In the intricate web of our ecosystem, few creatures play as vital a role as pollinators do. Bees, butterflies, beetles, and other insects are responsible for pollinating approximately 75% of the world’s flowering plants, including many of the fruits and vegetables we consume daily. Yet, these essential creatures face unprecedented challenges – habitat loss, pesticide exposure, climate change, and disease, leading to alarming declines in pollinator populations worldwide. The good news? You don’t need to be an environmental scientist or a professional conservationist to make a meaningful difference. By creating an insect hotel in your backyard, you can provide crucial habitat for these beneficial creatures while enhancing your garden’s productivity and beauty. This article explores how these simple structures can become powerful tools in pollinator conservation, right from your own backyard.

Understanding the Pollinator Crisis

The decline of pollinator populations represents one of the most pressing environmental challenges of our time. Since the late 1990s, beekeepers have reported unusually high colony losses, with managed honey bee colonies in the United States declining by more than 40% in recent years. Native bee species face even steeper declines, with some once-common bumblebees now endangered. This crisis extends beyond bees to other pollinating insects like butterflies, moths, and beetles, many of which have seen population reductions of 45-95% depending on the species and region. The consequences of this decline reach far beyond ecological concerns, threatening global food security as approximately one-third of human food production depends directly on insect pollination. Without immediate intervention at both policy and individual levels, we risk further destabilizing these essential ecological relationships that sustain our food systems.

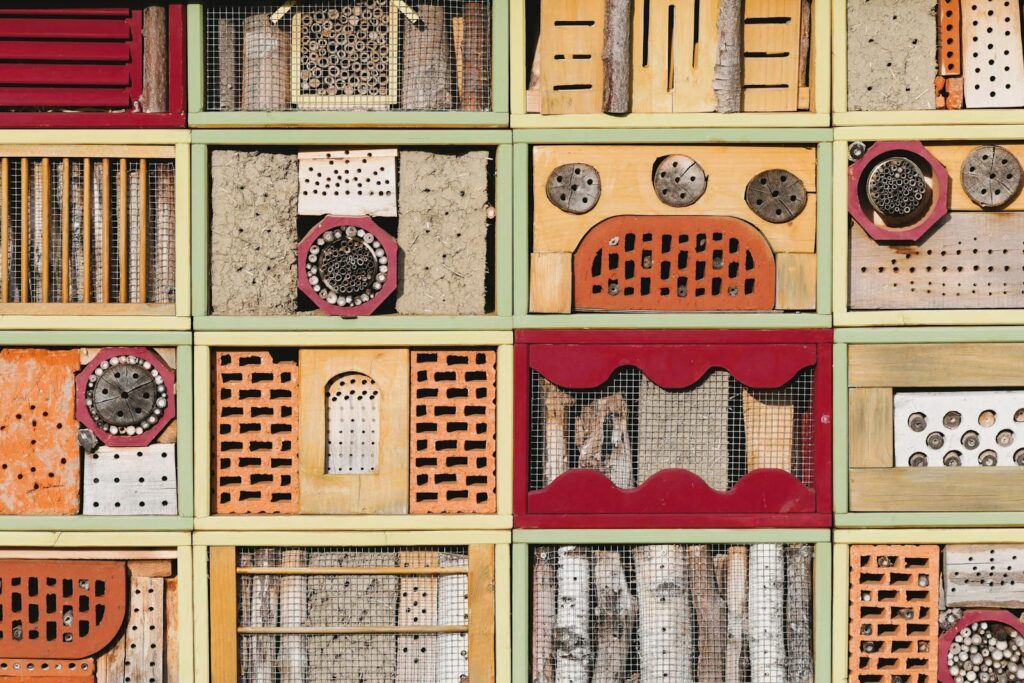

What Exactly Is an Insect Hotel?

An insect hotel is a purpose-built structure designed to provide shelter and breeding habitat for beneficial insects, particularly pollinators and natural pest controllers. Unlike the uniform hives used for honey bee colonies, insect hotels cater to solitary bees, lacewings, ladybugs, and numerous other species that don’t live in collective hives but still require protected spaces for nesting and overwintering. These structures typically consist of various compartments filled with natural materials like hollow stems, drilled wood blocks, pine cones, and rolled cardboard that mimic the diverse nesting preferences of different insect species. The design can range from simple DIY projects using repurposed materials to elaborate multi-chamber constructions resembling whimsical miniature buildings. Regardless of complexity, each hotel serves as critical habitat infrastructure in landscapes where natural nesting sites have been reduced or eliminated through urbanization and intensive agriculture.

Why Pollinators Need Our Help

Pollinators face multiple interconnected threats that have dramatically accelerated their decline in recent decades. Habitat fragmentation and loss stand as primary challenges, as urban development, industrial agriculture, and monoculture farming have eliminated the diverse flowering landscapes that once provided food and shelter for these creatures. Chemical pressures compound these problems, with neonicotinoids and other pesticides disrupting insects’ nervous systems, impairing their navigation abilities, and reducing their reproductive success even at sublethal doses. Climate change introduces additional stressors by altering flowering times that pollinators have evolved alongside for millennia, creating dangerous mismatches between when insects emerge and when their food sources bloom. The spread of diseases, particularly in bee populations, has accelerated due to globalized beekeeping practices that facilitate pathogen transmission across continents. These combined pressures have created a perfect storm threatening pollinator survival, making human intervention through habitat creation increasingly essential for their conservation.

Benefits of Insect Hotels Beyond Pollination

While pollination support represents the primary ecological function of insect hotels, these structures deliver multiple additional benefits to both gardens and broader ecosystems. Many hotel residents, including lacewings, parasitic wasps, and ladybugs, serve as natural pest controllers, reducing or eliminating the need for chemical pesticides by consuming aphids, mites, and other garden pests. This biological pest management creates healthier plant communities while preserving beneficial insect populations. Insect hotels also function as valuable educational tools, offering observable wildlife interactions that can transform gardens into living classrooms for children and adults alike. The visible insect activity provides opportunities to witness life cycles, behavioral patterns, and ecological relationships firsthand. Furthermore, these structures enhance local biodiversity by supporting specialist species that might otherwise disappear from urban and suburban landscapes, contributing to more resilient ecosystem functioning through increased species richness and ecological redundancy.

Choosing the Right Location for Your Insect Hotel

Strategic placement significantly influences an insect hotel’s effectiveness as pollinator habitat. Most beneficial insects require consistent warmth and protection from extreme elements, making south or southeast-facing locations ideal for maximizing sunlight exposure without overheating during summer afternoons. The structure should be positioned at least 3-4 feet above ground level to prevent soil moisture from causing premature decomposition while keeping the hotel safe from ground-dwelling predators. Wind protection proves equally important, as strong gusts can deter insects from approaching or nesting; placing hotels against walls, fences, or within partially sheltered garden areas creates ideal microclimate conditions. Proximity to diverse flowering plants represents another critical factor, as most hotel inhabitants need nectar and pollen sources within 300-500 feet of their nesting sites. The location should remain undisturbed throughout the year, as frequent movement disrupts life cycles and may cause inhabitants to abandon the hotel entirely.

Essential Materials for Building Effective Insect Housing

Creating an effective insect hotel requires thoughtful material selection to accommodate diverse nesting preferences while ensuring durability and safety. The outer structure typically consists of untreated wood frames, as chemical treatments can harm insects and potentially contaminate pollen and nectar. Cedar, oak, or other naturally rot-resistant woods offer the best longevity in outdoor conditions without requiring chemical preservatives. Filling materials should incorporate various natural elements including hollow plant stems (bamboo, reeds, or perennial stalks) cut to 4-8 inch lengths for mason and leafcutter bees; drilled hardwood blocks with holes ranging from 2-10mm in diameter for different bee species; pinecones, bark, and small branches for beetles and some wasps; and loose materials like straw, dried leaves, or corrugated cardboard for lacewings and certain soil-nesting insects. A protective roof covered with waterproof materials such as cedar shingles or metal sheeting prevents excessive moisture from degrading the structure while extending its functional lifespan.

DIY Insect Hotel Designs for Beginners

For newcomers to insect habitat creation, several straightforward designs offer excellent starting points without requiring specialized woodworking skills. The simplest approach involves bundling 15-20 hollow stems like bamboo or reed sections, securing them with garden twine, and placing them horizontally in a sheltered location at least three feet above ground. Another beginner-friendly option utilizes a small wooden box or repurposed container filled with rolled cardboard tubes and hollow stems of varying diameters to attract different species. Drilled block hotels represent another accessible option, created by drilling holes of various diameters (between 2-10mm) into untreated hardwood blocks to a depth of about 6 inches, making sure not to drill completely through. More ambitious beginners might construct a simple frame hotel by building a wooden shadow box with an open front, partitioning it into sections, and filling each compartment with different nesting materials. These entry-level designs can be completed in an afternoon with basic tools while still providing valuable habitat for multiple pollinator species.

Advanced Hotel Designs for Experienced Builders

For those with woodworking experience seeking to create more elaborate and comprehensive insect habitats, several advanced designs offer enhanced ecological functionality and aesthetic appeal. Multi-tier hotels incorporate a structured frame with numerous compartments specifically tailored to different insect groups, including specialized sections for ground-nesting bees (filled with clay-sand mixtures), butterfly hibernation chambers (with vertical bark slices), and overwintering sections for ladybugs and lacewings (packed with pine cones and straw). Some advanced builders incorporate green roofs planted with drought-resistant sedum varieties, creating additional foraging opportunities while improving the structure’s thermal insulation properties. Specialized bee condo systems feature replaceable nesting tubes with observation windows that allow monitoring of cell development without disturbing the inhabitants. The most ambitious designs integrate water features like small clay saucers with landing stones that provide safe drinking stations during dry periods, alongside attached planting areas with early-season pollen sources like crocus or winter heath that support pollinators emerging before most garden flowers bloom.

Specific Features for Different Pollinator Species

Different pollinator species require specialized habitat features to successfully utilize insect hotels for reproduction and shelter. Mason bees prefer tubes or holes between 6-8mm in diameter with smooth interiors and closed backs, positioned horizontally in sunny locations. Leafcutter bees select slightly smaller cavities between 4-6mm, while smaller native bee species utilize holes as tiny as 2-3mm in diameter. Carpenter bees, conversely, benefit from softer wood blocks they can excavate themselves, though this may require replacement every few seasons as the wood deteriorates. Lacewings prefer narrow crevices filled with straw or wood shavings, positioned in partial shade rather than full sun. Ladybugs congregate in hibernation chambers filled with pine cones, bark pieces, and dried leaves, particularly in structures placed near aphid-prone plants they patrol during active seasons. Certain butterfly species utilize vertical bark sections with narrow spaces for chrysalis attachment during metamorphosis, while others seek sheltered, dry compartments for overwintering as adults. By incorporating these species-specific elements, hotel designers can maximize biodiversity benefits while supporting specialized ecological niches.

Companion Planting to Enhance Insect Hotel Success

The effectiveness of an insect hotel depends significantly on surrounding plant communities that provide essential food resources throughout the growing season. Strategic companion planting transforms a simple hotel into a comprehensive pollinator habitat system. Early-season bloomers like crocus, snowdrops, and winter heath provide critical first food sources for emerging pollinators when few other flowers are available. Mid-season flowering natives like coneflower (Echinacea), bee balm (Monarda), and black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia) sustain diverse bee and butterfly populations during peak activity periods. Late-season bloomers including asters, goldenrod, and sedum extend foraging opportunities into autumn when many insects prepare for overwintering. Including plants with different flower shapes accommodates varying tongue lengths and feeding adaptations – shallow, open flowers for short-tongued insects and tubular blooms for long-tongued species like bumble bees and butterflies. Native plants typically outperform non-natives in supporting local pollinator populations, often providing 4-100 times more ecological value through better nectar quality, appropriate pollen protein content, and synchronized bloom times evolved alongside native insects.

Maintenance and Care of Your Insect Hotel

Proper maintenance ensures the long-term effectiveness and safety of insect hotels as pollinator habitat. Annual autumn cleaning represents a crucial maintenance task, focusing on removing and replacing badly weathered or moldy materials while leaving occupied sections undisturbed until spring emergence. Gentle brushing of hotel exteriors removes spider webs that might trap beneficial insects, though complete elimination of spiders isn’t necessary as they contribute to garden pest control. Spring monitoring allows tracking which hotel sections receive the most use, guiding future design improvements based on observed preferences. Periodic checks throughout the growing season help identify potential problems like parasitic wasp infestations or water damage requiring intervention. After 2-3 years, complete replacement of nesting materials prevents disease buildup that can occur when the same nesting sites are reused repeatedly. Protective winter measures in harsh climates might include attaching breathable fabric covers during extreme weather while ensuring the structure remains firmly anchored against winter storms. This maintenance calendar ensures the hotel remains a safe, healthy habitat rather than becoming an ecological trap where parasites or diseases concentrate.

Common Mistakes to Avoid with Insect Hotels

Several common mistakes can significantly reduce an insect hotel’s effectiveness or even transform it from a pollinator habitat into an ecological liability. Using materials treated with pesticides, preservatives, or chemicals represents the most dangerous error, as these substances can poison hotel inhabitants or contaminate pollen provisions stored for developing larvae. Drilling holes all the way through wooden blocks creates problematic wind tunnels that most cavity-nesting bees actively avoid, while using bamboo with nodes/dividers intact prevents insects from accessing the full tube depth they require. Rough-cut or splintered hole entrances damage delicate insect wings and deter nesting completely, necessitating careful sanding of all openings. Positioning hotels in deep shade practically guarantees abandonment, as most pollinating insects require warmth for proper development. Inadequate rain protection leads to mold and fungal growth that can kill developing larvae, while insufficient anchoring allows destructive movement during storms. Perhaps most problematic is the “build and forget” approach that neglects maintenance, potentially creating breeding grounds for parasites, mites, and diseases that spread to wild populations. Awareness of these pitfalls allows builders to create truly beneficial structures rather than attractive but ecologically dysfunctional garden decorations.

Observing and Learning from Your Insect Hotel

Insect hotels offer remarkable opportunities for ecological observation and citizen science participation beyond their conservation value. Keeping a hotel journal to document first occupants, seasonal patterns, and species diversity provides valuable data while deepening personal connection to local wildlife. Photography of visiting insects aids identification while creating fascinating time-lapse documentation of hotel colonization, with comparison photographs taken at regular intervals revealing population fluctuations and habitat preferences. Observation periods scheduled during peak activity times (typically warm, sunny mornings) allow monitoring of behaviors like pollen collection, predator-prey interactions, and nesting activities. Sharing observations through citizen science platforms like iNaturalist or Bumble Bee Watch contributes to broader scientific understanding of pollinator distribution and population health. For families with children, insect hotels become powerful environmental education tools, offering direct experience with concepts like metamorphosis, ecological relationships, and biodiversity that traditional classroom instruction can’t match. Through careful observation, hotel builders transform from passive wildlife observers to active participants in both conservation and scientific discovery.

Connecting with Broader Conservation Efforts

Individual insect hotels gain amplified conservation impact when connected to larger pollinator protection initiatives. Community-level coordination can create pollinator corridors linking isolated habitat patches, allowing genetic exchange between otherwise isolated populations while facilitating seasonal migrations. Local garden clubs and conservation organizations frequently offer certification programs that recognize pollinator-friendly properties, providing both guidance for improvement and community recognition for conservation efforts. Many municipalities now sponsor public insect hotel installations in parks and community gardens, creating opportunities for habitat expansion through volunteer participation. Scientific research partnerships between citizen scientists and academic institutions increasingly utilize data from backyard insect hotels to track population trends and habitat utilization across broad geographic areas. Policy advocacy represents another connection point, as documented pollinator activity from private gardens strengthens arguments for reducing pesticide use, preserving greenspace, and implementing pollinator-friendly municipal landscaping practices. By viewing backyard insect hotels as components of a larger conservation network rather than isolated projects, builders maximize their contribution to reversing pollinator decline while connecting with like-minded advocates across communities.

The Future of Insect Conservation in Urban Spaces

The humble insect hotel represents just the beginning of an emerging urban conservation approach that reimagines human-dominated landscapes as potential wildlife habitats. Forward-thinking cities now incorporate pollinator protection into urban planning, creating comprehensive pollinator pathways through neighborhoods with strategically placed habitat features, including insect hotels, native plant installations, and pesticide-free maintenance policies. Architectural innovation increasingly integrates insect habitat directly into building designs, with bee brick façades, green roofs, and habitat walls transforming urban structures from ecological barriers into biodiversity support systems. Community science programs centered around insect hotel monitoring generate valuable population data while building public engagement with conservation issues previously considered relevant only to rural or natural areas. Educational institutions from elementary schools to universities now utilize insect hotels as living laboratories, connecting theoretical ecology with observable wildlife interactions within school grounds. This shift toward viewing urban spaces as potential conservation zones rather than ecological write-offs represents a profound paradigm change with tremendous implications for biodiversity protection in an increasingly urbanized world. By participating in this movement through backyard insect hotels, individual gardeners contribute to a fundamental reimagining of the relationship between human habitation and wildlife conservation.

Conclusion

As pollinator populations continue to face unprecedented challenges, insect hotels represent a practical, accessible way for individuals to contribute meaningful conservation impact. These simple structures, when properly designed and maintained, provide crucial habitat for the creatures that sustain our food systems and natural ecosystems. Beyond their ecological benefits, they create opportunities for people to reconnect with the natural processes happening just outside their homes. Building one doesn’t require complex tools or expert knowledge—just thoughtful placement, suitable materials, and a commitment to pesticide-free care. Over time, you may notice increased activity in your garden, healthier plants, and a deeper awareness of the balance between human spaces and insect life. As more people participate, fragmented habitats begin to link, creating broader support systems for pollinators under stress. Insect hotels won’t fix every problem pollinators face, but they offer a direct, tangible way to take action right now.