In the intricate world of social insects, ants have developed a remarkable system for maintaining colony health and hygiene. Among their most fascinating behaviors is necrophoresis – the organized removal and disposal of dead nestmates. This undertaking behavior serves as a critical disease prevention mechanism within ant colonies, where thousands of individuals live in close proximity. The ant undertakers, or “necrophores,” are specialized workers that detect, transport, and dispose of the deceased, creating a natural sanitation system that has evolved over millions of years. This meticulous corpse management not only reveals the complex social structure of ant colonies but also provides insights into disease management strategies in densely populated communities.

The Discovery of Necrophoresis in Ant Colonies

The systematic removal of dead nestmates in ant colonies was first documented by early myrmecologists (ant scientists) in the late 19th century, though indigenous knowledge of this behavior likely predates scientific recording. Edward O. Wilson, the renowned entomologist, conducted groundbreaking research on this phenomenon in the 1950s and 1960s, establishing it as a fundamental aspect of social insect behavior. Wilson’s work revealed that this wasn’t merely random housekeeping but a specialized task performed by dedicated workers within the colony’s division of labor. The term “necrophoresis” was formally adopted to describe this behavior, derived from Greek words meaning “corpse carrier,” accurately capturing the essence of this undertaking role in ant societies.

Chemical Triggers of Corpse Recognition

The primary mechanism through which ant undertakers identify their dead is remarkably chemical in nature. When an ant dies, its body begins to produce oleic acid and other fatty acids as decomposition starts, creating what scientists call a “death signature.” These chemical compounds serve as unmistakable signals to necrophore ants that a colony member has died and requires removal. Interestingly, researchers have demonstrated that coating a live ant with oleic acid can trigger necrophoric behavior, with undertaker ants attempting to transport the still-living nestmate to the colony’s waste pile. This chemical recognition system is so efficient that undertakers can typically identify a dead nestmate within an hour of death, allowing for prompt removal before disease can spread through the colony.

The Role of Age in Undertaking Behavior

Ant colonies exhibit a fascinating age-based division of labor, with necrophoric duties typically assigned to middle-aged workers. Young ants generally focus on nursing larvae and caring for the queen, while the oldest workers become foragers who venture outside the nest. The undertaker role represents a transitional phase in an ant’s life cycle, occurring after internal nest duties but before the riskier foraging activities. This age-based specialization makes biological sense, as middle-aged ants have completed their crucial reproductive support tasks but aren’t yet committed to the dangerous world outside the nest. Some studies suggest that these middle-aged undertakers have more developed olfactory systems, making them better equipped to detect the subtle chemical signatures of death and decay.

Specialized Disposal Sites: The Ant Graveyards

Ant colonies maintain dedicated waste management areas that serve as disposal sites for their dead, often called “ant graveyards” or “refuse piles.” These sites are strategically located away from nesting chambers, food storage areas, and nurseries to minimize contamination risks. In some species, these disposal sites are found in specific chambers within the nest structure, while other species transport their dead to external locations that can be several meters from the nest entrance. Leaf-cutter ants are particularly methodical, maintaining underground chambers specifically for waste and dead ants, complete with workers assigned to manage these disposal sites. These natural cemeteries create a sanitary buffer zone that helps protect the colony from potential pathogens that might develop as bodies decompose.

Corpse Management Techniques Across Ant Species

Different ant species have evolved varying techniques for handling their dead, adapting to their specific environments and colony structures. Fire ants (Solenopsis invicta) typically carry their dead to designated refuse piles outside the nest, while Argentine ants (Linepithema humile) may form “ant cemeteries” in protected locations away from high-traffic areas. Pharaoh ants (Monomorium pharaonis) exhibit particularly fascinating behavior, where undertakers may dismember larger dead ants to facilitate easier transport to disposal sites. Honeypot ants (Myrmecocystus) living in arid environments often carry their dead far from the nest entrance and leave them exposed to the desiccating effects of the sun, essentially mummifying them and reducing disease risk. These diverse management techniques highlight how evolution has shaped specialized solutions to the universal problem of corpse disposal in social insects.

The Connection Between Necrophoresis and Disease Prevention

Necrophoresis represents one of the most effective disease management strategies in the insect world, playing a crucial role in limiting pathogen spread within dense ant colonies. Dead insects quickly become breeding grounds for bacteria and fungi that could devastate a colony if left unchecked. Research has demonstrated that colonies with efficient necrophoric behavior show significantly reduced rates of epidemic outbreaks compared to colonies where corpse removal is artificially prevented. This sanitation system is particularly important because ants live in environments with high humidity and temperature conditions that would otherwise accelerate decomposition and pathogen growth. The rapid identification and removal of dead nestmates effectively creates a form of “social immunity” that complements each individual ant’s immune system, forming a multi-layered defense against disease.

Collective Decision-Making in Corpse Management

The process of identifying and removing dead ants involves sophisticated collective decision-making that doesn’t rely on centralized control. When an undertaker ant encounters a corpse, it doesn’t act alone but often recruits additional workers through chemical trails and tactile communication. Researchers have observed that the number of necrophores recruited correlates with the size of the corpse and the perceived threat level, with more workers responding to corpses showing signs of infectious disease. This recruitment system ensures efficient resource allocation, preventing too many workers from being diverted from other essential colony tasks. The collective nature of the response also creates redundancy in the system, ensuring that corpse removal continues even if some undertakers become compromised or are unable to complete their task.

Necrophoresis in Other Social Insects

While ants have the most well-documented undertaking behaviors, similar necrophoric practices appear across various social insect species. Honeybees (Apis mellifera) employ specialized undertaker bees that remove dead nestmates from the hive, typically dragging them out and dropping them at a distance from the colony. Termites demonstrate particularly sophisticated corpse management, sometimes using antimicrobial substances in their saliva to treat corpses before burial or incorporating the dead into nest structures after treatment. Some stingless bee species even engage in corpse “embalming” by coating dead nestmates with plant resins that have antimicrobial properties before removal. These parallel evolutionary developments across different insect lineages highlight how important corpse management is for any species living in dense, social colonies.

Environmental Factors Affecting Undertaking Behavior

The efficiency of necrophoric behavior can be significantly influenced by environmental conditions, with temperature playing a particularly important role. Warmer temperatures accelerate decomposition and the release of oleic acid, making corpse detection faster but also increasing the urgency of removal. During colder periods, chemical detection may be delayed, potentially increasing disease risk in the colony. Humidity levels also affect the undertaking process, with higher humidity accelerating decomposition but potentially making corpse transport more difficult in some species. Researchers have observed that some ant colonies alter their undertaking strategies seasonally, with more aggressive removal during warm, humid periods when disease risks are highest, demonstrating the adaptive nature of this behavior in response to environmental conditions.

Learning and Memory in Necrophore Ants

Recent research suggests that necrophore ants may develop specialized memory and learning capabilities related to their undertaking duties. Studies indicate that experienced undertakers become more efficient at identifying corpses and selecting optimal transport routes to disposal sites compared to novice workers. This learning process appears to involve both individual experience and social learning, where younger ants may observe and learn from more experienced necrophores. Some experiments have shown that colonies exposed to repeated corpse removal scenarios develop more efficient undertaking systems over time, suggesting a form of collective learning at the colony level. These cognitive adaptations highlight the sophisticated nature of ant societies and challenge simplistic views of insect behavior as purely instinctive.

The Evolutionary Origins of Necrophoresis

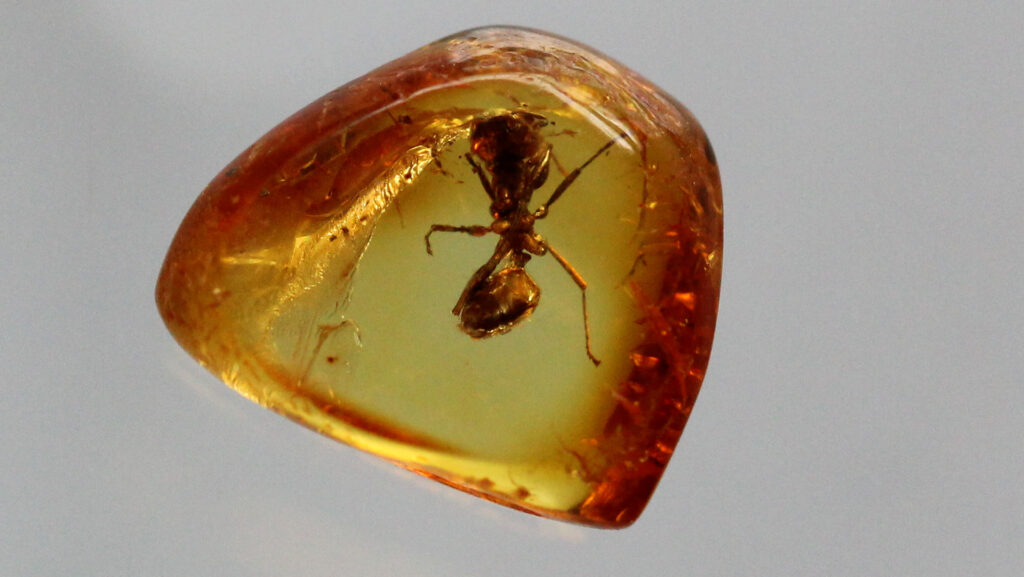

Evolutionary biologists believe that necrophoresis evolved as a critical adaptation to the disease challenges inherent in social living. The archaeological record suggests that this behavior has existed for at least 50 million years, with amber fossils showing ancient ants engaged in corpse transport. The behavior likely developed from more general waste removal instincts that were already present in the solitary ancestors of modern ants. As colony sizes increased through evolutionary time, the selective pressure for effective sanitation would have intensified, leading to the specialized necrophoric behaviors we observe today. Comparative studies across ant species with different colony structures support this theory, with larger, more densely populated colonies typically showing more sophisticated undertaking behaviors than species with smaller colonies.

Applications and Inspirations for Human Disease Management

The efficient disease management systems of ant colonies have inspired researchers in fields ranging from public health to robotics. Epidemiologists study ant necrophoresis to better understand how simple rules followed by individuals can create effective collective disease management in human populations. Computer scientists have developed algorithms based on ant undertaking behavior to create more efficient waste management systems and optimize sanitation resource allocation in urban planning. Robotics engineers have designed swarm robots that mimic necrophoric behavior for applications in disaster response, where robot “undertakers” could remove dangerous materials from contaminated areas. These biomimetic applications demonstrate how ancient solutions evolved in the natural world can inform cutting-edge approaches to modern human challenges in disease control and waste management.

Conclusion

The phenomenon of necrophoresis in ant colonies represents one of nature’s most elegant solutions to disease management in social communities. These tiny undertakers, carrying out their solemn duties with chemical precision, help ensure the survival of their colonies through a behavior that evolved millions of years before human understanding of germ theory. The study of ant necrophores continues to yield insights not only about social insect behavior but also about fundamental principles of disease management in any densely populated community. As we face our own challenges with infectious disease control in human populations, these industrious undertakers remind us that sometimes the most effective solutions come from observing the time-tested strategies that have evolved in the natural world.