In a world where global travel and commerce move at lightning speed, unwelcome hitchhikers often tag along—invasive insects that not only disrupt ecosystems but also pose significant threats to human health. These tiny invaders cross borders undetected, establishing themselves in new territories where natural predators are absent and conditions favor explosive population growth. From disease-carrying mosquitoes to venomous fire ants, invasive insects have become more than just nuisances; they represent genuine public health concerns with economic, social, and medical ramifications. This article explores the most significant invasive insect species affecting human health globally, examining how they spread, the health risks they pose, and what can be done to mitigate their impact in an increasingly interconnected world.

The Global Impact of Invasive Insects

Invasive insects cost the global economy an estimated $70 billion annually, with health-related costs comprising a significant portion of this figure. These non-native species thrive in new environments due to lack of natural predators, changing climate conditions, and human activities that facilitate their spread. The World Health Organization identifies insect-borne diseases as responsible for over 700,000 deaths annually, with invasive species expanding the reach of many of these illnesses into previously unaffected regions. Beyond direct health impacts, these invaders affect agriculture, forestry, and tourism, creating cascading effects on food security and economic stability that indirectly impact human wellbeing. The CDC now monitors over 20 invasive insect species with known public health implications in the United States alone, highlighting the growing significance of this biological threat.

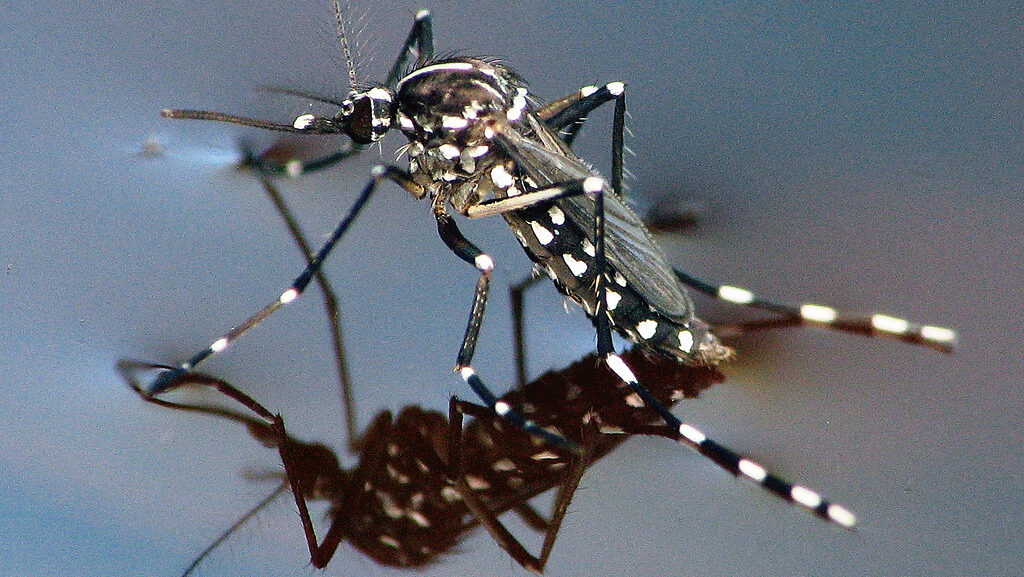

Asian Tiger Mosquito: A Global Disease Vector

The Asian tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus), recognizable by its distinctive black and white striped legs and body, has emerged as one of the world’s most invasive mosquito species since spreading from Southeast Asia in the 1980s. This aggressive daytime biter can transmit more than 20 different viruses to humans, including dengue, chikungunya, Zika, and various forms of encephalitis. Unlike many mosquitoes that breed in natural water bodies, the Asian tiger mosquito thrives in small water containers in urban environments—from discarded tires to flower pot saucers—making it particularly adaptable to human settlements across diverse climates. Its expansion across Europe, the Americas, and Africa has been linked to international trade in used tires and lucky bamboo plants, demonstrating how global commerce unwittingly facilitates the spread of health threats.

Aedes aegypti: The Yellow Fever Mosquito

Originally native to Africa, Aedes aegypti has become one of history’s most impactful invasive species, responsible for transmitting yellow fever, dengue, chikungunya, and Zika viruses to hundreds of millions of people annually. This highly domesticated mosquito species has evolved to live almost exclusively around human habitations, breeding in artificial containers and preferentially feeding on human blood. Its spread has been particularly concerning in the Americas, where it was once eradicated from many countries but has now reestablished itself throughout the region, causing recurring epidemics. What makes this mosquito particularly effective as a disease vector is its nervous feeding behavior—often biting multiple people during a single blood meal, efficiently spreading pathogens through communities. Climate change is now expanding suitable habitat for this tropical mosquito into more temperate regions, potentially exposing millions more people to the diseases it carries.

Fire Ants: Painful Invaders with Deadly Potential

The red imported fire ant (Solenopsis invicta), native to South America, has established invasive populations across the southern United States, Australia, China, Taiwan, and the Caribbean, causing ecological havoc and significant human health concerns. These aggressive ants deliver painful stings that produce distinctive pustules and can trigger severe allergic reactions in approximately 1% of the population, leading to anaphylaxis and potentially death if not treated promptly. Each year in the United States alone, fire ants are responsible for more than 100,000 medical consultations and several fatalities. Beyond the direct health impacts, these invasive ants displace native species, damage electrical equipment, and affect agricultural productivity, creating economic burdens estimated at $6.7 billion annually in the United States. Their remarkable adaptability—including forming waterproof rafts during floods that allow entire colonies to survive—has made control efforts particularly challenging.

Kissing Bugs: Vectors of Chagas Disease

Triatomine bugs, commonly known as “kissing bugs” due to their tendency to bite humans near the mouth, have expanded their range northward from Latin America into the southern United States, bringing with them the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi that causes Chagas disease. This chronic illness affects approximately 8 million people worldwide and can lead to severe cardiac and digestive complications decades after initial infection if left untreated. Unlike many insect vectors that transmit disease through bites, kissing bugs defecate after feeding, and the parasite enters the body when infected feces are accidentally rubbed into the bite wound or mucous membranes. Climate change is projected to expand suitable habitat for these insects by up to 50% by 2050, potentially exposing millions more people to Chagas disease in regions previously unaffected. Adding to concerns, recent research has documented increasing rates of domestic dogs becoming infected in the United States, creating additional reservoir hosts that complicate control efforts.

Asian Giant Hornets: The “Murder Hornet” Threat

The Asian giant hornet (Vespa mandarinia), sensationally dubbed the “murder hornet” by media outlets, created widespread alarm when specimens were discovered in Washington State and British Columbia in 2019 and 2020. Native to East Asia, these hornets are the world’s largest, measuring up to two inches in length, and possess potent venom that can cause severe pain, tissue necrosis, and even kidney failure in cases of multiple stings. In their native range, they kill approximately 50 people annually, primarily due to anaphylactic reactions. While eradication efforts appear to have been successful in North America, their brief presence highlighted vulnerabilities in biosecurity systems and the potential for other venomous insects to establish invasive populations. Beyond direct human health concerns, these hornets devastate honeybee colonies—capable of slaughtering an entire hive in hours—threatening pollination services essential for agriculture and human food security.

Ticks: Expanding Ranges and Emerging Diseases

Several invasive tick species have established populations outside their native ranges in recent decades, bringing with them a complex array of pathogens that cause serious human illnesses. The Asian longhorned tick (Haemaphysalis longicornis), discovered in New Jersey in 2017, has since spread to at least 17 U.S. states and is capable of transmitting several pathogens, including the virus causing severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome (SFTS), which has a 10-30% mortality rate in Asia. Meanwhile, changing climate patterns have allowed native ticks like Ixodes scapularis (the blacklegged tick) to expand their ranges northward, bringing Lyme disease, anaplasmosis, babesiosis, and Powassan virus to previously unaffected regions. Ticks present particular challenges for public health because they can simultaneously transmit multiple pathogens through a single bite, often remain attached for days while feeding, and can complete their life cycles on a wide variety of mammalian hosts, making control exceptionally difficult.

Brown Marmorated Stink Bug: An Allergenic Nuisance

The brown marmorated stink bug (Halyomorpha halys), native to East Asia, has become established across North America and Europe since its introduction in the 1990s, creating both agricultural and human health concerns. While not vectors of disease, these insects release potent defensive chemicals when threatened or crushed that can trigger respiratory distress, skin irritation, and allergic reactions in sensitive individuals. Their habit of invading homes by the thousands during autumn months as they seek overwintering sites creates significant psychological distress and quality-of-life impacts for affected households. Researchers have documented cases of occupational asthma among agricultural workers repeatedly exposed to these insects, particularly in confined spaces like packing facilities where stink bugs contaminate harvested crops. The control methods themselves—including insecticides and repellents—can pose additional health concerns when used improperly in residential settings, creating a complex public health challenge.

Africanized Honey Bees: When Beneficial Insects Turn Dangerous

Africanized honey bees, colloquially known as “killer bees,” emerged from a 1950s breeding experiment in Brazil that crossed European honey bees with African subspecies in an attempt to increase honey production in tropical climates. These hybrid bees escaped captivity in 1957 and have since spread throughout South and Central America and into the southern United States, bringing with them a defensive temperament far more aggressive than their European counterparts. When disturbed, Africanized colonies can pursue perceived threats for up to a quarter-mile, with attacks involving thousands of stings that can overwhelm even non-allergic victims through venom toxicity. Since their arrival in the U.S. in 1990, they have been responsible for approximately 1,000 documented human deaths across the Americas, disproportionately affecting outdoor workers, the elderly, and those unable to flee quickly. While they produce honey and provide pollination services like European honey bees, their defensive behavior creates significant public health concerns in affected regions.

Bed Bugs: The Global Resurgence

Bed bugs (Cimex lectularius) represent a unique case of an ancient human parasite that nearly disappeared in developed nations by the 1950s, only to make a dramatic global resurgence beginning in the 1990s due to increased international travel, changes in pest management practices, and widespread insecticide resistance. While not known to transmit disease, these persistent nocturnal feeders cause significant physical and psychological suffering through itchy welts, sleep disturbance, anxiety, and social stigma. Research has linked chronic bed bug infestations to mental health conditions including post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and even suicidal ideation in severe cases. The economic impact is equally significant—infestations in the United States alone cost an estimated $500 million annually in treatment costs, property damage, lost wages, and litigation. Recent studies have also identified concerning potential for these insects to serve as mechanical vectors for pathogens including MRSA and Trypanosoma cruzi, though transmission to humans has not yet been documented in natural settings.

German Yellowjackets: Aggressive Urban Invaders

The German yellowjacket (Vespula germanica) has established invasive populations on six continents, making it one of the world’s most successful invasive insects with significant implications for human health. Unlike many native yellowjacket species that build annual colonies, invasive populations in mild climates often develop perennial nests containing tens of thousands of individuals, dramatically increasing human encounter rates in urban and suburban environments. These wasps are attracted to human foods and garbage, frequently appearing at outdoor dining venues, picnics, and waste receptacles where they aggressively defend food resources and can sting multiple times without dying. In countries including New Zealand, Australia, and Argentina, they have become the leading cause of insect-related anaphylaxis, with mortality rates comparable to those from honeybee stings despite much lower public awareness of the risk. Their success stems partly from behavioral flexibility—invasive populations show greater scavenging behavior and protein-seeking than in their native range, leading to increased human interactions.

Public Health Response Strategies

Effective response to invasive insects affecting human health requires coordinated approaches across multiple sectors including public health, agriculture, transportation, and international trade regulation. Surveillance networks utilizing traditional trapping methods alongside newer technologies like environmental DNA sampling and citizen science reporting apps have proven critical for early detection of invasive species before they become established. The One Health approach—recognizing the interconnection between human, animal, and environmental health—has gained traction as an effective framework for addressing complex invasive species challenges. Public education campaigns focused on prevention measures, such as eliminating standing water for mosquito control or checking for ticks after outdoor activities, represent cost-effective interventions that empower communities to reduce exposure risks. Technological innovations including sterile insect techniques, gene drive systems, and biological control agents offer promising avenues for future management, though each carries ecological considerations that must be carefully evaluated.

Climate Change: Amplifying Invasion Threats

Climate change acts as a powerful multiplier of health risks from invasive insects by altering temperature and precipitation patterns that determine where these species can survive and reproduce. Models predict that warming temperatures will allow disease vectors like Aedes mosquitoes to expand into previously unsuitable regions, potentially exposing up to 1 billion additional people to dengue risk by 2080. Extended warm seasons in temperate regions are already allowing some invasive insects to produce additional generations each year, leading to larger population sizes and increased human exposure. Rising temperatures also accelerate the development rate of pathogens within insect vectors—the extrinsic incubation period—potentially increasing transmission efficiency of diseases like malaria and dengue. Perhaps most concerning, climate change may create evolutionary pressures favoring the emergence of new relationships between insects, pathogens, and humans, potentially leading to novel disease threats for which medical systems are unprepared.

Conclusion

Invasive insects represent an increasingly significant yet often underappreciated threat to global public health. As human activities continue to facilitate the movement of species across natural boundaries, and climate change creates more hospitable conditions for these invaders, we can expect both the range and impact of these species to grow. Addressing these challenges requires coordinated international action, innovative control strategies, and greater public awareness. By understanding the specific mechanisms through which these tiny invaders affect human health, we can develop more effective preventive measures and response systems. The battle against invasive insects affecting human health stands as a perfect example of how ecological disruptions can have profound consequences for human wellbeing, underscoring the fundamental interconnectedness of all living systems on our planet.