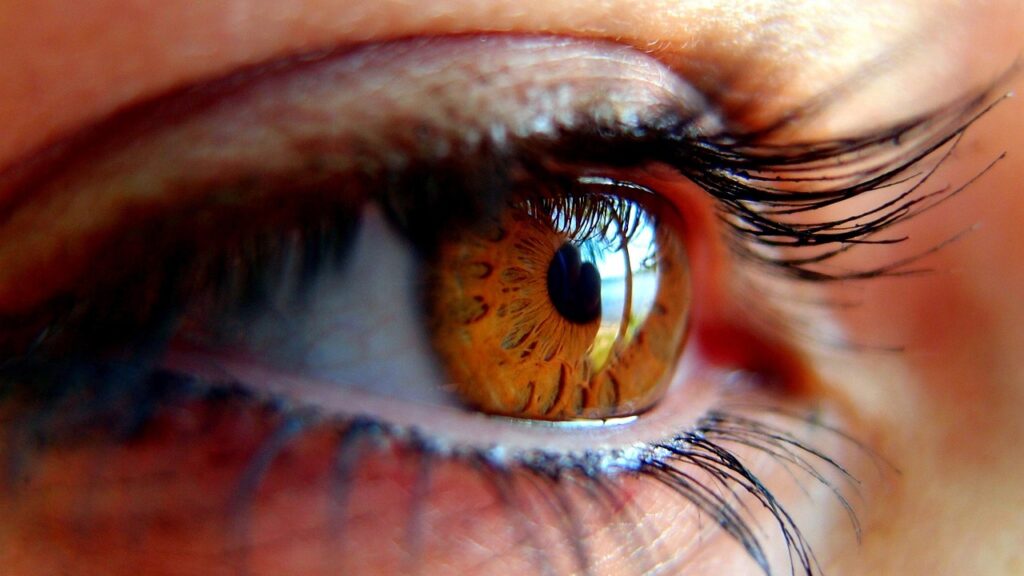

The Eyelash Ecosystem: Specialized Microhabitats

Your eyelashes and surrounding tissue host specialized communities of organisms adapted to this unique microenvironment. Demodex folliculorum particularly favors eyelash follicles, where oil glands provide abundant nutrition for these tiny mites. The eyelid margin also supports distinct bacterial populations, including species of Staphylococcus and Corynebacterium that differ from those elsewhere on the face. This delicate ecosystem plays important roles in ocular health, with disruptions potentially contributing to conditions like blepharitis (eyelid inflammation) and dry eye syndrome. Ophthalmologists have observed that the eyelash microbiome changes with age, with children hosting fewer organisms than adults, and these populations stabilizing in adulthood unless disrupted by disease or medication. Recent studies using advanced genetic sequencing have revealed previously unknown diversity in this region, with dozens of bacterial species coexisting in this tiny habitat.

Body Odor: The Bacterial Signature

The characteristic scent we recognize as body odor isn’t produced directly by our bodies but results from bacterial action on otherwise odorless compounds in sweat. Apocrine glands, concentrated in areas like armpits and the groin, produce protein-rich secretions that skin bacteria—particularly Corynebacterium and certain Staphylococcus species—metabolize into volatile compounds with distinctive odors. This relationship explains why newborn babies lack body odor—they haven’t yet developed the bacterial populations responsible for these transformations. Fascinatingly, genetic factors influence which bacterial species thrive in these areas, with a specific gene variant common in East Asian populations associated with different microbiome compositions and reduced body odor. Anthropologists suggest body odor may have played evolutionary roles in human development, potentially contributing to mate selection through unconscious detection of genetic compatibility or health status.

The Oral Microbiome: Beyond Just Teeth

Your mouth hosts one of the most diverse microbial communities on your body, with over 700 bacterial species identified and each person harboring 200-300 species at any given time. This complex ecosystem extends beyond just teeth and gums to include specialized communities on the tongue, cheeks, palate, and tonsils, each with distinct microbial signatures. The oral microbiome significantly influences both oral and systemic health, with imbalances linked not only to dental caries and periodontal disease but potentially to cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and certain cancers through inflammatory pathways. Bacteria like Streptococcus mutans receive much attention for their role in tooth decay, but many oral bacteria play protective roles, helping to prevent colonization by pathogenic species. Emerging research suggests that certain oral bacteria may even influence nitric oxide production, potentially affecting blood pressure regulation and cardiovascular function.

The Human Microbiome Project: Changing Our Self-Perception

Launched in 2007, the Human Microbiome Project revolutionized our understanding of the microorganisms inhabiting the human body, including those on our skin and external surfaces. This landmark research initiative revealed that microbial cells outnumber human cells by approximately 1.3 to 1, challenging traditional concepts of human identity and individuality. The project mapped microbial communities across multiple body sites, discovering that different regions—even areas just centimeters apart—can host dramatically different microbial populations adapted to local conditions. Perhaps most profoundly, this research has shifted medical paradigms from viewing microorganisms primarily as threats to recognizing them as essential components of human physiology and development. The continued exploration of the human microbiome promises insights into conditions ranging from inflammatory skin diseases to mental health disorders, suggesting future treatments might focus on restoring microbial balance rather than eliminating microorganisms indiscriminately.

Living in Balance: The Future of Human-Microbe Relations

Modern hygiene practices, while crucial for preventing infectious disease, have dramatically altered our relationship with our microbial companions compared to most of human evolutionary history. Emerging evidence suggests that overly aggressive cleansing and antimicrobial products may disrupt beneficial microbial communities, potentially contributing to rising rates of allergic and inflammatory conditions. Forward-thinking researchers are developing “biome-friendly” approaches to personal care that preserve beneficial organisms while controlling potentially harmful ones. Companies now offer personalized microbiome testing and tailored probiotic treatments for skin conditions, signaling a shift toward working with rather than against our microbial partners. Educational initiatives aim to transform public perception from “germophobia” to a more nuanced understanding of microbial ecology, emphasizing that the goal shouldn’t be a sterile existence but rather a balanced relationship with the microscopic life that has evolved alongside us for millennia.

Conclusion

The microscopic inhabitants of our bodies represent not invaders but partners in an ancient evolutionary relationship. From the demodex mites nestled in our follicles to the diverse bacterial communities across our skin, these organisms have shaped human biology and continue to influence our health in profound ways. Understanding this complex ecosystem challenges us to reconsider what it means to be human—we are not isolated individuals but walking ecosystems, our bodies serving as landscapes for countless microscopic lives. As research advances, our relationship with these tiny companions will likely evolve from fear and disgust toward appreciation and stewardship, recognizing that our well-being is inextricably linked with the well-being of the smallest members of our biological community. Far from being a cause for alarm, the bugs on our bodies tell a remarkable story of coexistence, adaptation, and the intricate interconnectedness of all life.