In the intricate web of nature’s relationships, predator-prey dynamics take countless forms. While we often think of parasites as the villains of the natural world, there exists a fascinating ecological niche where parasites themselves become victims. This phenomenon, known as hyperparasitism, involves parasites that specifically target other parasites. This multi-layered parasitic relationship creates a biological Russian nesting doll effect that highlights the complexity of evolution and adaptation. From microscopic wasps that lay eggs inside aphids already hosting other parasites, to fungi that colonize insect-attacking nematodes, these remarkable relationships demonstrate nature’s endless capacity for specialization and the eternal evolutionary arms race between organisms.

The Concept of Hyperparasitism Explained

Hyperparasitism represents one of nature’s most intricate ecological relationships, occurring when one parasite species becomes the host for another parasite. In this fascinating biological hierarchy, the secondary parasite (hyperparasite) exploits the primary parasite, which is already exploiting its own host. This creates a multi-tiered system of parasitism that can sometimes extend to tertiary or even quaternary levels in extremely complex cases. For insects, hyperparasitism often manifests when parasitoid wasps lay eggs in other parasitoid larvae or pupae that are already developing inside a host insect. The hyperparasite essentially “hijacks” the resources that the primary parasite has already stolen from the original host, demonstrating an evolutionary strategy that capitalizes on the work already done by another organism.

The Evolutionary Arms Race

The development of hyperparasitism represents a fascinating chapter in the ongoing evolutionary arms race between parasites and their hosts. As primary parasites evolve mechanisms to successfully exploit their hosts, they simultaneously face selection pressure to develop defenses against potential hyperparasites. This creates a cascade of adaptations and counter-adaptations across multiple trophic levels, driving genetic diversity and specialized adaptations throughout the ecosystem. Primary parasites may develop chemical defenses, behavioral strategies, or immunological responses to prevent hyperparasite attacks, while hyperparasites evolve increasingly sophisticated methods to overcome these barriers. This multi-level selective pressure creates some of the most specialized organisms on Earth, with hyperparasites often possessing remarkable abilities to detect hosts, neutralize defenses, and precisely time their attacks to maximize reproductive success.

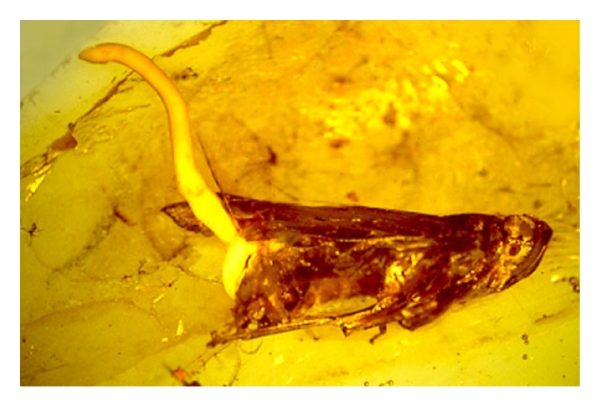

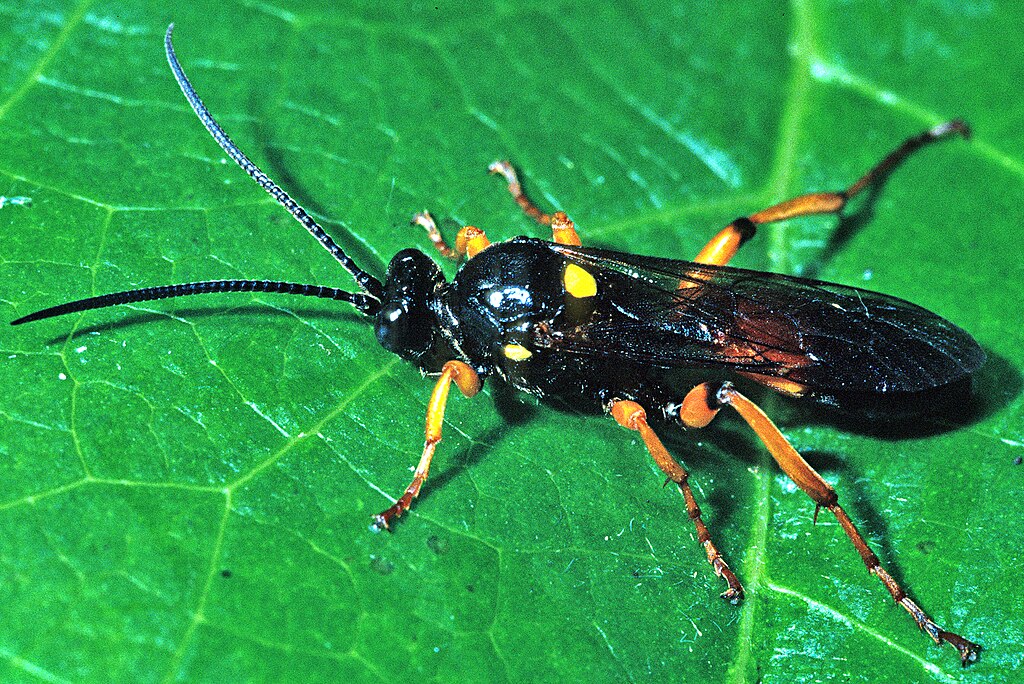

Parasitoid Wasps: Masters of Hyperparasitism

Among the insect world’s most accomplished hyperparasites are certain species of parasitoid wasps, particularly within families like Ichneumonidae and Braconidae. These remarkable insects have evolved highly specialized strategies for detecting and exploiting other parasitoids already developing inside host insects. Using sensitive chemoreceptors, female hyperparasitic wasps can identify hosts containing primary parasitoids through subtle chemical signatures that would be imperceptible to most other organisms. Some species, like those in the genus Lysibia, specifically target the cocoons of primary parasitoid wasps, injecting their eggs directly into the developing pupae inside. The hyperparasitoid larvae then consume the primary parasitoid from within, timing their development to perfectly coincide with the maturation of their victim and thus maximizing nutrient availability.

Mites that Parasitize Parasitic Insects

Parasitic mites represent another fascinating group of arthropods that have evolved to exploit parasitic insects. Species such as Hemisarcoptes cooremani specialize in attaching to and feeding upon scale insects that are themselves plant parasites, creating a hyperparasitic relationship. Some mesostigmatid mites have developed even more specialized strategies, targeting parasitoid wasps by attaching to female wasps and hitching rides to new host insects. Once arrived, these mites detach and begin feeding on the eggs or larvae that the wasp has just deposited, effectively parasitizing the parasite. The relationship between certain phoretic mites and parasitoid wasps demonstrates remarkable co-evolutionary adaptations, with mites developing specialized attachment structures and sensory organs to coordinate their life cycles with their wasp carriers.

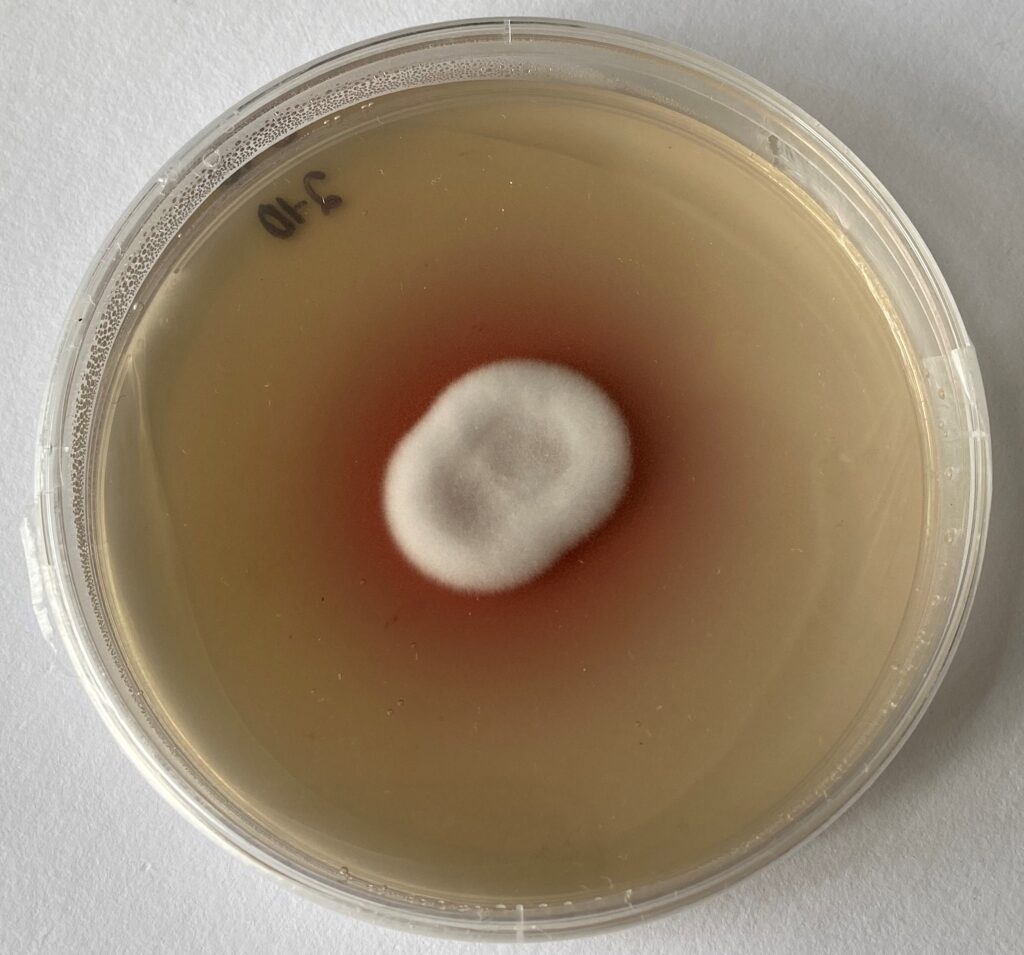

Fungal Hyperparasites: Silent Infiltrators

The fungal kingdom contains some of the most effective and specialized hyperparasites that target insect parasites. Genera such as Lecanicillium and Ampelomyces have evolved to specifically infect and consume other parasitic fungi that attack insects, creating a tripartite relationship where fungi parasitize fungi that parasitize insects. These hyperparasitic fungi typically produce specialized penetration structures that can breach the cell walls of their fungal hosts, allowing them to extract nutrients directly from the primary parasite. Some hyperparasitic fungi like Trichoderma species can detect volatile compounds produced by plant-pathogenic fungi and grow directionally toward them, demonstrating sophisticated chemosensory abilities. The ecological significance of these fungal hyperparasites extends beyond natural systems, as researchers have explored their potential as biological control agents against harmful primary parasites in agricultural settings.

Viral Hyperparasitism in the Insect World

Viruses represent perhaps the ultimate parasites, and in the insect world, they sometimes function as hyperparasites by infecting organisms that are themselves parasites. One striking example involves certain bacteriophages (viruses that infect bacteria) that target bacterial symbionts of parasitic insects like aphids or whiteflies. When these viruses disrupt the function of beneficial bacteria that the insect parasites depend upon, they effectively act as hyperparasites by indirectly harming the insect parasite through its microbial partner. Some parasitic wasps have even evolved to use viruses as weapons, injecting polydnaviruses along with their eggs to suppress the host insect’s immune system and create a more favorable environment for their developing young. These viral-wasp relationships represent one of the most intricate examples of biological weaponry in nature, with the viruses functioning as living immunosuppressants that benefit their wasp carriers.

Nematodes: Worms that Target Parasitic Insects

Nematode worms have evolved multiple strategies for hyperparasitism, with some species specifically targeting insects that are themselves parasites. Certain mermithid nematodes, for instance, parasitize mosquito larvae that would otherwise grow into blood-feeding parasites of vertebrates, creating a hyperparasitic relationship that humans sometimes exploit for biological control. The nematode Strelkovimermis spiculatus specializes in parasitizing the aquatic larvae of several mosquito species, developing inside the mosquito and eventually killing it before it can complete metamorphosis. Some entomopathogenic nematodes like Heterorhabditis species carry symbiotic bacteria that help them overcome the immune defenses of their insect hosts, which may themselves be parasites of plants or other animals. These complex relationships highlight how hyperparasitism often involves not just two species but entire communities of organisms with interconnected evolutionary histories.

Chemical Warfare in Hyperparasitic Relationships

The battles between parasites and their hyperparasites often play out at the biochemical level, with both sides deploying sophisticated chemical weaponry. Primary parasitic insects frequently produce antimicrobial peptides, enzymes, and other defensive compounds to ward off potential hyperparasites that might target them during vulnerable developmental stages. Hyperparasites counter these defenses with specialized detoxification enzymes, immune suppressors, and molecular mimicry strategies that allow them to evade detection by their parasitic hosts. The venom of many hyperparasitic wasps contains cocktails of bioactive compounds including neurotoxins, cytolytic peptides, and enzyme inhibitors specifically evolved to overcome the particular physiological defenses of their parasitoid targets. This molecular arms race drives the evolution of increasingly complex biochemical pathways and specialized compounds, making these organisms valuable sources for bioprospecting in pharmaceutical research.

Ecological Impact of Insect Hyperparasitism

Hyperparasitism plays a crucial role in regulating ecological communities by adding another layer of population control to parasitic insects. By preventing any single parasite species from becoming too abundant, hyperparasites help maintain biodiversity and ecological balance in natural systems. In agricultural contexts, hyperparasites can complicate biological control efforts, sometimes undermining attempts to control pest insects using primary parasitoids by attacking and killing the very biocontrol agents that farmers or researchers have introduced. Some ecological models suggest that hyperparasitism contributes to the cyclical population dynamics observed in many insect communities, with hyperparasite populations lagging behind those of primary parasites, which themselves lag behind host populations. The presence of hyperparasites in an ecosystem often indicates high biodiversity and complex community structure, as these specialized organisms typically require stable populations of both hosts and primary parasites to persist.

Behavioral Adaptations of Hyperparasites

Hyperparasitic insects have evolved remarkable behavioral adaptations to locate and successfully exploit their parasitic hosts. Many hyperparasitic wasps display sophisticated host-searching behaviors, using a combination of visual cues, chemical sensing, and sometimes even vibrational information to identify potential hosts. Species like Lysibia nana can detect the subtle changes in plant volatiles that occur when a plant is being attacked by a herbivore that contains a developing parasitoid, allowing them to locate potential hosts with remarkable precision. Some hyperparasitoids have evolved to time their attacks to specific developmental stages of the primary parasite, requiring precise synchronization of their life cycles with those of both the primary parasite and the original host. Hyperparasites often exhibit complex decision-making processes when encountering potential hosts, assessing factors like host quality, competition from other hyperparasites, and risk of predation before committing to parasitism.

The Challenge of Studying Hyperparasites

Researching hyperparasitic relationships presents unique challenges due to the microscopic size and complex life histories of many hyperparasites. Scientists must often employ sophisticated rearing techniques, molecular tools, and advanced imaging to properly document and understand these multi-level parasitic interactions. The temporal nature of hyperparasitism further complicates research, as investigators must track organisms through multiple generations and life stages to fully characterize the relationship. Field studies of hyperparasitism are particularly challenging, as researchers must account for environmental variables that might influence hyperparasite behavior while also capturing the ephemeral nature of many hyperparasitic interactions. Despite these difficulties, modern genomic tools have revolutionized the study of hyperparasitism, allowing scientists to identify genetic signatures of co-evolution and adapt-counteredapt relationships that would be impossible to detect through observation alone.

Hyperparasites in Biological Control

The presence of hyperparasites creates both opportunities and challenges for biological control programs aimed at managing agricultural pests. While hyperparasites can undermine biological control by attacking beneficial primary parasitoids, they can sometimes be harnessed to target harmful parasites that affect beneficial insects like pollinators. Agricultural scientists must consider the entire community of potential hyperparasites when designing integrated pest management programs, sometimes selecting primary parasitoids that are less susceptible to hyperparasitism for field releases. Some innovative approaches have explored using hyperparasites themselves as biocontrol agents, particularly against invasive parasites that lack natural enemies in introduced regions. Understanding the host specificity and environmental requirements of hyperparasites has become increasingly important in risk assessment for biological control, as researchers work to predict and prevent unintended ecological consequences of deliberate organism introductions.

Future Research Directions in Insect Hyperparasitism

The frontier of hyperparasitism research offers numerous exciting directions for future scientific inquiry. Emerging genomic and transcriptomic approaches promise to reveal the molecular mechanisms underlying the intricate host-finding, immune evasion, and physiological manipulation strategies employed by hyperparasites. Climate change presents an urgent research need, as shifting temperatures and precipitation patterns may disrupt the delicate synchronization between hyperparasites, primary parasites, and their hosts, potentially destabilizing ecological communities. Microbiome research represents another promising avenue, as scientists increasingly recognize that many hyperparasitic relationships involve not just the visible organisms but also their associated microbial communities, including bacteria and viruses that may themselves function as hyperparasites. Developing new mathematical models to predict the population dynamics of multi-level parasitic systems will be crucial for both basic ecological understanding and applied contexts like agricultural pest management in an increasingly complex global environment.

Conclusion

The intricate world of hyperparasitism reminds us that nature’s relationships rarely follow simple predator-prey dynamics. Instead, they form complex networks where the roles of victim and exploiter can shift depending on perspective. These parasites of parasites have evolved some of the most specialized adaptations on Earth, from molecular mimicry to sophisticated host-finding behaviors. As scientists continue to unravel these relationships, they not only enhance our understanding of evolutionary processes but also discover potential applications in fields ranging from biological control to pharmacology. In studying these microscopic dramas, we glimpse the elegant complexity that emerges from millions of years of co-evolutionary pressure—a testament to nature’s endless capacity for innovation within constraint.