In the natural world, color is more than decoration—it’s communication. Among the most striking examples are insects that display vivid, high-contrast patterns and neon-like hues that seem almost artificial in their brilliance. These eye-catching colors aren’t random fashion choices but sophisticated visual signals developed over millions of years of evolution. From the fiery orange of monarch butterflies to the metallic gleam of jewel beetles, these vibrant displays serve crucial purposes in survival, reproduction, and species interaction. This fascinating intersection of biology, ecology, and visual communication reveals how insects use their bodies as canvases for messages that can mean the difference between life and death in the wild.

The Evolutionary Purpose of High-Contrast Coloration

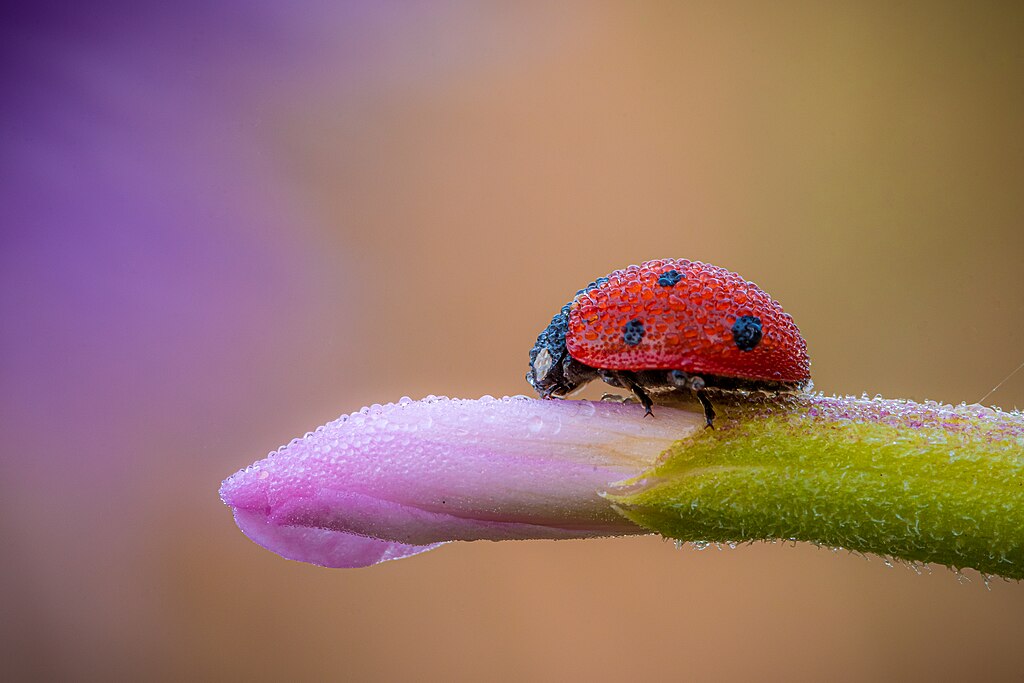

High-contrast coloration in insects represents one of evolution’s most sophisticated visual strategies, fine-tuned over millions of years. These striking patterns and colors didn’t develop for aesthetic reasons but emerged as powerful tools for survival and reproduction. Natural selection has favored insects whose colors effectively communicate specific messages to predators, potential mates, or competitors. The development of these color patterns often represents an evolutionary arms race between species, where visibility must be balanced against vulnerability. Some of the most dramatic examples, such as the stark black and yellow of wasps or the brilliant red of certain beetles, have proven so effective that they’ve remained relatively unchanged for thousands of generations, demonstrating the remarkable stability of successful evolutionary adaptations.

Aposematism: Nature’s Warning Labels

Aposematism represents one of the most common functions of bright coloration in the insect world, serving as nature’s equivalent of warning labels. When insects display combinations like yellow and black, orange and black, or bright red, they’re typically advertising their unpalatability, toxicity, or ability to inflict pain. This warning system works because predators learn to associate these distinctive patterns with negative experiences after attempting to eat such insects. The monarch butterfly’s orange and black pattern, for instance, signals its body contains toxic cardiac glycosides acquired from milkweed plants during its larval stage. The effectiveness of aposematic coloration depends on predator learning and memory, creating an evolutionary incentive for dangerous insects to evolve similar warning patterns that reinforce this visual language of danger throughout the ecosystem.

Mimicry: The Art of Deceptive Coloration

Mimicry represents one of nature’s most sophisticated visual deception strategies, where harmless insects evolve to resemble dangerous or toxic species. Batesian mimicry occurs when a non-toxic species, like the viceroy butterfly, evolves to resemble a toxic model, such as the monarch butterfly, thereby gaining protection without the physiological cost of producing toxins. Müllerian mimicry, by contrast, involves multiple dangerous species evolving similar warning patterns, which reinforces predator learning and provides mutual protection. Some insects even engage in aggressive mimicry, where predatory species mimic harmless or attractive ones to lure in prey. The remarkable precision of these mimicry systems often extends beyond color to include behavior, body shape, and movement patterns, creating multi-layered deceptions that demonstrate the extraordinary power of selection pressure on visual signaling.

The Science of Iridescence in Insects

Iridescence in insects represents one of nature’s most complex optical phenomena, creating color not through pigments but through microscopic physical structures. Unlike standard coloration, iridescent surfaces change color depending on the viewing angle, producing the metallic, shifting hues seen in morpho butterflies, jewel beetles, and certain flies. This structural color results from nanoscale surface features that cause light wave interference, diffraction, and scattering. Electron microscope studies reveal these surfaces contain precisely arranged ridges, scales, or layered structures that selectively reflect specific wavelengths of light. What makes insect iridescence particularly remarkable is its evolutionary development without conscious design—natural selection has shaped these intricate nanostructures to serve specific communication purposes, whether attracting mates, confusing predators, or regulating body temperature in various environments.

UV Patterns: The Hidden Signals Humans Can’t See

Many insects possess a secret visual language invisible to the human eye but brilliantly clear to other insects and certain predators—ultraviolet (UV) reflective patterns. These hidden signals exist because many insects can perceive UV light, a capability humans lack. Butterfly wings that appear plain white to us may display complex ultraviolet patterns that serve as species recognition markers or courtship signals. Scientists using specialized UV photography have revealed these hidden patterns, showing how flowers use UV “runways” to guide pollinators to nectar, and how some predatory insects use UV markings to attract prey. This invisible dimension of insect coloration demonstrates how our understanding of animal communication remains limited by our own sensory capabilities. Research into UV patterns continues to reveal increasingly sophisticated signaling systems operating beyond human perception, highlighting how much of nature’s visual communication occurs on wavelengths we cannot naturally detect.

Sexual Selection and Flamboyant Displays

Many of the most spectacular insect color displays evolved primarily through sexual selection, where vibrant colors and patterns serve as indicators of genetic fitness to potential mates. Male peacock spiders, for instance, possess brilliantly colored abdominal flaps they raise and wave in elaborate courtship dances to impress females. In many butterfly species, wing patterns serve as species-specific identification markers that help individuals recognize suitable mates while avoiding hybridization with similar species. The intensity of these displays often correlates with male health and genetic quality, as producing and maintaining bright colors requires considerable physiological resources. Sexual selection has driven some of the most rapid and extreme color evolution in insects, particularly when female preference favors increasingly elaborate displays over time. This process explains why closely related species sometimes differ dramatically in coloration, as sexual selection can drive divergent evolution much faster than natural selection for survival traits.

Thermoregulation Through Color

Beyond communication, many insects use color as a sophisticated thermoregulation tool, employing dark pigments to absorb heat or reflective surfaces to deflect it. Desert-dwelling beetles often have black elytra (wing covers) that rapidly absorb morning sunlight, warming their bodies to optimal operating temperatures before potential competitors become active. Conversely, some insects that risk overheating in direct sunlight possess highly reflective white or metallic surfaces that redirect light energy away from their bodies. Certain butterflies can adjust their wing position relative to the sun to either increase heat absorption on cool mornings or minimize it during midday heat. Some species even display seasonal color changes, with darker forms emerging during cooler months and lighter forms appearing during warmer seasons. This thermoregulatory function demonstrates how insect coloration often serves multiple adaptive purposes simultaneously, balancing communication needs with physiological requirements.

Predator Confusion: Disruptive Coloration and Flash Displays

Some of the most visually striking insect color patterns evolved specifically to confuse predator visual systems and disrupt attack sequences. Disruptive coloration breaks up an insect’s outline with contrasting patches of color that make its true shape difficult to recognize against complex backgrounds. Many moths employ this strategy with patterns that visually fragment their silhouette. Flash displays represent another defense tactic, where insects suddenly reveal hidden bright colors when disturbed. The underwing moths exemplify this strategy, with cryptic outer wings that conceal vivid red, orange, or yellow hindwings only exposed when the moth is flushed from hiding. This sudden color change momentarily startles predators and may create tracking confusion as the bright color disappears when the insect lands and folds its wings. Some grasshoppers and katydids combine flash displays with defensive sounds, creating multi-sensory deterrents that exploit predator startle responses.

Fireflies and Bioluminescence: Living Light Displays

Perhaps the most magical form of insect visual signaling comes from species capable of producing their own light through bioluminescence. Fireflies (lightning bugs) represent the most familiar example, using specialized light-producing organs containing the enzyme luciferase, which catalyzes a chemical reaction producing light with virtually no heat. Each firefly species employs distinctive flash patterns—specific sequences of light pulses with precise timing—that function as a living Morse code for species recognition and mating signals. Males typically flash while flying, while females respond from perches with precisely timed answering flashes. Some predatory firefly females mimic the response patterns of other species to lure males in as prey. Beyond fireflies, bioluminescence appears in various insects including certain click beetles and railroad worms, each evolving this remarkable capability independently. These living light displays remind us that insects have evolved visual communication systems that go beyond passive coloration to include active light generation.

Crypsis and Counter-Shading: The Anti-Contrast Strategy

While this article focuses primarily on high-contrast, visible colors, it’s worth noting that many insects employ the opposite strategy—crypsis, or camouflage—sometimes alongside bright warning colors. Counter-shading, where an insect’s upper surface is darker than its undersides, counteracts natural shadows and helps the animal blend seamlessly into its environment. Some insects possess both cryptic and aposematic coloration on different body parts, displaying dull camouflage at rest but revealing warning colors when disturbed. The peppered moth famously demonstrates how quickly cryptic coloration can evolve in response to environmental changes, shifting from primarily light-colored populations to predominantly dark ones during the Industrial Revolution as soot darkened tree trunks. Even insects with primarily warning coloration may incorporate elements of disruptive patterning that break up their outline or make their distance and movement harder for predators to judge accurately. This integration of multiple color strategies highlights the sophisticated visual adaptations insects have evolved to navigate complex environments.

Extraordinary Examples: The Most Striking Insect Color Displays

Among the insect world’s most spectacular color displays, the blue morpho butterfly stands out with wings that flash an electric blue visible from remarkable distances, created not by pigments but by microscopic scales that reflect light at specific wavelengths. The orchid mantis represents another extreme, with its body parts evolved to mimic flower petals in both shape and color so convincingly that it attracts pollinating insects as prey. The jewel beetle family displays metallic colors so intense they’ve been used as decorative elements in human art for centuries, their exoskeletons containing precisely arranged reflective layers that create their distinctive shine. Perhaps most remarkable are the Malaysian lantern bugs, with their elongated heads that glow with an almost ethereal blue-green phosphorescence, combined with wings patterned like eyes to create one of nature’s most alien-looking insects. These extreme examples demonstrate the extraordinary diversity of color production mechanisms that have evolved in insects, pushing the boundaries of what’s biologically possible in visual signaling.

Conservation Implications of Insect Coloration

The vibrant colors that make many insects so fascinating also create unique conservation challenges and opportunities. Brightly colored species often attract disproportionate human attention, sometimes becoming flagship species for habitat protection efforts despite not always being the most ecologically important or endangered insects in a given ecosystem. Climate change poses particular threats to insects with color-based mating systems, as shifting seasonal patterns can disrupt the timing of color development or alter the light conditions under which courtship displays evolved to be most effective. Pollution can directly impact insect coloration by interfering with pigment production or damaging the nanoscale structures that create structural colors. Conservation efforts increasingly consider these complex interactions between insect visual signaling and environmental changes, recognizing that preserving the conditions under which these sophisticated color systems evolved is crucial for maintaining biodiversity. By understanding the ecological significance of insect coloration, conservationists can better monitor ecosystem health and detect subtle environmental shifts before they cause population collapses.

Conclusion

In the world of insects, color tells stories of survival, reproduction, deception, and warning. These magnificent displays represent millions of years of evolutionary refinement, creating visual signals precisely tuned to communicate with predators, potential mates, and competitors. From the warning colors that announce toxicity to the flashy displays that attract mates, from the hidden UV patterns invisible to human eyes to the living light of fireflies, insect coloration demonstrates nature’s remarkable capacity for developing sophisticated communication systems. As we face global biodiversity challenges, understanding these visual languages becomes increasingly important for conservation. The next time you spot a brilliantly colored insect, remember you’re witnessing not just a beautiful creature, but an organism engaged in visual communication refined over countless generations—a living canvas carrying messages essential to its survival in the complex drama of life.